The demolition of the Seven Liberation War murals along Bijoy Sarani, a historic thoroughfare in Dhaka named “Mrityunjayee Prangan”, has ignited a fierce controversy, with critics accusing the interim government led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus of orchestrating a deliberate erasure of Bangladesh’s independence heritage.

These murals, vibrant testaments to the Language Movement of 1952, the 1971 Liberation War, and the nation’s hard-fought victory, are now being dismantled under government orders, sparking outrage among citizens who view them as sacred symbols of national identity.

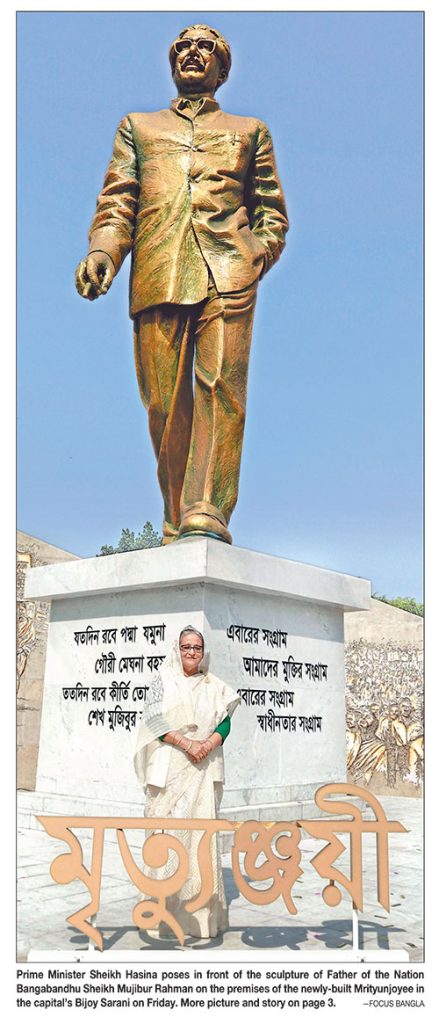

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina inaugurated the “Mrityunjayee Prangan” on Dhaka’s Bijoy Sarani on November 10, 2023, adorned with several murals depicting the pivotal role of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Bangladesh’s freedom struggle.

During the ceremony, the premier also unveiled a large sculpture of the Father of the Nation at the heart of the premises. The murals adorning seven walls along the premises were previously showcased at the Victory Day parades in 2021 and 2022 to widespread acclaim.

The seven walls covered in murals depicted the events of the 1952 Language Movement, the nationalism and cultural upsurge from 1954-60, the Six-Point Movement and mass uprising, the 1970 elections, the 1971 Liberation War, Bangabandhu’s March 7 speech, and the victory of December 16, 1971.

On August 5, radical Islamists destroyed all sculptures of the Liberation War and Bangabandhu in a planned way. They also damaged museums and cultural heritage.

The current demolition project, initiated on June 15, 2025, involves heavy machinery and a team of 50 workers, overseen by the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) under a Tk5 crore budget.

The government claims the site is being cleared for a “modern urban development project,” including a 10-lane highway and commercial complex, with construction slated to begin in August 2025. However, no detailed environmental or heritage impact assessment has been released, fueling suspicions of ulterior motives.

However, sources say the Jamaat-controlled interim government wants to build a Gono Minar in memory of the anti-government protesters who died in July-August.

On June 20, the “Gono Minar Implementation Committee” held a press conference at the Madhur Canteen of Dhaka University and announced that a program has been taken to collect public donations to ensure the involvement of the masses in this initiative.

Mobocracy: July Revolution appearing as Sniper Revolution

ICT-BD: Tribunal replaces pro-Jamaat lawyer in Sheikh Hasina’s contempt case

July Conspiracy: Gazetted lists contain many fake martyrs, injured fighters

Special benefits, law for July martyrs, warriors amid row over fake lists

The committee wants to give a preliminary visual appearance to this monument by August 5. Their plan has been arranged throughout the entire Bijoy Sarani.

Dhaka North City Corporation sources said they will build a sculpture and open space in memory of the July martyrs there. This decision was approved at the seventh corporation meeting (board meeting) of Dhaka North City on June 25.

The issue of constructing this sculpture was on the agenda as number 6 of the meeting. Apart from this, the DNCC has undertaken seven more projects or schemes in memory of the July martyrs. These include the construction of various stages, mass monuments, wall paintings, photo exhibitions, and arches.

A DNCC official told Prothom Alo on condition of anonymity that the proposed design of the sculpture is in the approval process. The proposal has a design of a sculpture of two people standing with a victory flag. Once the design is finalised, a tender will be invited for the work.

Allegations of a pro-Pakistani agenda, anti-liberation plots, and the murder of democracy have surged, with the Yunus administration facing accusations of aligning with razakar successors, Jamaat-e-Islami, and extremist groups like the National Citizens Party (NCP) to reverse Bangladesh’s secular, liberation ethos.

Critics, including Awami League leaders, argue this is a calculated move to obliterate Bangladesh’s liberation narrative.

Awami League General Secretary Obaidul Quader condemned the act, stating: “This is a sinister plot by Yunus and his NCP allies to erase the sacrifices of millions who fought Pakistan’s tyranny. The murals are not just art; they are our soul.”

He pointed to the government’s failure to prosecute war criminals fully, contrasting it with the Awami League’s post-1971 trials under the International Crimes Tribunal.

Historians like Professor Muntassir Mamoon echo this, asserting: “Destroying these murals is an attack on our collective memory, a step toward reimposing a pro-Pakistan, religion-based identity that the Liberation War rejected.”

Government officials defend the decision, framing it as progress.

DNCC Administrator and radical Islamist Mohammad Ejaz insisted: “The murals are deteriorating, and this project will boost traffic flow and economic growth. We’re preserving history in museums, not on roadsides.”

Chief Adviser Yunus, in a press conference on June 20, dismissed the criticism as “political propaganda,” saying: “Our focus is on development, not rewriting history. The NCP is a democratic party, not an extremist mob.”

However, his refusal to address the lack of public consultation or the murals’ cultural value has deepened distrust.

Social media posts reflect public anger, with users labeling the demolition a “cultural genocide” and accusing Yunus of pandering to BNP-Jamaat factions, historically linked to pro-Pakistan sentiments during 1971.

The controversy ties into broader allegations of a pro-Pakistani agenda. Critics claim Yunus, alongside the NCP—formed by former ADSM leaders—empowers Razakar descendants and Islamist groups to infiltrate state institutions.

The NCP, criticised for its opaque leadership and alleged ties to Jamaat-e-Islami, is accused of orchestrating the mural’s removal to align with an anti-liberation narrative. This follows reports of other symbolic erasures, such as the removal of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s portrait from school oaths and the vandalism of the Mujibnagar Surrender Statue in August 2024.

BNP leader Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir countered: “Yunus is not anti-liberation; he’s pragmatic. But his silence on NCP excesses is troubling.” Yet, the BNP’s own alliance with Jamaat, which opposed the 1971 war, undermines its moral stance, complicating the political discourse.

Social media reactions amplify the divide. On Facebook, activists like Umama Fatema, a former ADSM spokesperson, have condemned the demolition, aligning with her recent critique of student movement corruption.

Netizens call it a “Yunus-Yahya Khan redux,” referencing the 1971 Pakistani dictator, with hashtags like #SaveLiberationHeritage trending.

Conversely, NCP supporters argue that old murals can’t feed the poor; development is liberation too, reflecting a pragmatic, if controversial, defense. The polarised sentiment underscores a nation grappling with its past and future.

The government’s justification—that the murals obstruct urban planning—lacks credibility without transparency.

The rushed timeline, with demolition 80% complete by June 28, suggests political urgency over public interest.

The Yunus administration’s response has been defensive.

Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam stated: “Allegations of a pro-Pakistani agenda are baseless; we’re building a modern Bangladesh.”

Yet, the lack of a preservation plan for the murals—unlike the proposed July Revolution Memorial Museum—contradicts this.

Critics like Professor Amena Mohsin argue: “This is a pro-Pakistan tilt, reviving the Razakar ideology that 1971 defeated.”

Historically, Bangladesh’s identity hinges on 1971, with the Liberation War costing 3 million lives. The murals, visited by 500,000 annually, were educational tools, especially for young people.

Their destruction risks severing this link, a concern raised by student groups like Chhatra Federation, which demand a halt. Government officials counter that digital archives will preserve history, but this fails to address the loss of public symbolism.

As demolition nears completion, the debate intensifies.

The Yunus government’s development push has clashed with its democratic legitimacy, eroded by the Awami League ban and 140,000 arrests.

Critics see a pattern: erasing liberation symbols to appease Islamist factions, potentially turning Bangladesh into a “new East Pakistan.” Without reversal, this could deepen societal rifts, with social media amplifying calls for resistance. The murals’ fate may define Yunus’ legacy—progress or betrayal.