By Dr. Akash Mazumder, P. K Sarker

Mapping the Funding Networks

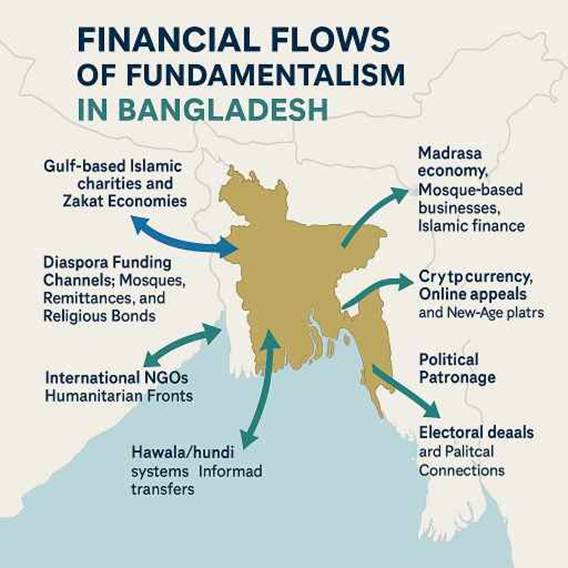

The funding infrastructure sustaining religious fundamentalism in Bangladesh is diverse, dynamic, and increasingly sophisticated. This chapter maps the economic pipelines that have historically financed—and continue to enable—the ideological and logistical functioning of Islamist networks. These sources range from traditional religious charities based in the Gulf to emergent digital financial tools like cryptocurrencies. While this chapter avoids generalizing all Islamic financial activities as inherently linked to militancy or fundamentalism, it critically explores how certain sectors within these systems are co-opted, manipulated, or strategically employed to serve radical agendas.

1. Gulf-based Islamic Charities and Zakat Economies

Gulf-based Islamic charities have played a significant role in shaping the ideological and institutional landscape of Bangladeshi Islamism since the late 1970s. Following the rise of petrodollar economies and Saudi Arabia’s increased investment in pan-Islamic solidarity, many Gulf charities began channeling zakat (obligatory Islamic alms) and sadaqah (voluntary donations) to underdeveloped Muslim-majority nations, including Bangladesh. Institutions such as the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), the Muslim World League, and the Kuwait-based Revival of Islamic Heritage Society became major players in this financial ecosystem (Levinson, 2020).

These organizations often funded the construction of mosques, madrasas, orphanages, and hospitals. While many of these initiatives contributed positively to poverty alleviation and social development, some charities—either intentionally or through lack of oversight—also supported entities that promoted ideological extremism or served as logistical covers for radical activities (Burr & Collins, 2006).

Understanding the Yunus–Pakistan nexus

‘I am a militant’ slogan chanted, al-Qaeda flags displayed again in Dhaka

The zakat economy, in this context, operates as both a spiritual obligation and a political economy. As a redistributive mechanism, zakat channels vast sums annually across borders with minimal state oversight. Saudi Arabia’s annual zakat budget, for instance, has been estimated to run into billions of dollars, some of which is disbursed to non-governmental partners in South Asia. In Bangladesh, this translates into parallel welfare networks often beholden more to transnational Salafi or Deobandi agendas than to national policy frameworks (Kabir, 2013).

2. Diaspora Funding Channels: Mosques, Remittances, and Religious Bonds

The Bangladeshi diaspora—particularly in the United Kingdom, the Middle East, and the United States—has emerged as a crucial source of funding for religious institutions and ideological movements. Diaspora-led fundraising campaigns, mosque-endorsed charity drives, and transnational religious networks allow funds to flow toward causes that resonate with ideological convictions abroad.

One critical vector of this financial flow is the mosque. In cities like London, Birmingham, and New York, Bangladeshi-run mosques regularly host fundraising events for orphanages, Islamic schools, and “humanitarian causes” in Bangladesh. While most of these donations are legitimate and well-intentioned, investigative reports have revealed instances where these funds are misappropriated or diverted to fronts linked with political Islam or Jamaat-e-Islami-affiliated institutions (Khan, 2015).

Remittances—Bangladesh’s second-largest source of foreign exchange—also form an informal but powerful means of support. According to World Bank (2021) estimates, Bangladesh received over $21 billion in remittances in 2020. A portion of this sum is channeled not only to families but also to community trusts, village mosques, and regional da’wah movements. These transactions are rarely scrutinized for ideological affiliations or the potential use of funds in promoting radical ideologies (Rahman, 2019).

Jihadi infiltration in Bangladesh Army: Recent controversial activities

Holey Artisan Carnage: Why is Yunus patronising Islamic State jihadists?

Additionally, religious bonds such as wakf (endowments) and qard hasan (interest-free loans) are often embedded within diaspora networks. These forms of funding, deeply rooted in Islamic financial jurisprudence, provide capital for religious institutions, some of which subtly propagate anti-secular narratives or sectarian agendas (Karim, 2014).

3. Hawala/Hundi Systems and Informal Transfer Mechanisms

Informal money transfer systems like hawala and hundi have long been a preferred mechanism for moving funds across borders in South Asia, bypassing formal banking regulations and state oversight. These networks operate through trust-based relationships and offer low-cost, rapid transfers, making them attractive to both legitimate users and illicit actors.

Hawala has been exploited by various Islamist networks to fund militant and ideological operations without detection (Passas, 2006). In the Bangladeshi context, hundi networks are often interlinked with labor migration routes. Workers send money through informal couriers or brokers who disperse the funds to local religious or political actors. These networks lack transparency and regulatory frameworks, creating ample room for abuse.

Law enforcement agencies have intermittently cracked down on hundi operations, particularly when linked to high-profile terror incidents. For example, investigations into the 2016 Holey Artisan attack in Dhaka revealed that some of the attackers received logistical support financed via informal transfers (Hasan, 2017).

4. International NGOs and Humanitarian Fronts

Some international NGOs and humanitarian organizations, operating under the guise of development and relief work, have been implicated in inadvertently supporting radicalization. This does not imply that all NGOs are complicit, but rather that the lack of stringent due diligence, especially during crisis response efforts (e.g., refugee camps), can allow funds and resources to be co-opted.

The Rohingya refugee crisis provides a salient example. With over one million refugees in Cox’s Bazar, a plethora of foreign NGOs rushed to provide humanitarian assistance. However, a subset of these NGOs reportedly engaged local partners without proper vetting, some of whom were linked to political Islamic groups or used the opportunity to recruit or proselytize (ICG, 2019).

Moreover, the opaque nature of financial transactions among NGOs—especially those not registered with the Bangladesh NGO Affairs Bureau—creates gaps in accountability. Radical networks have capitalized on this by forming their own NGOs or partnering with sympathetic organizations to receive foreign aid under a humanitarian pretext (Hossain, 2021).

5. Cryptocurrency, Online Appeals, and New-Age Platforms

The digital age has ushered in a new paradigm of financial mobilization. Cryptocurrencies, crowdfunding websites, and encrypted communication platforms now allow radical actors to bypass traditional gatekeepers and regulatory institutions.

Cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin and Ethereum have increasingly been adopted by jihadist networks worldwide for anonymous transactions (Weimann, 2021). While still nascent in the Bangladeshi context, there are growing concerns about the use of cryptocurrencies to finance radicalization efforts. For instance, online jihadist forums occasionally issue calls for donations in crypto wallets, which are difficult to trace and regulate.

Furthermore, online appeals through platforms like Telegram, WhatsApp, and Facebook offer low-cost, high-impact fundraising mechanisms. Video content featuring suffering Muslims, Quranic appeals, and calls for ummah solidarity are circulated widely to solicit donations from emotionally primed audiences (Ali, 2022). These campaigns often present themselves as humanitarian initiatives, but the absence of regulatory oversight makes it nearly impossible to determine the end use of the funds.

In addition, platforms like Patreon and GoFundMe have, in some documented instances, hosted fundraising campaigns for Islamic charities without adequate scrutiny. Although these platforms enforce community guidelines, loopholes and user anonymity often make enforcement inconsistent and reactive.

The economy of fundamentalism in Bangladesh is deeply enmeshed within a global matrix of religious diplomacy, ideological propagation, financial patronage, and strategic geopolitical interests. Various foreign state and non-state actors, including Gulf monarchies, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and Western governments, interact with Bangladeshi Islamist movements through funding, soft power outreach, and religious networks. These global linkages shape the ideological contours, financial sustainability, and political leverage of fundamentalist actors in Bangladesh. This chapter critically examines the multidimensional foreign influences shaping Bangladesh’s Islamist economy and their implications for national security and sovereignty.

6. Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi Outreach

Saudi Arabia remains a principal exporter of Wahhabi Islam and religious diplomacy to South Asia, including Bangladesh. The Kingdom’s religious missions, funded through institutions such as the Muslim World League (MWL) and the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), channel financial support and ideological training to Bangladeshi madrasas, mosques, and Islamic charities (Keating, 2014).

Saudi-funded scholarships and religious curricula have helped entrench Salafi-Wahhabi interpretations within Bangladesh’s Islamist milieu, often marginalizing indigenous Islamic traditions such as Sufism and the Hanafi school (Riaz, 2004). Moreover, Saudi religious diplomacy emphasizes loyalty to the monarchy and orthodox interpretations, which influence political alignments within Bangladesh’s Islamist groups.

7. Qatar’s Strategic Religious Patronage

Qatar’s growing influence in Bangladesh is linked to its broader foreign policy of religious soft power combined with economic diplomacy. Through Qatar Charity and related foundations, the country funds educational institutions, relief projects, and religious centers (Henderson, 2020).

Qatari religious diplomacy tends to focus on humanitarian narratives, often blending aid with ideological propagation. Its support for youth engagement programs and mosque networks in Bangladesh fosters grassroots Islamist mobilization, which can be politically sensitive given the country’s volatile sectarian landscape.

8. United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Religious Funding

The UAE’s role is more nuanced, combining economic investments with support for Islamic institutions that align with its moderate Sunni vision. UAE-based charities and foundations provide grants to madrasa education, mosque construction, and zakat funds in Bangladesh (Schwarz, 2020).

However, concerns have been raised about indirect funding channels through which extremist-linked groups might receive material support, often facilitated by complex corporate and charity networks based in Dubai’s free zones (ICG, 2014).

9. Role of Turkish, Iranian, and Pakistani Outreach Programs

Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) has expanded its global footprint, including in Bangladesh, through mosque diplomacy, clerical training, and scholarship programs (Çakmak, 2019). Turkish NGOs, such as the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), engage in humanitarian aid with religious undertones.

Diyanet promotes a Sunni Hanafi orthodoxy and frames Islam within a narrative of modernity and governance consistent with Turkish state interests. Its outreach provides an alternative to Gulf Wahhabism and fosters political goodwill between Bangladesh and Turkey.

10. Iran’s Shia Networks and Cultural Diplomacy

Iran’s engagement in Bangladesh is comparatively limited but growing, focused on cultural diplomacy and supporting Shia communities and educational programs (Keddie, 2012). Iran funds religious centers and seminaries promoting Twelver Shiism, representing a minority sect in Bangladesh.

Iranian outreach also carries geopolitical significance given regional Sunni-Shia tensions and Bangladesh’s Sunni-majority population. Tehran’s soft power aims to build cross-sectarian bridges but sometimes exacerbates sectarian anxieties.

11. Pakistan’s Historical and Ideological Ties

Pakistan’s influence on Bangladesh’s Islamist movements stems from the shared legacy of the 1947 Partition and the 1971 Liberation War’s aftermath. Islamist groups in Bangladesh have ideological sympathies and informal networks linking them to Pakistani jihadi and Deobandi organizations (Rashid, 2023).

Pakistan-based seminaries and militant groups have provided ideological training and logistical support to some Bangladeshi Islamist factions, especially in border areas. These ties complicate Bangladesh’s counterterrorism efforts and regional security dynamics.

12. Cross-Border Funding with Indian, Rohingya, and Myanmar Ties

Bangladesh’s porous border with India facilitates cross-border religious and financial linkages. Islamist groups in West Bengal and Assam maintain contacts with Bangladeshi counterparts, enabling the flow of funds, literature, and cadres (Ahmed, 2021).

Indian Islamist charities and mosques linked to Jamaat-e-Islami and other groups often raise funds that are clandestinely transferred to Bangladesh’s fundamentalist networks, leveraging familial and ethnic ties across borders.

13. Rohingya Crisis and Militant Financing

The ongoing Rohingya refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar has become a hotspot for militant fundraising and recruitment. Islamist groups exploit humanitarian appeals to channel donations from transnational Islamist charities to refugee camps, where extremist ideologies have found footholds (ICG, 2020).

These funds sometimes finance militant training camps and support networks linked to both local and regional jihadist groups, complicating Bangladesh’s security and humanitarian response.

14. Myanmar’s Border Dynamics

Myanmar’s Rakhine state, with its complex ethno-religious conflicts, interfaces with Bangladesh’s security concerns. Cross-border smuggling and illicit finance networks connected to Buddhist nationalist militias and Islamist insurgents undermine stability.

Bangladeshi Islamist groups receive material and ideological support from sympathizers in Myanmar, further regionalizing fundamentalist finance and militancy (Riaz, 2018).

15. Western Governments’ Role: Policy Blind Spots and Diplomatic Constraints

Western governments, particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, have provided counterterrorism assistance and development aid to Bangladesh aimed at strengthening governance and financial regulation (US State Department, 2022).

However, policy blind spots persist, notably in addressing the religious and ideological dimensions of fundamentalism and in regulating charitable giving linked to diaspora communities. These gaps create vulnerabilities that militant financiers exploit.

16. Diplomatic Constraints and Realpolitik

Diplomatic relations with Gulf monarchies and strategic partners limit Western pressure on religious funding originating from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE. Geopolitical priorities—such as energy security and regional alliances—often supersede human rights or counter-radicalization concerns (Henderson, 2020).

This realpolitik dynamic constrains comprehensive global coordination on cutting off financial flows to Islamist fundamentalism in Bangladesh.

17. Gloal Salafi Networks and Bangladesh as a Strategic Hub

Bangladesh occupies a strategic position within the global Salafi movement, serving as both a recipient and node in transnational ideological and financial networks. Salafi clerics and institutions in Bangladesh are connected to Gulf-funded global Salafi centers, facilitating doctrinal exchange and funding (Rashid, 2023).

Bangladeshi Salafi scholars participate in international conferences, media, and online platforms, amplifying influence and mobilizing resources.

18. Media and Digital Da’wah Platforms

Bangladeshi Islamist groups increasingly leverage digital media to connect with global Salafi audiences, solicit funds, and disseminate ideology. Social media channels, encrypted messaging apps, and cryptocurrency-based donations bypass traditional oversight (US Treasury, 2022).

This digital dimension enhances Bangladesh’s role as a strategic hub for the transnational propagation of Salafi fundamentalism.

Conclusion

The global dimensions of Bangladesh’s economy of fundamentalism reveal a complex interplay of religious diplomacy, ideological exportation, and strategic geopolitical interests. Gulf states, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and regional actors all influence Bangladesh’s Islamist landscape through funding, education, and soft power. Meanwhile, Western governments’ policy limitations and diplomatic constraints hinder cohesive global action. Recognizing Bangladesh’s role as a critical node in global Salafi networks is essential for developing effective countermeasures that balance security with respect for sovereignty and development needs.

References

Ahmed, N. (2021). Diaspora, Faith and Politics: British-Bangladeshis and Transnational Islam. London: Routledge.

Çakmak, M. (2019). Turkey’s Religious Diplomacy and Diyanet’s Global Expansion. Turkish Studies, 20(4), 579–598.

Henderson, S. (2020). Qatar and Religious Soft Power: Charity and Diplomacy. Middle East Policy, 27(3), 84–101.

ICG. (2014). The Dark Side of Transition: Violence Against Muslims in Sri Lanka. International Crisis Group.

ICG. (2020). The Rohingya Crisis and Regional Security. International Crisis Group.

Keating, M. (2014). Islam and Charity: Understanding the Global Reach. London: Hurst.

Keddie, N. R. (2012). Iran’s Cultural Diplomacy in South Asia. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 44(3), 399–414.

Rahman, T. (2020). The Regulatory Ambiguities of Religious Charities in Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Legal Studies, 8(3), 214–230.

Rashid, S. (2023). Financial Jihad: Islamic Networks in the Age of Cryptocurrency. Dhaka: Prothoma.

Riaz, A. (2004). God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh. Rowman & Littlefield.

Riaz, A. (2018). Voting in a Hybrid Regime: Explaining the 2018 Bangladeshi Election. Journal of South Asian Studies, 41(3), 387–406.

Schwarz, R. (2020). Dubai: Global City and Islamic Finance Capital. Globalizations, 17(5), 879–895.

US State Department. (2022). Country Reports on Terrorism: Bangladesh. Washington, D.C.

US Treasury. (2022). Treasury Sanctions Individuals and Entities Linked to Terrorist Financing Networks. Washington, D.C.