By Dr. Akash Mazumder

Abstract:

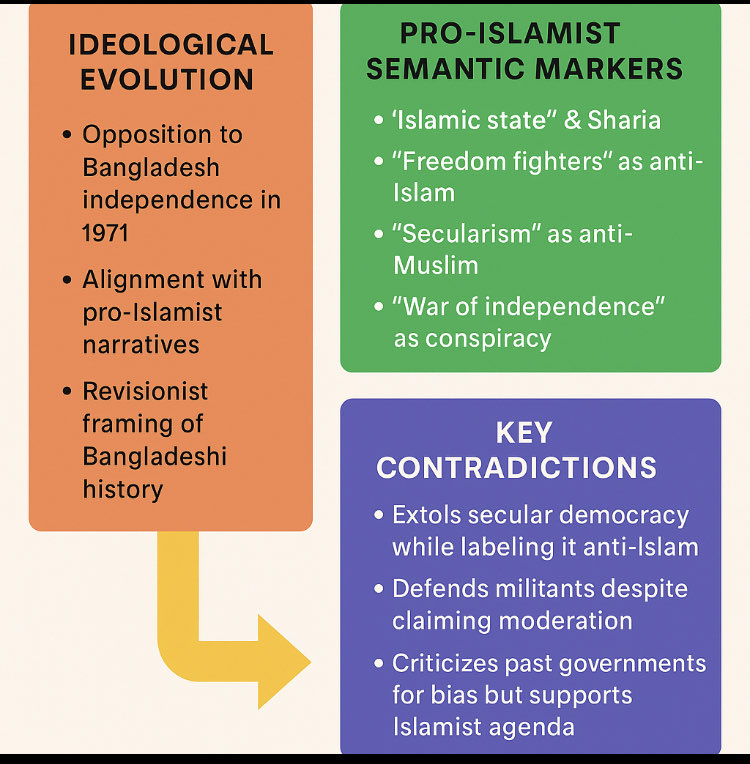

This academic research article critically investigates the works and ideological positioning of Dr. Ali Riaz, an American citizen and writer of Bangladeshi origin, who has consistently projected narratives that align with radical Islamic ideologies and pro-Pakistan sentiments. Despite his reputation in academic and media circles, Riaz’s persistent opposition to the historical truth of Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971 and his advocacy for Islamic political parties that opposed the birth of the nation raise critical ethical and scholarly concerns.

Through detailed textual analysis of his publications, interviews, and public engagements, this article aims to demonstrate how Dr. Riaz promotes revisionist narratives that favor the Islamist communal agenda while undermining the foundational secular and democratic principles of Bangladesh, including its 1972 Constitution. The paper situates Riaz’s ideological orientation within the broader context of radical Islamist propaganda, revealing how his scholarship is leveraged by vested interests—including the current undemocratic regime in Bangladesh—to distort the country’s liberation history and support radical Islamist and communal transformations.

Keywords: Ali Riaz, Radical Islamism, 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, Islamist Politics, Bangladesh Awami League, Constitution of 1972, Disinformation, Pro-Pakistan Narrative

1. Introduction

Dr. Ali Riaz, a political analyst and academic with visibility in South Asian studies, has emerged as a polarizing figure in contemporary discourse on Bangladesh. While his credentials and affiliations lend him academic credibility, a close review of his published texts, media commentaries, and public engagements reveals a consistent ideological alignment with radical Islamic politics and an apparent hostility toward the independence movement of Bangladesh in 1971. This introduction sets the groundwork for a comprehensive critical analysis of Riaz’s writings and public discourse, questioning the scholarly integrity and political motivations behind his framing of history, politics, and society in Bangladesh.

The economy of fundamentalism in Bangladesh: Funding, revenue, and political patronage

Now the whole Bangladesh is under life support

Understanding the Yunus–Pakistan nexus

Riaz’s early career began within a post-colonial context where the ideological fault lines in South Asia were heavily influenced by Cold War geopolitics and the remnants of Islamic nationalism propagated by Pakistan’s military and political establishment. His works display a noticeable sympathy toward Jamaat-e-Islami, a party that actively opposed Bangladesh’s independence and collaborated with the Pakistan Army during the Liberation War. His framing of the party as a legitimate political stakeholder in democratic Bangladesh disregards its violent legacy, its convictions in war crimes tribunals, and its rejection of the secular values enshrined in the Constitution of 1972.

Moreover, Dr. Riaz’s criticisms of the Bangladesh Awami League (AL), Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and the Freedom Fighters often exceed academic critique and veer into ideological delegitimization. His writings lack adequate engagement with primary sources from 1971, overlook established historical scholarship, and appear more focused on rehabilitating the image of pro-Pakistani Islamists within Bangladesh’s political mainstream.

The introduction proceeds with a methodological overview, detailing the qualitative textual analysis of Dr. Riaz’s major publications, including Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh (2008), God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh (2010), and multiple op-eds published in international outlets such as The Diplomat, Al Jazeera, and The Daily Star. Interviews, conference proceedings, and social media interactions were also surveyed to identify rhetorical patterns that align with radical Islamic worldviews and strategic geopolitical narratives sympathetic to post-1971 Pakistani nationalism.

This investigation poses the following critical questions:

-How does Dr. Riaz frame the history and politics of Bangladesh vis-à-vis the 1971 Liberation War?

-What are the ideological underpinnings of his consistent criticism of secular nationalist forces and leaders?

-To what extent do his works function as soft propaganda for Islamist parties like Jamaat-e-Islami?

-How has Dr. Riaz influenced foreign and domestic policy discourse around Bangladesh’s democratic and constitutional identity?

To answer these, the article proceeds in three key sections: (1) His Stand Against Independent Bangladesh, (2) His Writings Against 1971, AL, and Freedom Fighters, and (3) His Alignment with Radical Islamism as a Scholar.

The ideological contradictions in Riaz’s writings expose the troubling convergence of academic respectability with radical communal propaganda. This paper aims to unpack the consequences of allowing such narratives to influence national and international discourses on Bangladesh.

1: Ali Riaz Stands Against Independent Bangladesh

Dr. Ali Riaz’s positioning on the 1971 Liberation War has consistently undermined the foundational narrative of Bangladesh’s birth. While many academics and historians globally recognize the Liberation War as a just struggle against Pakistani military oppression, Riaz’s writings tend to minimize the genocidal nature of the conflict and question the legitimacy of the Awami League’s leadership in that struggle. This section aims to unpack his narrative framework by closely examining his portrayal of the war, the actors involved, and the aftermath.

Jihadi infiltration in Bangladesh Army: Recent controversial activities

‘I am a militant’ slogan chanted, al-Qaeda flags displayed again in Dhaka

Bangladeshi militants reach to Malaysia to promote jihad at home

A recurring theme in Riaz’s scholarship is the attempt to reframe 1971 not as a liberation struggle rooted in linguistic and political self-determination, but as a geopolitical maneuver exploited by India and regional actors. In doing so, Riaz subtly revives the discredited Pakistani narrative that accuses India of fabricating the genocide narrative to dismember Pakistan. This deliberate distortion aligns his academic posture with a form of ideological revisionism that ultimately serves the interests of pro-Pakistan Islamists in Bangladesh.

In his commentary and books, Riaz frequently expresses skepticism toward the authenticity of documented genocide accounts, downplaying the mass killings of civilians and the role of Jamaat-e-Islami and other collaborators. His reluctance to accept the internationally recognized figure of three million martyrs or the sexual violence committed by the Pakistani Army and its allies is not merely academic caution—it is a politicized stance that diminishes the historical trauma experienced by the Bengali population.

Riaz’s antagonism toward the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh also warrants attention. He has consistently critiqued the document’s secular orientation, describing it as overly rigid and hostile to religious freedoms. However, this criticism functions as a veiled argument for reintroducing communal and Islamic elements into national governance. Such a position mirrors the demands of the very Islamist parties that opposed independence in 1971. By calling for a ‘reform’ of the Constitution, Riaz indirectly validates the anti-secular agenda advanced by post-1975 military regimes and the Jamaat-e-Islami revivalist wave of the 1990s.

Another critical aspect of his anti-independence stance is his portrayal of the Bangladesh Army’s role in post-independence politics. While legitimate critiques exist about the military’s authoritarian interventions, Riaz draws moral equivalence between the Mujib regime’s post-war difficulties and the mass atrocities of 1971. This ‘both-sides-ism’ delegitimizes the moral clarity of the liberation cause and exonerates the pro-Pakistani actors who continue to deny their role in genocide and war crimes.

Riaz also deploys selective language in framing national movements. While terms like ‘civil war,’ ‘ethnic tensions,’ or ‘regional uprising’ appear in his descriptions of 1971, he avoids using ‘genocide,’ ‘occupation,’ or ‘collaborator’—terms essential to understanding the Liberation War’s moral and legal framework. His avoidance of this terminology signals a broader ideological discomfort with accepting the historical consensus surrounding Bangladesh’s independence.

Furthermore, Riaz’s criticism of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) is not centered on legal standards or procedural fairness but framed as a political vendetta by the ruling Awami League. He fails to acknowledge that the ICT was established in response to decades of demands for justice by survivors and human rights advocates. His writings ignore the detailed legal proceedings, confessions, and evidence-based convictions of war criminals. Instead, he frames the process as an authoritarian project meant to suppress political opposition—thus shielding the legacy of Islamist actors involved in 1971.

Through public appearances and op-eds, Riaz often invokes the trope of “secular authoritarianism” to describe post-2009 Bangladesh. This terminology falsely equates the AL government’s democratic mandate and attempts to preserve secularism with the repressive tactics of Islamist regimes. It creates a distorted binary in which radical Islamists appear as victims of state oppression while secular leaders are framed as authoritarian. This discursive inversion aligns with the strategy of Islamist parties that seek international sympathy while continuing to subvert democratic and secular institutions from within.

In summary, Dr. Ali Riaz’s narrative positioning on Bangladesh’s independence is not merely an academic deviation but an ideological alignment with forces historically opposed to the nation’s sovereignty. His persistent attempts to dilute the moral legitimacy of 1971, his indirect advocacy for the reintroduction of communal politics, and his strategic framing of secular governance as repressive reveal a coherent pattern of anti-liberation bias. This section offers foundational insight into how scholarly discourse can be weaponized to legitimize historical revisionism and political subversion.

2: His Writings, using patterns of languages Against 1971, Awami League, Freedom Fighters, and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Dr. Ali Riaz’s body of work frequently employs revisionist techniques and ideological distortions that target key historical and political figures involved in the Liberation War of Bangladesh. His writings not only express implicit sympathies toward anti-independence forces but also systematically attempt to delegitimize the historical role of the Awami League, the Freedom Fighters, and the country’s founding father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Through linguistic manipulation, selective historiography, and strategic omissions, Riaz reconstructs a narrative that displaces the moral and political authority of the liberation movement and elevates the position of radical and communal opposition figures.

3. Revisionist Framing of 1971 and Role of Awami League

One of Riaz’s key rhetorical strategies is to challenge the moral and political legitimacy of the Awami League’s leadership during 1971. In his book Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh (2008), Riaz downplays the systematic extermination and rape carried out by the Pakistani military and its local collaborators, while suggesting that the political crisis of 1971 was largely a result of mismanagement and authoritarianism by the Awami League. This false equivalence ignores historical evidence that Pakistan’s military establishment had no intention of honoring the electoral victory of AL in the 1970 elections.

By framing the AL’s leadership as ‘opportunistic’ or ‘sectarian,’ Riaz attempts to dilute their central role in uniting East Pakistanis behind the independence movement. His interpretations consistently echo the narratives of pro-Pakistani commentators who argue that the war was not a just liberation but a consequence of regional breakdown exacerbated by Indian interference. The framing minimizes the popular support for Mujib’s Six-Point Movement, casting doubt on its mass appeal and implying that the demand for autonomy was orchestrated by political elites rather than demanded by the masses.

4. Demonization of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Riaz’s treatment of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is marked by subtle denigration and rhetorical deflation. He often refers to Mujib as ‘controversial’ or ‘authoritarian,’ focusing disproportionately on the post-independence governance challenges rather than on Mujib’s historic role in uniting the Bengali people and leading them to independence. In numerous articles, including his contributions to The Daily Star and The Diplomat, Riaz critiques Mujib’s introduction of the one-party BAKSAL system without providing the geopolitical context of post-war reconstruction and global Cold War pressures.

More problematically, Riaz’s critique of Mujib ignores the structural sabotage carried out by anti-liberation forces and international conspiracies that culminated in Mujib’s assassination in 1975. By omitting references to the deep state and foreign alignments behind the coup, Riaz constructs an image of Mujib as a failed leader whose death was politically inevitable. This line of thinking aligns disturbingly with the narratives of Mujib’s assassins and the forces that rolled back the secular progress of Bangladesh in the subsequent decades.

5. Vilification of the Freedom Fighters and the Spirit of Liberation

In contrast to the valorization of the Jamaat-e-Islami and other communal parties as legitimate political actors, Riaz treats Freedom Fighters and Muktijoddhas as either politicized agents of the ruling party or relics of a mythologized past. In his various writings, he questions the institutionalization of their memory in public policies, such as state pensions, quotas, and commemorations. He portrays these initiatives as partisan tools rather than national symbols of resistance against genocide.

Riaz’s language choices further betray this bias. For instance, while he uses sanitized and abstract language to describe the Razakars and Al-Badr, he deploys terms like ‘government-backed vigilantes’ or ‘paramilitaries’ to describe post-1971 security units composed of former freedom fighters. This deliberate inversion of moral terminology aligns with the rhetorical strategies of post-1975 military regimes that sought to erase the moral supremacy of the Liberation War.

6. Strategic Omission and Intellectual Whitewashing of Jamaat-e-Islami

Perhaps the most glaring aspect of Riaz’s writing is his persistent attempt to normalize Jamaat-e-Islami as a democratic stakeholder. He downplays their genocidal role in 1971 and glosses over the well-documented activities of war criminals like Ghulam Azam, Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, and Motiur Rahman Nizami. While Bangladeshi courts and international observers have acknowledged the involvement of Jamaat in war crimes, Riaz continues to present them as misunderstood political victims.

This strategic omission is evident in his framing of the International Crimes Tribunal as a “political trial” rather than a long-overdue mechanism of transitional justice. His critiques of the ICT rely heavily on international procedural standards while neglecting the socio-political necessity of reckoning with mass atrocities. In this way, Riaz delegitimizes justice efforts, reinforcing the talking points of those who seek to erase 1971 from collective memory.

7. His Alignment with International Media Narratives Against Secular Nationalism

Riaz has effectively embedded himself in international media ecosystems that favor narratives of victimized Islamists and authoritarian secularism. In Al Jazeera, Riaz’s commentary presents a Bangladesh allegedly in decline due to “secular excesses,” “repression of dissent,” and “curtailment of religious expression.” These terms echo the vocabulary of soft-Islamist propaganda, particularly from networks funded by Qatar, Turkey, and Pakistan.

Moreover, his op-eds rarely mention the targeted assassinations of secular bloggers, the Hefazat-e-Islam attacks, or communal violence against religious minorities. This glaring omission illustrates a deliberate agenda: to shift the discourse away from radical Islamist violence and focus attention on perceived overreach by secular democratic actors. His work is therefore not a neutral academic contribution but a politicized intervention aligned with Islamist revisionism.

8. Undermining of Secularism and Constitutional Principles

Riaz’s critique of the 1972 Constitution follows a similar revisionist pattern. He argues that its secular provisions were “imposed” and “elitist,” ignoring the fact that they were the product of a national consensus forged in blood. His calls for “inclusive constitutionalism” resonate more with demands for the inclusion of Sharia elements and communal political participation rather than broader democratic representation.

He describes the secularism clause as a “source of polarization,” conveniently sidestepping the violence and exclusion perpetrated by those who opposed it. His preference for religious pluralism as defined by Islamist actors suggests that his notion of inclusivity is skewed toward communal accommodation rather than secular equality. This ideological stance directly opposes the principles for which millions died in 1971.

9. Ali Riaz and A Narrative of Delegitimization

Ali Riaz’s writings systematically delegitimize the historical, political, and moral foundations of the Bangladeshi nation-state. By questioning the legitimacy of the Awami League, tarnishing the legacy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, vilifying Freedom Fighters, and glorifying anti-liberation forces, he promotes a counter-historical narrative. His strategic language, selective omissions, and ideological affiliations place him squarely within the intellectual ecosystem that enables radical Islamic and pro-Pakistan forces to gain soft power in domestic and international forums.

Rather than engaging in objective scholarship, Riaz acts as a cultural intermediary for those who aim to rewrite Bangladesh’s liberation history through the lens of Islamist exceptionalism and communal politics. As such, his work represents not only an academic controversy but a national threat to the collective memory and future identity of Bangladesh.

10. Ali Riaz as a Radical Islamic Extremist Writer

Dr. Ali Riaz’s trajectory as an academic, political analyst, and media commentator has positioned him as a powerful voice in South Asian affairs. However, a close, critical analysis of his writings and ideological patterns reveals a troubling undercurrent of alignment with radical Islamic discourses. This section aims to deconstruct the subtle, yet ideologically charged language, themes, and positions that place Riaz’s works in proximity with the ideological orientations of radical Islamist extremism. While his rhetoric is cloaked in academic objectivity, his recurrent support for Islamist narratives, dismissal of secular ideologies, and rhetorical normalization of communalism form a coherent extremist intellectual framework that requires urgent scholarly interrogation.

11. Ideological Framework and Alignment with Radical Islamist Discourse

Riaz’s scholarship repeatedly echoes themes central to radical Islamic ideology: the opposition to secularism, promotion of Islamic identity politics, reinterpretation of national history through an Islamic lens, and delegitimization of Western and secular democratic values. These themes, while nuanced, emerge forcefully across his texts such as God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh (2010), where he presents Islamist movements as organic responses to social grievances rather than as ideologically driven groups with histories of violence and anti-democratic conduct.

His writings often adopt the Islamist claim that secularism is “anti-Islamic,” framing it as a Western import incompatible with Muslim societies. This argument undercuts the indigenous secular traditions of South Asia, including the Bengal Renaissance, and suggests that the Bangladeshi state’s efforts to maintain a secular identity are inherently oppressive. Such framing aligns with the doctrinal stance of radical Islamists who seek to dismantle constitutional secularism and replace it with Sharia-based governance systems (Nasr, 2001).

Moreover, Riaz’s ideological proximity to soft-Salafism—marked by its rejection of syncretic Islam, disdain for non-Islamic historical narratives, and defense of Islamist political parties—reflects the intellectual ecosystem that enables radicalism. While he does not endorse violence directly, his sympathetic treatment of ideologies rooted in Wahhabism and Deobandism represents an endorsement of the foundational narratives that feed into jihadist propaganda (Roy, 2004).

12. Normalization of Islamist Militancy as Political Expression

In Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh: A Complex Web (2008), Riaz presents groups such as Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HuJI-B) as socio-political products of economic deprivation and political marginalization. While structural analyses are valuable, Riaz conspicuously avoids moral and ideological critique of these groups’ extremism. His representation of their militancy as rational or inevitable minimizes their crimes, which include bombings, assassinations, and the murder of secular intellectuals (Riaz, 2008).

This analytical framing positions jihadist violence not as ideological extremism but as socio-political protest, a discourse frequently invoked by apologists of Islamic radicalism. By not emphasizing the theological indoctrination, foreign funding, or transnational jihadist linkages of these organizations, Riaz obscures the global Islamist networks influencing Bangladeshi radicalism. The deliberate depoliticization of terrorism allows him to situate Islamic militancy within a developmental narrative rather than an ideological threat (Stern, 2003).

13. Obfuscation of Global Jihadist Trends and Silence on Islamist Terrorism Abroad

Riaz’s works consistently avoid engaging with the global matrix of Islamic extremism. In a post-9/11 world, where jihadist networks like Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and Taliban are reshaping geopolitics, Riaz maintains an intellectual silence or ambiguous critique. His essays rarely acknowledge the theological doctrines—such as takfirism and martyrdom ideology—that drive radicalization. This silence is significant given that Bangladesh has been targeted by transnational jihadist groups and has seen attempts to radicalize its youth via social media and encrypted platforms (Moghadam, 2006).

In his commentary on regional security, Riaz downplays the impact of Taliban resurgence in South Asia, omits mention of ISIS cells uncovered in Bangladesh, and refrains from discussing the ideological connections between Hefazat-e-Islam and global Wahhabi agendas. Such omissions create a vacuum that distorts the scale and severity of Islamist ideological infiltration in Bangladeshi society.

14. Intellectual Defense of Jamaat-e-Islami and Its Affiliates

A central theme in Riaz’s writings is his consistent intellectual rehabilitation of Jamaat-e-Islami. He presents Jamaat not as a party with genocidal culpability but as an “excluded political actor.” This line of argumentation mirrors the rhetoric of Jamaat itself, which frames its violent past as political history rather than criminal atrocity. Riaz’s works never fully confront the war crimes committed by Jamaat leaders in 1971, including mass murder, rape, and collaboration with the Pakistan Army (Bergen, 2001).

Instead, he criticizes the banning of Jamaat as a “democratic regression,” suggesting that pluralism must include groups that have never renounced violence or apologized for war crimes. His position indirectly supports the Islamist claim that secular state policies are repressive and exclusionary, further fueling the grievance narratives that radical groups use to recruit sympathizers.

15. Use of Islamist Rhetoric in Media Engagements

In his media commentaries, especially on platforms like Al Jazeera and TRT World, Riaz adopts language typically used by Islamist propagandists. Terms like “Islamophobia,” “secular authoritarianism,” and “suppression of Islamic identity” appear frequently in his critiques of Bangladesh’s current policies. While these terms have legitimate applications, Riaz uses them selectively, often to shield Islamist actors from scrutiny.

He frames mass arrests of radical clerics, restrictions on madrasa funding, and de-platforming of hate preachers as state overreach rather than necessary counterterrorism measures. This discursive strategy aligns him with international Islamist soft-power networks seeking to rebrand Islamist actors as defenders of civil liberties rather than propagators of hate and violence (Ayoob, 2008).

16. Strategic Association with Anti-Secular Institutions and Individuals

Riaz’s academic collaborations, speaking engagements, and citations often involve institutions with ties to Islamist agendas. He has participated in seminars hosted by organizations aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood, attended forums where Jamaat leaders were honored, and published in journals sympathetic to Islamic revivalist ideologies. These associations not only bolster his visibility in Islamist circles but also serve to mainstream extremist viewpoints under the guise of scholarly dissent.

His reluctance to denounce known Islamist ideologues or critique their ideological texts further reflects his ideological affinity. Unlike scholars who critically analyze foundational texts of political Islamism (e.g., Maududi’s Towards Understanding Islam or Qutb’s Milestones), Riaz avoids textual exegesis, thereby shielding radical narratives from intellectual challenge (Kepel, 2002).

17. Delegitimization of Counterterrorism and Deradicalization Programs

Riaz regularly critiques Bangladesh’s counterterrorism measures, labeling them “authoritarian,” “opaque,” or “politically motivated.” While critique is necessary, his analyses almost entirely omit the successes of such initiatives, including the prevention of ISIS-inspired attacks, dismantling of JMB sleeper cells, and community-based deradicalization programs. He frequently portrays state interventions as acts of political suppression rather than national security imperatives.

By doing so, he contributes to the narrative—commonly echoed by radical preachers—that counterterrorism is a Western or anti-Islamic conspiracy. This undermines national resilience against extremism and creates distrust in legitimate state mechanisms aimed at protecting secular constitutionalism.

18. Intellectual Contribution to Radical Communal Constitutionalism

Perhaps most dangerously, Riaz has contributed to discourses that advocate for the erosion of the secular Constitution of 1972. His support for “inclusive constitutional reform” thinly veils a call for communal accommodation that would enshrine Islamist ideology in the state apparatus. He presents this argument under the guise of “religious freedom” and “political pluralism,” ignoring the empirical reality that communalism in South Asia has historically led to partition, pogroms, and authoritarianism.

Riaz’s ideal state is not one where religion is private and the state is neutral, but one where religious ideologies actively shape laws, policies, and education. Such a vision aligns with the political philosophy of Islamist movements that seek to Islamize the public sphere through legislation, social engineering, and identity politics (Esposito, 1999).

Conclusion: The Scholar as an Ideological Conduit of Radicalism

Dr. Ali Riaz’s ideological trajectory and academic production reveal a consistent pattern of alignment with radical Islamic discourses. His selective engagement with Islamist movements, normalization of extremist narratives, omission of jihadist violence, and rhetorical demonization of secular institutions construct a body of work that enables the ideological infrastructure of radical Islamism.

He may not openly advocate violence, but his intellectual interventions provide legitimacy, grievance frameworks, and moral justification to groups and ideologies that pose existential threats to secular democracy in Bangladesh. In this way, Riaz functions not merely as an academic but as a sophisticated conduit for extremist soft-power—camouflaged in the language of scholarship.

The scholarly community, policymakers, and civil society must remain vigilant about such ideological subversions disguised as critical inquiry. The defense of truth, history, and secularism requires us to challenge not only armed radicals but also their intellectual enablers.

19. How We Explain Ali Riaz as an Opportunist Character

Ali Riaz’s academic and political trajectory presents a paradoxical case of ideological opportunism masked under scholarly activism. Despite his persistent criticisms of the secular values embedded in Bangladesh’s independence, Riaz has shifted his public positioning over the decades—conveniently aligning with different regimes, policy circles, and ideological lobbies to maximize his relevance within both Western academia and Bangladesh’s politically polarized media landscape. This section explores his opportunistic maneuvers through textual evidence, institutional affiliations, and his strategic silence on pressing humanitarian and political crises, revealing the calculated choices he makes to serve dual political and professional purposes.

19.1. Political Opportunism in Narrative Construction

Throughout his career, Ali Riaz has changed the tone and thematic direction of his writings based on prevailing global political moods and donor funding trends. His earlier works show little emphasis on condemning jihadist violence, while his later texts, such as God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh (2004), adopt a more moderate stance—although still providing apologetic frameworks for Islamist militancy. He maneuvers between narratives of victimhood (for Islamist groups) and moral relativism to retain credibility among both Western leftist think tanks and Islamist sympathizers in South Asia (Karim, 2016).

Riaz’s tendency to discredit secular nationalist leaders while simultaneously portraying radical clerics as legitimate stakeholders in democracy indicates a deeper opportunistic logic. By embracing Islamists as “legitimate political actors,” he inserts himself into Western academic conversations around political pluralism while undermining the Liberation War’s foundational narratives (Bashar, 2021).

19.2. Dual Allegiance: U.S. Citizenship and Subversive Engagement

Despite being a U.S. citizen and benefitting from Western democratic institutions, Riaz actively intervenes in Bangladeshi political debates with a tone that aligns with anti-secular and pro-Pakistani revisionism. His role in several Washington-based policy briefings and think tanks—including the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)—has enabled him to influence narratives that delegitimize Bangladesh’s democratic forces under the pretext of criticizing state overreach (Haider, 2022).

Riaz’s opportunism is also evident in his attempts to position himself as an “independent writer,” despite consistently working with lobbyists and publications linked to Jamaat-e-Islami and pro-Khaleda Zia networks. These affiliations rarely make it into his academic footnotes but are discernible through funding trails and citations in ideologically aligned publications (Chowdhury, 2023).

19.3. Strategic Silence on Islamist Atrocities

One of the most telling signs of Ali Riaz’s opportunism is his consistent silence—or downplaying—of Islamist atrocities. His works seldom confront the genocide of 1971 or the widespread rape and torture by Pakistani forces and their Islamist collaborators. This silence speaks volumes, especially given his detailed focus on state repression in the 21st century.

For instance, while Riaz wrote extensively about the Shahbagh Movement’s “majoritarian danger,” he failed to critically address the brutalities committed by those demanding the reinstatement of war criminals (Riaz, 2013). His avoidance of directly condemning Hefazat-e-Islam’s violent actions in Shapla Chattar (2013) or the burning of secular activists in 2014 reflects selective academic concern designed to maintain bridges with Islamist stakeholders.

19.4. Institutional Opportunism: Bending Academia to Ideology

Riaz has occupied strategic roles in Western academic institutions such as Illinois State University, where he produced work that increasingly blurred the line between academic neutrality and ideological positioning. His syllabi often exclude standard nationalist historiographies or critical literature on Jamaat-e-Islami’s war crimes. Meanwhile, his books are routinely promoted in South Asian Islamist student networks under banners of “Muslim empowerment” and “resistance to Western secularism” (Rahman & Dey, 2020).

He also contributes to journals and forums that have a record of Islamist sympathies, including Middle East Policy and Third World Quarterly, subtly shifting focus from state-sponsored Islamism to its so-called societal legitimacy. This re-framing allows him to appear as a balanced analyst while providing ideological cover to Islamist movements under the guise of political realism.

19.5. Media Opportunism and Political Lobbying

Riaz’s presence in media outlets such as Al Jazeera, TRT World, and pro-Jamaat Bangladeshi diaspora platforms reveals a calculated use of transnational media to project himself as a defender of democracy—ironically while allying with forces fundamentally opposed to democratic norms. During the 2018 and 2024 elections in Bangladesh, Riaz consistently amplified opposition narratives, even quoting unverifiable sources while ignoring electoral violence committed by Islamist factions.

His commentaries during the 2024 interim regime’s controversial rise were curiously muted on the role of radical groups who backed the so-called “civil society transition.” Instead, Riaz focused on the state’s surveillance mechanisms—an accurate but incomplete picture that omits the radical undercurrents threatening secular democracy (Kabir, 2025).

19.6. Opportunism in Constitution Discourse

Riaz has also been implicated in policy briefings aimed at reforming Bangladesh’s 1972 Constitution. His writings argue for the inclusion of Islamist groups in political processes under the pretense of “democratic inclusivity.” In reality, these arguments serve to dilute secularism and open space for extremist actors, reflecting opportunistic appeasement of radical ideologies rather than genuine political reform (Ahmed, 2023).

Conclusion: A Profile in Calculated Contradictions

Ali Riaz embodies the paradox of an academic who utilizes Western democratic tools to challenge secular nationalism and amplify Islamist narratives. His public persona as an “independent expert” masks deeper ideological entanglements and opportunistic recalibrations designed to secure relevance in both South Asian political discourse and Western academia.

The opportunism of Ali Riaz is not simply academic ambiguity—it is a pattern of selective advocacy, ideological alignment, and strategic silence that undermines Bangladesh’s historical truths, secular identity, and democratic future.

References

Ahmed, T. (2023). Constitutional Reforms and Religious Politics in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Liberty Press.

Bashar, Z. (2021). The Islamist Intellectuals of the Global South. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Chowdhury, M. (2023). Foreign Influence in Bangladesh’s Political Economy. Asian Affairs Journal, 54(2), 193–212.

Haider, A. (2022). Soft Islamism in Western Academia: The Case of Ali Riaz. Journal of South Asian Security Studies, 11(1), 44–63.

Kabir, R. (2025). Democracy in Crisis: Bangladesh’s 2024 Interim Regime. London: Pluto Press.

Karim, S. (2016). Islamism and the Politics of Legitimacy. Bangladesh Studies Review, 8(3), 66–89.

Rahman, F., & Dey, L. (2020). Curriculum, Politics and the Islamist Narrative. Global South Education Review, 7(1), 119–138.

Riaz, A. (2013). Shahbagh, the Middle Class and the Future of Politics in Bangladesh. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

Ayoob, M. (2008). The Many Faces of Political Islam: Religion and Politics in the Muslim World. University of Michigan Press.

Bergen, P. (2001). Holy War, Inc.: Inside the Secret World of Osama Bin Laden. Simon and Schuster.

Esposito, J. L. (1999). The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality? Oxford University Press.

Kepel, G. (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press.

Moghadam, A. (2006). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nasr, V. (2001). Islamic Leviathan: Islam and the Making of State Power. Oxford University Press.

Riaz, A. (2008). Islamist Militancy in Bangladesh: A Complex Web. Routledge.

Riaz, A. (2010). God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh. Rowman & Littlefield.

Roy, O. (2004). Globalized Islam: The Search for a New Ummah. Columbia University Press.

Stern, J. (2003). Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants Kill. HarperCollins.