By Akash Mazumder

The global development discourse has long celebrated microfinance as a silver bullet for poverty alleviation. At the forefront of this narrative stands the Grameen Bank and its founder, Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus. Touted as a visionary, Yunus presented microcredit as an ethical alternative to exploitative lending, targeting the rural poor—particularly women. However, as critiques have emerged globally and from within Bangladesh, it is increasingly necessary to examine whether the model merely alleviates poverty—or capitalises on it. This article explores how poverty, in the context of Grameen Bank and the Yunus Center, has been transformed into a profitable enterprise under the guise of social business.

Microfinance to Mistrust: Yunus’s ethical dilemma in the poverty-baron scandal

Dr Muhammad Yunus: A cautionary note by eminent writer Ahmed Sofa

Yunus is using database to crush Awami League, says Sheikh Hasina

Sheikh Hasina reveals Yunus empire, built on ill-gotten money

The Rise of Grameen: A Humanitarian Promise

Established in 1983, the Grameen Bank was founded to deliver small loans to the poor without requiring collateral. With 97% of borrowers being women, the initiative promised empowerment, entrepreneurship, and economic freedom. Its success brought Muhammad Yunus international fame, culminating in the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize. Donors, international organisations, and Western governments flocked to support the microcredit. The Yunus Center emerged as the global hub of this vision, branding the idea of “social business” as a new frontier for capitalism with a conscience.

Microfinance and the Commodification of Poverty

As the microfinance industry grew, so did its contradictions. Critics argue that microfinance, including the Grameen Bank model, shifted from a humanitarian mission to a revenue-generating system:

- High-Interest Rates: Grameen Bank borrowers often face annualised interest rates exceeding 20–25%, significantly higher than traditional bank loans. Though justified as covering operational costs, such rates often trap borrowers in cycles of repayment.

- Group Lending and Peer Pressure: The use of group lending mechanisms forces poor women to guarantee each other’s loans. This peer pressure model has reportedly led to social ostracisation, mental health issues, and even suicides in extreme cases.

- Debt Overlap and Multiple Loans: Grameen’s success led to a flood of copycat microfinance institutions. Many borrowers take out multiple loans, often to repay older ones, spiralling into a debt trap reminiscent of loan-sharking, not liberation.

The Business Model of the Yunus Center

The Yunus Center functions as a branding and advocacy wing of the microcredit empire. While publicly committed to “social business,” its operations mirror corporate branding more than grassroots empowerment. Key criticisms include:

- Monetisation of Conferences and Consultancies: The Yunus Center organises global events, seminars, and leadership workshops that charge hefty fees, attracting development professionals and corporate leaders rather than the poor.

- Export of the Model as a Franchise: Instead of tailoring solutions to diverse local contexts, the Yunus Center promotes a universal blueprint of “Grameen-style” business. Nations are encouraged to replicate the model regardless of cultural, political, or economic differences.

- Nobel Branding and Political Capital: The Nobel laureate status of Yunus has been leveraged to gain political and economic influence globally, while critics within Bangladesh accuse the organization of bypassing democratic accountability under the shield of international prestige.

The Dark Side of Microcredit: Stories from the Ground

Numerous investigative reports and academic studies have revealed the human cost of microfinance:

- Over-Indebtedness: In regions of Bangladesh, especially in rural districts like Tangail, Nilphamari, and Jessore, microcredit has led to unsustainable debt burdens. Borrowers often sell assets, pull children out of school, or migrate for labour to service loans.

- Psychological Toll and Social Stigma: Women who default on loans are frequently shamed, excluded from community activities, or subjected to verbal and psychological abuse during group meetings.

- Token Empowerment: While loans are issued in women’s names, male family members often take control of the money, diluting the model’s claims of female empowerment.

From Development to Corporate Strategy

The Grameen conglomerate includes ventures with multinational corporations such as:

- Grameen Danone (with Groupe Danone)

- Grameen Veolia Water Ltd. (with Veolia)

- Grameenphone (with Telenor)

While portrayed as partnerships for good, these ventures have generated significant revenues with questionable reinvestment into poverty eradication. Critics argue that such joint ventures effectively turn the poor into consumers and micro-investors rather than beneficiaries of structural change.

How Grameen founder Muhammad Yunus fell from grace

Grameen Bank: a debt trap for the poor?

International Glorification, Domestic Criticism

Internationally, Muhammad Yunus is celebrated, with invitations to speak at the UN, Davos, and universities. But in Bangladesh, scepticism is growing:

- Accusations of Tax Irregularities and Fund Misuse: A Norwegian documentary in 2010 titled Caught in Micro Debt accused Yunus of diverting donor funds—allegations he has denied, but which ignited intense national scrutiny.

- Elitist Detachment: Critics point out that while Yunus travels in elite circles, he remains detached from the day-to-day realities of rural borrowers. His image as a saviour often overshadows the structural conditions that perpetuate poverty.

Poverty as a Perpetual Business Cycle

The Grameen model has been accused of keeping people just above starvation, ensuring they remain dependent borrowers. Unlike welfare programs or rights-based development that seek to structurally eliminate poverty, microfinance perpetuates a transactional relationship:

- No Focus on Structural Inequality: Landlessness, lack of access to education, climate vulnerability, and political disenfranchisement are ignored in favor of individual entrepreneurship.

- Repayment over Rights: The poor are seen not as citizens deserving justice but as clients expected to repay on time.

- Moral Economy of Neoliberalism: Microfinance aligns with neoliberal ideology that blames poverty on individual failure rather than systemic injustice. In this narrative, a poor woman failing to repay a loan becomes morally culpable, not the system that offered no alternative.

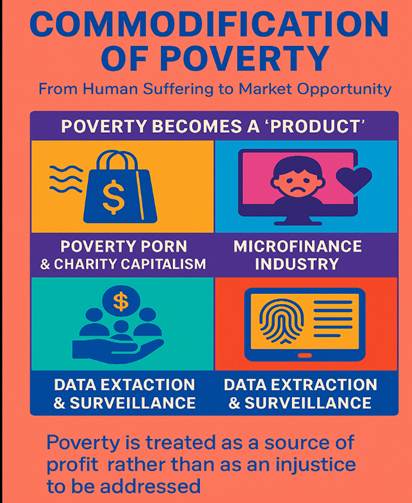

Commodification of Poverty: From Human Suffering to Market Opportunity

Poverty, historically understood as a condition of deprivation, has increasingly become commodified in the global capitalist system. This transformation has redefined the poor not as citizens deserving rights but as consumers, clients, data points, or even opportunities for profit. The commodification of poverty manifests through microfinance industries, charity-based marketing, global development aid, social entrepreneurship, and digital humanitarianism. This article critically unpacks the mechanisms and implications of commodifying poverty, with particular attention to South Asia and Bangladesh. Drawing from political economy, postcolonial critique, and neoliberalism studies, it explores how systems that once promised emancipation now profit from perpetual marginalisation.

Commodification is the process by which something that was not previously bought and sold becomes a good or service that is exchanged in the marketplace. When poverty becomes commodified, suffering itself becomes a resource to be managed, monetised, and even sold. Global development agencies, NGOs, multinational corporations, and philanthropic enterprises increasingly treat poverty not as a structural injustice to be eradicated but as a “market” of opportunity.

As sociologist Zygmunt Bauman noted, modernity’s obsession with economic efficiency has redefined even the most vulnerable human conditions into tradable assets. In this context, poverty is no longer merely a condition to be overcome—it is a site for profit.

The Globalisation of Poverty Markets

Aid as Industry

The international development sector is a multi-billion-dollar industry. Aid bureaucracies, consultancies, and global NGOs depend on the continued existence of poverty to justify operations. Many donors and institutions operate with performance indicators and metrics that prioritise quantifiable outcomes over long-term change. This leads to:

- Short-term solutions over structural reform

- Dependence on data to demonstrate ‘impact’

- Competitive funding that rewards storytelling rather than systemic work

The Role of Microfinance

The microfinance industry, often presented as an anti-poverty tool, has become a textbook example of commodification. Poor people—especially women—are turned into loan recipients who repay with interest, creating cash flows for MFIs and investors. Institutions like the Grameen Bank and others convert social capital into financial capital, turning collective poverty into scalable profit.

In Bangladesh and South Asia, microfinance does not address landlessness, political disenfranchisement, or labour exploitation. Instead, it monetises the condition of being poor through debt dependency and repayment regimes.

Media Spectacles of Suffering

Images of emaciated children, disaster victims, and slum dwellers are often used to mobilise donations in humanitarian campaigns. This “poverty porn” aesthetic reinforces the spectacle of suffering, enabling donors to feel morally superior while rarely engaging with the structural causes of poverty.

Corporate Charity and Brand Value

Companies increasingly integrate corporate social responsibility (CSR) to associate their brand with poverty alleviation. Examples include:

- Product-red campaigns: A portion of consumer spending is redirected to charity.

- Cause-based marketing: “Buy one, give one” models transform poverty into a sales pitch.

- Celebrity philanthropy: Figures like Bono and Bill Gates dominate the narrative, often sidelining local voices and epistemologies.

These efforts, while seemingly altruistic, often benefit corporate image more than systemic change.

Social Enterprises and the Myth of Win-Win

The rise of social business and impact investing has blurred the line between doing good and doing well financially. Pioneered by figures like Muhammad Yunus, social business claims to serve both the poor and investors. However, this model often:

- Promotes market-based solutions over democratic or state-led development

- Encourages individual responsibility rather than collective rights

- Treats poverty as a niche market (e.g., low-cost health, food, education, tech)

In effect, the poor are turned into data subjects, users, and consumers of products designed for their “upliftment,” but which often bypass root causes.

Digital Poverty: Data Extraction and Surveillance

With the digitisation of aid and welfare systems, poverty is now a source of valuable data. Biometric identification systems like India’s Aadhaar, mobile-based cash transfers, and AI-driven NGO platforms use the poor as test beds for digital technologies. This creates:

- Surveillance and control over marginalised populations

- Extraction of behavioural data to be sold or analysed

- Techno-solutionism, where poverty is framed as a software or platform problem

These mechanisms reduce the poor to data points within global information systems while enriching private tech firms and consultants.

Structural Violence Hidden Behind Entrepreneurial Narratives

The commodification of poverty hides structural violence. Neoliberal development shifts responsibility for poverty away from the state and onto the poor themselves, expecting them to become:

- Entrepreneurs

- Borrowers

- Financially literate

- Innovation adopters

But this ignores that poverty is produced and reproduced by political economy: land grabbing, labour exploitation, displacement, caste, gender inequality, and corruption. Commodification rewrites these injustices as “challenges” solvable through innovation and finance, not justice.

Bangladesh as a Case Study

Bangladesh exemplifies the commodification of poverty:

- NGO Capitalism: From BRAC to Grameen, NGOs have filled roles traditionally held by the state, turning poverty into a development enterprise.

- Foreign Aid Dependency: Billions in donor funds have supported programs that often fail to transfer power or build sustainable local economies.

- Urban Slum Markets: Informal settlements are sites for microenterprise, experimental sanitation models, and fintech trials—but rarely receive land rights or legal protections.

Even as the country celebrates its economic growth, inequality deepens, and poverty shifts from the rural to the urban, from absolute to structural, but still commodified.

Alternatives to the Poverty Market

If poverty is not a business but a consequence of injustice, alternatives must reframe development as rights-based rather than market-based. Recommendations include:

- Universal Basic Services (UBS): Public healthcare, education, and housing for all

- Redistributive Policies: Wealth and land redistribution, progressive taxation

- Decolonising Development: Centering indigenous knowledge, grassroots organisations, and local sovereignty

- Ethical Aid: Accountability to recipients, not just donors

- Community-Owned Finance: Models like self-help groups and community banks with collective ownership provide more equitable alternatives.

- Universal Social Protection: Basic income, health care, and education must be guaranteed as rights, not services to be purchased with microloans.

- Regulation and Transparency: Governments and global organisations must regulate microfinance institutions and demand transparent reporting of profits, interest rates, and borrower outcomes.

Poverty remains one of the greatest injustices of our time. Yet, under capitalism, it has become a source of profit—an industry, a brand, a data stream. The commodification of poverty may generate short-term solutions, but it risks normalising inequality, depoliticising suffering, and obstructing justice. Real transformation requires confronting the systems that produce poverty, not packaging it for sale. The Grameen Bank and Yunus Center, despite noble origins, risk becoming symbols of how poverty can be rebranded as opportunity, for those who profit from managing it. In a global economy eager for moral capitalism, the commodification of poverty under microfinance must be critically examined. Liberation cannot come from loans; it must come from structural transformation rooted in justice, rights, and equity, not just entrepreneurship.

References:

- Bateman, M. (2010). Why Doesn’t Microfinance Work? The Destructive Rise of Local Neoliberalism. Zed Books.

- Bateman, M. (2010). Why Doesn’t Microfinance Work? The Destructive Rise of Local Neoliberalism. Zed Books.

- Bauman, Z. (2007). Consuming Life. Polity Press.

- Cramer, C. (2014). The Political Economy of Microfinance. Development and Change, 45(3), 1–25.

- Documentary: Caught in Micro Debt (2010). NRK (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation).

- Kapoor, I. (2013). Celebrity Humanitarianism: The Ideology of Global Charity. Routledge.

- Karim, L. (2011). Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh. University of Minnesota Press.

- Karim, L. (2011). Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh. University of Minnesota Press.

- Moyo, D. (2009). Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Roy, A. (2010). Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the Making of Development. Routledge.

- Sinclair, H. (2012). Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic: How Microlending Lost Its Way and Betrayed the Poor. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Akash Mazumder: The writer can be reached at sbcukedu25@gmail.com