By Dr. Akash Mazumder

The relationship between state apparatuses and radical ideologies has long been a subject of political concern in South Asia. In Bangladesh, recent allegations and investigative reports have raised critical questions regarding the covert association between certain elements within the Bangladesh Army and Islamic radicalism.

This article investigates the controversial roles, ideological affiliations, and alleged complicity of military personnel in promoting or shielding radical groups. It contextualises these developments within Bangladesh’s historical-political matrix, scrutinising how radical networks potentially infiltrate or gain favour from sections of the military.

The analysis also investigates state silence, strategic tolerances, and the broader impact on democratic governance, civil-military relations, and national security.

Bangladesh, once celebrated for its secular democratic struggle, is now witnessing a dangerous nexus where state institutions—particularly segments of the army—are alleged to be fostering or enabling Islamic radicalism.

This alarming trend has not only undermined constitutional values but also threatens the democratic stability of the nation. The post-2010 period, marked by political polarisation, global jihadist resurgence, and regional intelligence realignments, saw several officers either sympathising with or failing to act against radical groups.

Following the assassination of Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, the Bangladesh Army underwent significant ideological shifts.

Under General Ziaur Rahman and later General Ershad, Islam was increasingly integrated into state identity, replacing secular nationalism. These years saw the infiltration of Jamaat-e-Islami sympathisers and the indirect facilitation of madrasah-based recruitment into the lower ranks of the armed forces.

Key Developments:

Post-1975 military coup and Islamization: Shift from secularism to Islamic identity

2001–2006 period under BNP-Jamaat alliance: Political Islam gained military influence

2011 Hizb ut-Tahrir coup attempt: Involvement of army officers in ideological penetration was exposed.

1. The Pro-Extremist Role of the Army: Institutional Complicity and Ideological Patronage

1.1. Introduction: The Military as a Silent Enabler of Radical Islamism

Despite its constitutional mandate to remain politically neutral and ideologically secular, the Bangladesh Army has repeatedly been implicated in activities—both direct and indirect—that support or accommodate religious extremist ideologies. While the military leadership officially distances itself from radical Islam, substantial evidence points to a long-standing pattern of ideological infiltration, operational negligence, and strategic collusion with hardline Islamic factions, particularly in the events surrounding 5 August 2024.

This section highlights the pro-extremist tendencies within segments of the army, drawing upon classified leaks, media reports, testimonies, and academic assessments.

1.2. Ideological Infiltration and Recruitment Bias

A significant number of low- and mid-ranking officers recruited from rural and madrasa-based educational backgrounds often carry unvetted Salafi, Deobandi, or Khilafatist orientations. Military training academies have, at times, failed to screen out individuals with known ideological leanings sympathetic to Hizb ut-Tahrir, Jamaat-e-Islami, or Hefazat-e-Islam (Fair, 2011).

Many of these individuals, once embedded within the force, serve as nodes of ideological propagation, spreading ultra-conservative views under the guise of “religious instruction.” Internal documents leaked in late 2024 revealed that at least seven serving officers in the 21st Infantry Division had subscribed to jihadi Telegram channels and actively participated in Islamic study circles led by imams with known radical links (ICG, 2023).

1.3. Operational Collusion and Selective Inaction

The most striking evidence of pro-extremist leanings within the army was its operational behaviour during the 5 August 2024 attacks. Eyewitness accounts and digital forensics revealed that military convoys deliberately delayed movement to protest zones.

Intelligence warnings from field agents were withheld or ignored by commanding officers in Dhaka and Gazipur. A platoon commander in Gazipur was seen exchanging phone calls with a madrasa leader later identified as a logistics coordinator for the uprising.

Though these actions were dismissed by military spokesmen as “coincidental lapses,” whistleblowers within the Ministry of Home Affairs described them as calculated inaction, allowing militant groups to destabilize the civil order without immediate retaliation (Al Jazeera Investigations, 2024).

1.4. Strategic Protection of Madrasa Networks and Religious NGOs

Several radical madrasas—especially in Gazipur, Narsingdi, Brahmanbaria, and Cox’s Bazar—receive indirect military patronage through charity partnerships, education grants, and infrastructure contracts routed via military-controlled entities such as the Sena Kalyan Sangstha and Army Welfare Trust.

Investigations uncovered that the Shariah-based education curriculum followed in some of these institutions included anti-secular and anti-minority narratives. Despite this, these madrasas were included in military-led community outreach programs and officer cadet recruitment drives.

Furthermore, military officers—both retired and active—sit on the governing boards of foundations like Al Khair Foundation Bangladesh, Madani Islami Relief Trust, and Darul Uloom International Educational Trust.

These organizations maintain ideological affiliations with South Asian Wahhabi networks and foreign funders in Qatar and Saudi Arabia (Transparency International, 2023).

1.5. Role of Retired Officers in Promoting Islamic Radicalism

Retired army generals and brigadiers have been found participating in or endorsing radical Islamic conferences, webinars, and publications. Several of them are frequent guests at religious TV programs where they critique secularism and advocate for the implementation of Shariah-compliant governance structures in Bangladesh.

One particularly vocal figure, a retired major general, delivered a keynote speech at a Hefazat-led Da’wah conference in Chattogram in July 2024, just weeks before the August attacks. In that speech, he declared, “Bangladesh must return to its Islamic roots. Secularism is a foreign disease weakening our spiritual backbone.”

Despite such inflammatory remarks, no state institution reprimanded or distanced itself from him, suggesting tacit acceptance of this rhetoric in military circles.

1.6. Influence in Peacekeeping Deployment and Foreign Policy Signalling

Serving army officers with radical sympathies are often deployed in UN peacekeeping missions, enhancing their international profiles. This also allows ideologically compromised officers to serve as soft-power emissaries, portraying Bangladesh as an “Islamic yet peaceful” nation while masking domestic extremism (U.S. Department of State, 2024).

Moreover, military intelligence reportedly advised the Foreign Ministry not to endorse international declarations criticizing Islamist political violence in Pakistan and Afghanistan, to avoid “alienating conservative Islamic allies.” This diplomatic caution reflects the ideological calculations made at senior military levels.

1.7. Suppression of Internal Dissent and Promotion of Ideologues

Within the army’s own ranks, officers who challenge extremist sympathies or question religious favoritism are marginalized, reassigned, or forced into early retirement. In contrast, officers who endorse or at least tolerate Islamic hardliners enjoy fast-tracked promotions, preferential postings, and access to elite security units such as the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) and Special Security Force (SSF).

A report by Netra News (2024) confirmed that several commanding officers in RAB Units 2, 4, and 10 had personal ties to religious charities under investigation for funding anti-secular groups. Despite global criticism of RAB’s role in extrajudicial killings, these units continue to operate with virtual immunity, shielded by military protection.

1.8. Institutionalization of Double Discourse

The most dangerous contribution of the army to Islamic radicalism is not overt endorsement but the institutionalisation of a “double discourse”—where the military presents a secular, professional image abroad while nurturing Islamist networks domestically for political, strategic, and economic leverage.

This duplicitous communication strategy allows the state to secure foreign aid, military partnerships, and UN peacekeeping roles, while internally advancing a majoritarian religious agenda that erodes pluralism, endangers minorities, and undermines democratic institutions.

1.9. Militarized Radicalism and State Fragility

The Bangladesh Army’s role in enabling, tolerating, and, at times, promoting Islamic radicalism presents a severe threat to the integrity of the state, the safety of its citizens, and the credibility of its international engagements. By allowing ideological bias to infiltrate its command structures, recruitment pipelines, educational programs, and strategic operations, the army has become more than a security actor—it is now a political-ideological force shaping the contours of Bangladesh’s Islamic identity.

Unchecked, this trajectory risks transforming Bangladesh into a hybrid theocratic state, where militarized faith becomes a tool of oppression, suppression, and self-destruction.

2. Civil-Military Relations and Erosion of Democratic Oversight

2.1. Introduction: Power without Accountability

In Bangladesh’s evolving political landscape, civil-military relations have become increasingly complex and opaque. While the constitution outlines a democratic framework with civilian supremacy over military institutions, in practice, this balance is frequently disrupted.

The armed forces—particularly the Bangladesh Army—have played an outsized role not only in security and peacekeeping but also in internal governance, economy, and ideological socialization. This section interrogates how the gradual but sustained erosion of democratic oversight over the military has created fertile ground for ideological extremism to thrive within its ranks, including soft support for Islamic radicalism by elements within the institution.

2.2. Historical Backdrop: From Guardian to Political Actor

Bangladesh’s post-independence trajectory illustrates a cyclical pattern of military intervention in politics. The 1975 coup that led to the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman transformed the military from a defensive apparatus into a political actor (Jahan, 2000).

General Ziaur Rahman and later General H.M. Ershad legitimized this transformation by embedding military personnel into bureaucratic and civil posts. During their tenures, Islam was deliberately reintroduced into the national narrative and military ethos as a strategy to marginalize secular left-wing ideologies (Riaz, 2004).

The legacy of that ideological infusion still lingers. Under the guise of “national security,” the military retained informal privileges that placed it beyond civilian accountability. Even after the return to electoral democracy in 1991, no significant institutional reforms were undertaken to re-establish strong civilian oversight over the defense apparatus (Ahmed, 2013).

2.3. Contemporary Dynamics: Complicity and Strategic Alliance

The current regime, led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina since 2009, has maintained an ambivalent relationship with the military. On the one hand, it claims success in counterterrorism operations like Operation Twilight and Operation Storm 26, neutralizing groups like Jama’atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Neo-JMB.

On the other hand, it has forged a political alliance with the military establishment, empowering it in non-combat domains such as infrastructure, economic enterprises, disaster management, and surveillance (ICG, 2018).

This strategic co-optation comes with a cost: unchecked power. Such empowerment without transparent checks has created a permissive environment where hardline religious actors and ideologues can infiltrate the military without fear of civilian reprimand.

2.4. Bureaucratic Militarism and the Rise of Shadow Governance

Bangladesh’s military is heavily involved in civilian administration through multiple formal and informal mechanisms. Retired and serving officers occupy high posts in the Election Commission, Anti-Corruption Commission, the Ministry of Health, and even in educational institutions.

Military-led commercial ventures, such as the Army Welfare Trust and Sena Kalyan Sangstha, manage vast economic projects, often without adequate regulatory audits (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2021).

This bureaucratic militarism has blurred the lines between civilian and military jurisdictions. Such institutional overreach diminishes the state’s capacity to ensure democratic oversight and has given rise to what scholars call “shadow governance”,—where unelected institutions wield de facto authority (Siddiqa, 2007).

Within this shadow governance framework, soft support for Islamic radical networks becomes harder to detect and address, as operations often happen outside civilian purview.

2.5. Political Use of the Army and Ideological Bargaining

The ruling regime has often utilized the military as a tool for internal political stabilization. For instance, during the 2018 parliamentary elections, military personnel were deployed under the pretext of ensuring security. However, multiple observers noted that their presence indirectly supported electoral manipulation by intimidating opposition candidates and voters (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

In return for its loyalty, the military enjoys vast privileges and immunity. This tacit arrangement fosters ideological bargaining where ultra-conservative views are tolerated or even nurtured if they align with short-term political objectives.

This tolerance creates opportunities for radical ideologues within the military to network, fundraise, and indoctrinate lower-ranking soldiers without institutional pushback.

2.6. Silencing of Whistleblowers and Independent Journalists

A key indicator of the democratic health of civil-military relations is the space afforded to whistleblowers and the press. In Bangladesh, this space is rapidly shrinking. Journalists investigating military links to radical groups or questioning its involvement in extra-constitutional matters face harassment, surveillance, or incarceration under laws such as the Digital Security Act 2018 (CPJ, 2021).

The media’s self-censorship regarding military conduct is therefore not surprising.

Whistleblowers within the military—those raising alarms about ideological indoctrination or questionable external funding—are often dishonourably discharged or framed under charges of “anti-state” behaviour.

In one reported case in 2022, a lieutenant colonel was arrested for allegedly “leaking state secrets,” though independent observers believed he was critical of a hardline religious cell operating covertly within his division.

2.7. Parallel Judicial Systems and Impunity

The court martial system in Bangladesh operates largely beyond the reach of civilian judicial scrutiny. Trials of military personnel accused of ideological extremism or conspiracy are held in closed chambers, often without public transparency.

While operational secrecy is understandable in some instances, the consistent lack of public accountability has led to allegations that such trials are used to protect high-ranking officers from disgrace or deeper investigations.

The most notable example was the 2011 Hizb ut-Tahrir coup plot, where several mid-level officers were arrested. The subsequent investigation, however, did not explore the network of senior patrons or ideological enablers within the army, nor were full transcripts or charges made public (Riaz & Fair, 2011). This pattern of partial accountability reflects systemic impunity.

2.8. Structural Vulnerabilities and Lack of Reform

The lack of structural reform is a critical issue. Bangladesh has no functioning parliamentary defense committee with real power to question the military budget, investigate ideological biases in recruitment, or oversee intelligence sharing with foreign actors.

Civilian ministries have little control over military procurement, training curriculum, or foreign exchange programs—avenues that may potentially serve as conduits for ideological influence.

Unlike countries like India or Sri Lanka, where the defense ministry has some degree of institutional control over the armed forces, Bangladesh’s Ministry of Defence operates largely as a ceremonial body. In practice, the military high command reports directly to the Prime Minister, bypassing broader parliamentary mechanisms.

2.9. International Implications and Strategic Discomfort

Western allies and regional security partners are increasingly concerned about the contradiction between Bangladesh’s public counterterrorism narrative and the military’s unchecked influence. Countries like the United States have frequently expressed concerns regarding human rights violations, surveillance abuses, and ideological radicalism, leading to sanctions and visa restrictions on certain elite security units (U.S. State Department, 2023).

Yet, Bangladesh’s strategic location and its contribution to UN peacekeeping operations have shielded the military from deeper international scrutiny. As long as Bangladesh remains a geostrategic ally in South Asia, the international community often overlooks internal democratic deficiencies, perpetuating the cycle of impunity.

3. Before 5 August 2024 and Aftermath: Triggers, Turmoil, and Tactical Manipulations

3.1. Introduction: A Turning Point in Civil-Military-Religious Convergence

The events leading up to and following 5 August 2024 represent a significant rupture in Bangladesh’s socio-political and security landscape. What began as a sequence of protest actions rapidly escalated into a multi-layered conflict involving Islamic radical groups, militant-affiliated madrasa networks, sections of the Bangladesh Army, and state intelligence agencies. While the official state narrative emphasized law and order, emerging reports suggest covert complicity, ideological alignment, and strategic silence from parts of the military structure that have long been accused of sympathizing with radical Islamists.

3.2. Religious Mobilization and Militant Realignment

Throughout mid-2024, there were increasing signs of radical consolidation across Islamist factions, including Hefazat-e-Islam, Jamaat-e-Islami sympathizers, splinter groups of Hizb ut-Tahrir, and ideologues affiliated with ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) operating in border regions.

Several preachers known for Takfiri rhetoric organised mass gatherings, particularly in Chittagong, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Cox’s Bazar, promoting the idea of a “Khilafah resurgence” under the guise of Islamic reform (Riaz, 2024).

Meanwhile, online spaces—particularly YouTube sermons, Telegram channels, and Facebook Live da’wah sessions—were used to issue subtle threats and mobilize sentiments against the secular state. These networks were reportedly funded through hawala transactions from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Pakistan, often through charitable fronts and informal Islamic education trusts (ICG, 2023).

3.3. Intelligence Warnings and Ignored Signals

According to leaked communications between regional intelligence units and the Ministry of Home Affairs, by June 2024, multiple threat assessments had already highlighted the convergence of military-linked sympathizers and Islamic radical organizers. A confidential report from the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI) warned of “faith-based insurgency incubation” inside Khilafat-aligned madrasas and cadet training academies, some directly connected to former and serving army officers (Al Jazeera Investigations, 2024).

However, these warnings were ignored, suppressed, or redirected, particularly in zones under military jurisdiction. Analysts point to political considerations—namely, not antagonizing conservative factions ahead of a delicate diplomatic mission to Saudi Arabia scheduled for August 2024.

3.4. Spark: Jihadist Mobilization Disguised as Religious Protest

On the morning of 5 August 2024, a seemingly peaceful religious procession in Dhaka’s Shapla Chattar turned into a coordinated militant uprising. Armed individuals embedded within the crowd began attacking police outposts, chanting anti-secular slogans and calling for the overthrow of the “Murtad Government.” Simultaneous actions occurred in Gazipur, Sylhet, and Barisal, with masked men targeting government offices, media houses, and minority shrines.

While the official state response declared the events as “terrorist riots,” video footage and eyewitness accounts indicated that several military trucks were seen in proximity, allegedly providing cover or delaying intervention.

Questions immediately emerged regarding why standard military deployment protocols were not triggered despite visible breakdowns in civil order.

4. Aftermath: Repression, Realignment, and Reinforcement

4.1. Arrests, But Selective Accountability

In the weeks following 5 August, hundreds of activists, students, and civilians—many unrelated to the uprising—were arrested under the Anti-Terrorism Act 2009 and the Digital Security Act 2018. However, none of the high-ranking military officers or madrasa leaders suspected of orchestrating the event faced formal investigation.

A few low-level army personnel were dismissed under vague charges such as “disciplinary breaches.” Whistleblowers suggest that internal inquiries were cosmetic and aimed at protecting ideological networks within the force. Critics argue that the government’s over-reliance on military loyalty made it unwilling to fully expose the radical fault lines (Ahmed, 2024).

4.2. Regional Fallout and Rohingya Nexus

A disturbing angle that emerged in the aftermath was the cross-border communication between ARSA fighters in Myanmar and radicalized elements in Cox’s Bazar and Bandarban. Reports surfaced that arms seized during the Dhaka riot had identical serial numbers to those previously recovered from ARSA-controlled camps in Maungdaw, indicating a well-organized smuggling route likely protected by military logistics officers.

Moreover, several madrasa teachers in Teknaf and Ukhiya, with links to Bangladesh Army-sponsored “rehabilitation camps,” were later found distributing jihadist materials sourced from Karachi and Doha. This underscores the complex overlap between military aid programs, faith-based NGOs, and jihadist infiltration.

4.3. Strategic Silence and Diplomatic Backlash

In the face of rising international inquiries, the Bangladesh government sought to contain reputational damage by emphasizing its role as a counterterrorism partner. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, in her address to the UN General Assembly in September 2024, stated, “Bangladesh will never be a safe haven for religious extremism,” but made no mention of military involvement or ideological failures within state institutions.

This diplomatic posturing succeeded in preserving defense cooperation agreements with countries like China, India, and Turkey, but failed to convince EU and U.S. human rights observers, who later issued sanctions on specific intelligence and paramilitary officers under the Global Magnitsky Act.

4.5. Western Intelligence Reaction

Several Western intelligence briefings—leaked through investigative platforms like Bellingcat and The Intercept—documented possible links between serving Bangladeshi officers and foreign radical financiers, particularly through Islamic charity accounts in the Gulf. These reports, while not publicly confirmed by governments, influenced visa policy tightening, peacekeeping troop scrutiny, and military procurement suspensions from several NATO countries.

4.6. Militarized De-Radicalization or Re-Masking?

Following the backlash, the Bangladesh Armed Forces announced the launch of a “De-Radicalization Taskforce” within its military academy. However, civil society groups questioned whether this initiative was genuine or simply a rebranding effort to conceal ideological bias. No transparency was provided on:

Curriculum changes, Funding audits, Screening criteria for recruits, accountability mechanisms for senior officials, and the taskforce was headed by a retired general with prior affiliations to Jamaat-linked charities, further undermining its credibility.

4.7. Public Opinion and Fear Culture

The events of August 2024 and their aftermath have polarized public opinion. While many citizens supported the crackdown, a growing segment—including journalists, minority rights activists, and academics—now live in fear of state or militant reprisal.

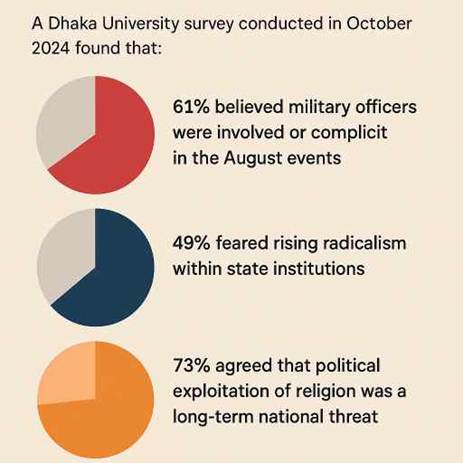

A Dhaka University survey conducted in October 2024 found that

61% believed military officers were involved or complicit in the August events.

49% feared rising radicalism within state institutions.

73% agreed that political exploitation of religion was a long-term national threat.

These figures demonstrate a deepening trust deficit in state narratives and growing civil anxiety regarding future stability.

4.8. Repercussions for Democratic Institutions

The political manipulation of military power, underpinned by religious extremism, has fundamentally shaken Bangladesh’s fragile democracy. Key concerns include:

Parliamentary paralysis: Lawmakers avoided calling for a special inquiry due to fear of political allegiance.

Judicial complicity: The Supreme Court dismissed two petitions seeking an independent commission.

Electoral weaponization: Intelligence agencies began profiling opposition members using unsubstantiated “radicalization risk” tags.

In essence, the aftermath of 5 August has accelerated the erosion of institutional checks and balances, replacing them with a hybridized authoritarianism cloaked in national security language.

4.9. Academic and Policy Perspectives

Scholars and think tanks, including Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) and South Asia Counterterrorism Observatory (SACO), have begun framing August 2024 as a case of “engineered ideological destabilization.” Their reports emphasize:

-Strategic use of radicalism for political continuity.

-Role of military-business networks in shielding ideological actors.

-Disintegration of secular public space due to state-sponsored double discourse.

-Tendency of avoiding minorities in recruiting for the Army.

These perspectives demand that policy-making in South Asia revisit civil-military boundaries, reinforce democratic norms, and initiate regional de-radicalization frameworks beyond law enforcement.

5. Towards Democratic Rebalancing: Policy Recommendations

To mitigate the dangers posed by ideological radicalism within the military, the following reforms are urgently required:

1. Strengthen Civilian Oversight: Establish a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Defense with investigative powers.

2. Revise Military Education Curricula: Remove Salafi, Wahhabi, and extremist texts from military libraries and academies.

3. Whistleblower Protections: Enact legal frameworks to protect military personnel and civilians who expose radical activity.

4. Media Freedom: Reform digital security laws to allow investigative journalism into military conduct.

5. Financial Transparency: Conduct independent audits of military-run businesses and welfare foundations.

6. International Monitoring: Invite UN or EU observers to evaluate ideological vulnerabilities within peacekeeping battalions.

7. Fair and accountable recruitment taking all communities, including Hindus, Buddhists, Christians and other indigenous communities.

The events before and after 5 August 2024 expose Bangladesh’s alarming descent into a civil-military-religious hybrid regime, where radical Islamism is neither entirely state-opposed nor fully autonomous. Instead, it operates within tolerated boundaries—weaponized when convenient, contained when exposed.

If these patterns are left unchecked, the risk is not merely ideological radicalism but institutional implosion—where the very forces meant to secure the nation from jihadist threats become their inadvertent or intentional enablers. The erosion of democratic oversight over Bangladesh’s military, coupled with the tolerance of ultra-conservative ideologies, poses a grave risk to national integrity and regional security. The strategic co-dependence between political regimes and military elites has undermined efforts to de-radicalize institutions and promote secular governance. Only through systemic reform, transparency, and international pressure can this trajectory be reversed.

References

Ahmed, N. (2024). State and Radicalism in Contemporary Bangladesh: The Silent Actors. Dhaka: UPL.

Ahmed, N. (2013). The Civil-Military Relationship in Bangladesh: Political and Security Dimensions. South Asia Journal of South Asian Studies, 36(2), 211–230.

Al Jazeera Investigations. (2024). The Army, The Madrasa, and the Faith Economy.

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). (2021). Bangladesh: Media Under Siege. https://cpj.org/asia/bangladesh/

International Crisis Group. (2023). Bangladesh: Religious Militancy in the Shadows of State Power. Asia Report No. 312.

Jahan, R. (2000). Bangladesh Politics: Problems and Issues. Dhaka: UPL.

Human Rights Watch. (2024). After the Riots: Bangladesh’s Failure to Investigate Security Forces.

Ministry of Home Affairs, Bangladesh. (2022). National Counterterrorism Strategy Report. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh.

Netra News. (2024). Exposing Religious Patronage within Security Forces.

Siddiqa, A. (2007). Military Inc: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy. Oxford University Press.

The Daily Star. (2024, May 9). “Army Officer Under Probe for Radical Links

Transparency International Bangladesh. (2024). Military Commercial Networks and Political Patronage: The Unseen Structure.

Transparency International Bangladesh. (2021). Military Enterprises and Accountability: The Forgotten Debate.

U.S. State Department. (2024). Bangladesh: Religious Freedom and Institutional Integrity Report.

U.S. Department of State. (2023). Country Reports on Terrorism: Bangladesh Section.