By Dr. Akash Mazumder

1. Introduction

On July 16, 2025, the district town of Gopalganj, Bangladesh, became the site of a tragic and unprecedented episode of political violence. A procession led by the National Citizen Party (NCP), (unregistered political party) as part of their “March to Gopalganj,” was met with local people resistance from alleged members of the Bangladesh Awami League (AL) and its youth wing Chhatra League, with apparent collusion from state forces in favour of NCP. Multiple individuals were killed, dozens injured, and several detained, triggering curfews and widespread condemnation.

This incident has prompted intense scrutiny from civil society, legal observers, and international human rights organizations. The use of force, suppression of peaceful assembly, and potential extrajudicial killings raise serious concerns under international human rights law, international humanitarian law, and principles of transitional justice.

Bangladesh has historically maintained a complex relationship with international law. Although it is a signatory to several UN human rights instruments, enforcement has often been selective or politically driven. Recent developments—including amendments to the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973—have expanded jurisdiction beyond war crimes of 1971 to include crimes committed in political conflicts in contemporary times, creating legal avenues for prosecution of July 2024 and 2025 mass violence.

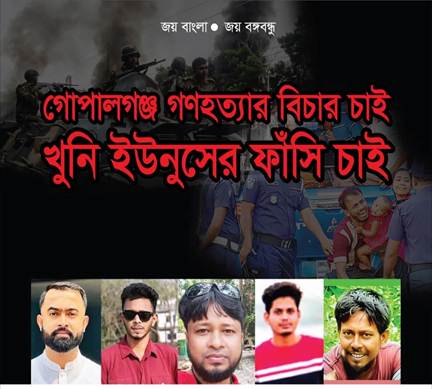

Bangladesh Army’s Brutality in Gopalganj: A state-sponsored massacre demanding global accountability

Complaint filed at ICC against 3 army officers, Yunus-Waker for Gopalganj massacre

This article critically examines the Gopalganj Massacre in light of applicable international conventions, treaties, and customary legal standards. It assesses the violations of the right to life, freedom of assembly, political expression, and identifies legal precedents that guide both domestic and international accountability mechanisms.

2. What happened?

In the wake of the 2024 unconstitutional transition in Bangladesh, political volatility intensified. The Awami League, which had successfully governed Bangladesh for over a decade until being disbanded under charges of orchestrating political violence, allegedly continued underground operations. On 16 July 2025, the NCP (unregistered political party) organized a mass rally with weapons in Gopalganj—considered a political stronghold of the ruling Awami family.

Eyewitness accounts, independent news agencies, and video footage from social media confirm that the rally began peacefully in the morning hours. As it progressed through Gopalganj town, NCP members were reportedly ambushed by masked individuals wielding sticks, petrol bombs, and bricks. The attackers were allegedly supporters of the AL, with police and paramilitary troops (RAB) providing indirect or passive support to safe mass people.

Security forces were then seen firing tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition, used Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) in safe transit of NPC members resulting in five confirmed deaths:

-Dipto Saha (BSL student activist)

-Ramzan Kazi

-Sohel Molla

-Emon Talukder

Another, who died later in Dhaka Medical College Hospital, was identified as Ramzan Munshi.

The confrontation lasted several hours. Numerous protesters were hospitalized with bullet wounds, some with critical injuries. Curfews were imposed by evening, and more than 3,000 individuals were later sued, with over 250 arrests made by July 20, 2025 (New Age, 2025).

Post-incident concerns

No autopsies were initially conducted; families allege the bodies were taken without consent.

Human rights groups, including Human Rights Forum Bangladesh (HRFB), have demanded a judicial probe and formal murder charges.

3. International legal frameworks: A lens of justice

3.1 International Human Rights Law

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security.

Article 20: Right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

Although not legally binding, the UDHR forms the moral and legal foundation for modern human rights norms.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

Bangladesh ratified the ICCPR in 2000.

Article 6: Protects the right to life, strictly limiting when states may use lethal force.

Article 19 & 21: Guarantee freedom of expression and assembly.

The Gopalganj massacre constitute a violation of Article 6 if the deaths were a result of excessive, arbitrary, or unlawful force. ICCPR jurisprudence (e.g., Khashiyev v. Russia, 2005) affirms that states must investigate all suspicious deaths.

3.2 International Law on Use of Force

UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (1990)

Law enforcement may use firearms only in self-defense or defense of others against imminent threat of death.

Use of force must be proportionate and accountable.

Full transparency in cases of death or injury is required.

Failure to conduct autopsies and account for deaths in Gopalganj breaches these principles.

UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials

Requires that officials maintain integrity, refrain from torture or cruel treatment, and report abuses.

3.3 International Criminal Law and Crimes Against Humanity

-Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC)

Article 7: Crimes against humanity include:

-Murder

-Persecution

-Imprisonment

Other inhumane acts intentionally causing great suffering.

While Bangladesh is not a party to the Rome Statute, the UN Security Council can refer cases. Notably, the July 2024–25 massacres were described by OHCHR as “Meticulous and systematic” and “targeting political identity”, which fits within Article 7’s threshold for crimes against humanity.

Customary International Law

Even without ICC jurisdiction, customary international law obligates Bangladesh to prevent:

-Extrajudicial executions

-Arbitrary arrests

-Systematic persecution of political identity groups

3.4 Bangladesh Domestic Law

International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 (Amended 2025)

Originally focused on prosecuting 1971 war crimes, the 2025 amendment empowered the tribunal to try modern mass atrocities, especially those linked to political organizations.

Key provisions:

Section 3(2): Includes murder, persecution, and forced disappearance as crimes.

Section 5A (new): Authorizes investigation of any organization responsible for systematic violence.

The Gopalganj incident falls under its jurisdiction if proven systematic or politically motivated.

Bangladesh Constitution

Article 31: Right to protection of law.

Article 39: Freedom of speech and assembly.

The constitutional guarantees must align with Bangladesh’s treaty obligations, and the Gopalganj events appear to violate both.

4. Legal accountability & analysis

4.1 Right to Life and State Responsibility

The right to life is non-derogable, even in emergencies. Bangladesh is obliged to:

-Prevent unlawful killings.

-Investigate and prosecute violations.

-Provide remedies to victims’ families.

The deaths in Gopalganj, particularly absent autopsies, indicate a breach of these obligations.

4.2 Suppression of Assembly and Political Rights

Freedom of assembly is a cornerstone of democracy. Disrupting a peaceful rally and allowing private party militias to attack civilians is a gross violation. The state may not use paramilitary proxies to evade accountability.

4.3 So-called interim’s Legal Failures

Despite forming a fact-finding team:

-No murder charges filed.

-Detentions made under Special Powers Act, often used to suppress dissent.

-Delays in tribunal engagement show lack of political will.

4.4 Legal Remedies

ICT Act allows filing of cases by victims or the Attorney General.

UN bodies like OHCHR can open investigative missions.

Universal jurisdiction may allow cases to be filed in other states’ courts (e.g., Spain v. Pinochet precedent).

5. Way forward: Upholding international norms

5.1 Independent Judicial Inquiry

-Composed of retired judges, UN experts, and civil society.

-Empowered to subpoena evidence, interview security officials, and protect witnesses.

5.2 Autopsies and Forensic Transparency

-Immediate medical examination of deceased.

-Digital preservation of protest footage and chain-of-command analysis.

5.3 Activate International Tribunals

-Submit complaints to UNHRC, Special Rapporteurs on extrajudicial executions.

-Push for UN Security Council referral to ICC.

5.4 Civil Society and Documentation

-NGOs and journalists must be allowed free access.

-A public “truth archive” documenting July–August 2024–25 political killings are vital for transitional justice.

The Gopalganj Massacre of 16 July 2025 is a landmark in Bangladesh’s post-Awami era. The combination of political militancy, state complicity, and human rights violations illustrates the dangers of unchecked authoritarianism—even after formal regime change.

International law—especially under the ICCPR, UDHR, and customary international norms—provides clear prohibitions against the actions witnessed in Gopalganj. Bangladesh’s ICT Act (2025 amendment) further offers a rare, indigenous opportunity to ensure accountability.

However, unless these frameworks are implemented with integrity, urgency, and independence, the massacre will join a long list of unpunished atrocities. For victims and future generations, justice delayed is not just denied—it is erased.

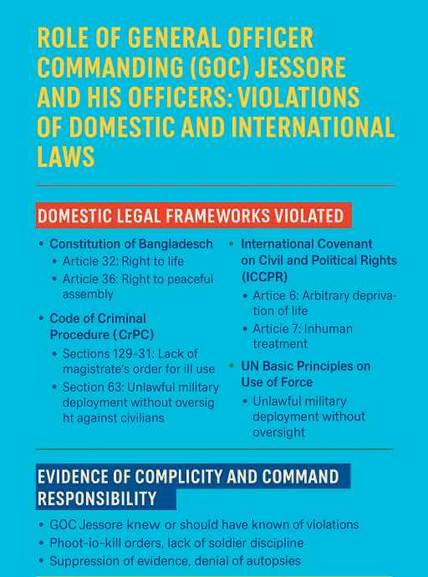

6. Role of the General Officer Commanding (GOC) Jessore and His Officers: Violations of Domestic and International Laws

6.1 Military Involvement in Civilian Policing

The Gopalganj Massacre on 16 July 2025 marked a grim example of what can go wrong when military authority is invoked to control civilian political dissent. One of the most controversial aspects of this incident was the direct operational involvement of the military, particularly the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Jessore Area—a region that encompasses Gopalganj under the jurisdiction of Bangladesh Army’s 55 Infantry Division. The GOC, a two-star general, along with subordinate commanding officers, reportedly coordinated the military presence and use of lethal force on unarmed civilians during the rally organized by the National Citizen Party (NCP).

Despite Bangladesh’s constitutional and legal provisions that civil administration shall be separate from the military, several witnesses, video evidence, and preliminary reports suggest that the GOC and his command structure were central to the disproportionate and fatal military response to the NCP gathering. This section analyzes how the Jessore Area Command violated both Bangladesh’s domestic laws and international legal obligations relating to the protection of civilians, lawful use of force, and state accountability. (1) Lieutenant Colonel ZM Mabruk, CO – 29 EB (Div Sp), BA-7643, 58 BMA L/C (2) Major General JM Emdadul Islam, General Officer Commanding (GOC), Jessore Cantonment, BA-4288 (3) Brigadier MD Mizanur Rahman, Commander, 88 Infantry Brigade, BA-5594, 37 BMA 10.

6.2 Domestic Legal Frameworks Violated by GOC Jessore and His Officers

6.2.1 The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

Article 26(2): Any law or action inconsistent with the fundamental rights is void.

Article 31: Guarantees the right to protection under law.

Article 32: Ensures the right to life and personal liberty.

Article 36: Freedom of movement and peaceful assembly.

The deployment of military personnel by the GOC in suppressing a lawful political assembly without prior civilian court authorization violates both Article 32 (right to life) and Article 36 (right to peaceful assembly). Eyewitness accounts and media footage showed uniformed military officers participating in operations were unarmed civilians were chased, beaten, and shot. The Army’s actions were neither approved through parliamentary order nor judicially sanctioned—thereby breaching the constitutional separation of powers.

Furthermore, under Article 7A of the Constitution, sedition includes any attempt to subvert the sovereignty of the people. By undermining citizens’ rights through unlawful military intervention, GOC Jessore may be liable under this provision if accountability is pursued in good faith.

6.2.2 Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and Army Involvement

Under Sections 129–131 of the CrPC, the use of armed forces is permitted only when law enforcement fails and only under a written magistrate’s order. No such order was presented or made public for the 16 July military action. This omission strongly indicates unlawful military deployment.

Moreover, the Army Act, 1952 governs conduct and jurisdiction of military personnel. Section 63 criminalizes any behavior prejudicial to good order or military discipline, including unauthorized aggression against civilians. No disciplinary proceedings have been reported against any officers involved, raising questions about military self-governance and opacity.

6.3 International Legal Standards Violated by the GOC and His Officers

6.3.1 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

As noted earlier, Bangladesh is a signatory to the ICCPR (2000). The ICCPR Article 6(1) reads: “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

By ordering or permitting use of lethal force without imminent threat, the GOC Jessore directly violated ICCPR Article 6, and Article 7, which prohibits torture or cruel, inhuman treatment.

6.3.2 The Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (UN, 1990)

Principle 9: Lethal force may only be used when strictly unavoidable to protect life.

Principle 12: In cases of death, a detailed report shall be submitted and investigated through an impartial body.

Principle 14: In situations of civilian protest, the use of military force must always be a last resort.

The deployment of combat-grade ammunition by army personnel against peaceful demonstrators without independent civilian oversight blatantly violates these standards. There is no indication that soldiers were under threat of imminent death when opening fire on the crowd.

6.3.3 Customary International Law and the Duty to Investigate

-Customary law, as recognized in the ICJ Statute, holds that all governments must:

-Investigate unlawful killings.

-Prosecute responsible agents.

-Compensate victims.

GOC Jessore’s apparent refusal to cooperate with civilian investigators, and the military’s internal refusal to subject officers to judicial oversight, contradict these principles and contribute to a culture of impunity.

6.4 Evidence of Complicity and Command Responsibility

6.4.1 Command Responsibility Doctrine

Under international humanitarian law and codified in Article 28 of the Rome Statute, military commanders are criminally responsible if:

-They knew or should have known that forces under their control were committing violations.

-They failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures to prevent or repress their commission.

In the Gopalganj context:

-Eyewitnesses and video recordings confirm military presence and fire on civilians.

-Victims were shot in the head and chest, indicating shoot-to-kill orders rather than crowd control tactics.

-Army personnel were deployed in military-grade vehicles, not riot control formats, signaling premeditated escalation.

-The GOC Jessore’s role in approving deployment, not calling off operations, and not initiating disciplinary hearings implies complicity under the doctrine of command responsibility.

6.4.2 Absence of Autopsies and Evidence Suppression

Reports from HRFB and family members allege:

-Immediate burial of victims without autopsies.

-Denial of medical documents and denial of access to bodies.

Such suppression may be interpreted as tampering with forensic evidence, a serious crime under both Bangladesh Penal Code and UN guidelines on extrajudicial executions (UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings, 2016).

6.5 Political and Strategic Implications of GOC Involvement

6.5.1 Militarization of Politics

Bangladesh’s political transitions have long been marred by military interventions, notably in 2007 and during transitions post-2024. The GOC’s involvement in Gopalganj signals a dangerous precedent: military suppression of democratic movements under the guise of national security. This blurs the line between defense and policing, and undermines democratic consolidation.

6.5.2 National and International Repercussions

The involvement of the military:

-Weakens civil-military balance.

-Delegitimizes the current administration’s post-Awami transparency pledges.

-Risks sanctions or travel bans by foreign governments.

-Undermines Bangladesh’s UN peacekeeping participation, as allegations of crimes against civilians violate the UN’s zero-tolerance policy on human rights abuses.

6.6 Recommendations for Accountability and Renovation

6.6.1 Civilian Oversight of Military Operations

-Establish an independent civil-military oversight board.

-Amend the CrPC to explicitly bar military deployment in political protests.

6.6.2 Public Judicial Inquiry

-Form a judicial commission empowered to summon army officers.

-Mandate military cooperation under Article 27 of the Army Act.

6.6.3 Inclusion in ICT Proceedings

Include Jessore GOC and senior officers in the formal International Crimes Tribunal docket.

Invoke command responsibility in formal charges.

6.6.4 International Monitoring

-Request UN OHCHR to dispatch fact-finding missions.

-File complaints to UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

6.7 Conclusion: Justice Demands Accountability at the Top

The events of 16 July 2025 are not merely acts of rogue aggression by isolated troops. They reflect a systemic militarization of civic space, enabled and coordinated by senior officers, notably the GOC Jessore, who must be held accountable. Upholding international and domestic law requires scrutiny, investigation, and judicial independence. Without this, the memory of Gopalganj’s dead will remain not only an unhealed wound but an ongoing threat to democracy in Bangladesh.

References

Amnesty International. (2025). Bangladesh: Gopalganj deaths must be independently investigated.

Bangladesh Army Act, 1952.

Bangladesh Constitution (Amended 2023).

Bangladesh Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC).

Human Rights Forum Bangladesh (HRFB). (2025, July). Statement on Military Involvement in Gopalganj.

International Committee of the Red Cross. (2020). Customary IHL Database.

International Criminal Court. (1998). Rome Statute.

OHCHR. (1990). Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

UN Human Rights Council. (2025). Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions: Bangladesh.

UNOHCHR. (2025). Mass Violence in Bangladesh: Preliminary Fact-Finding Report.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025). March to Gopalganj.