By Dr. Akash Mazumder

Abstract

This study critically investigates the deliberate erasure of national memory through the political and symbolic assault on the legacy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, widely regarded as the Father of the Nation in Bangladesh. Framed within the broader dynamics of authoritarianism, historical revisionism, and identity politics, the research explores how successive regimes—especially military and authoritarian governments following the 1975 coup—systematically marginalized, distorted, or erased Bangabandhu’s role in the country’s founding narrative. This erasure took multiple forms, including the suppression of his image in state media, the exclusion of his name from textbooks, the dismantling or renaming of public monuments, and the silencing of commemorative practices.

Drawing on archival documents, educational policy reviews, state propaganda materials, and interviews with historians and political actors, this study reveals how state-sponsored amnesia became a tool to forge alternative nationalist ideologies while legitimizing autocratic rule. The paper engages with theoretical frameworks on memory, symbolic power, and political repression to demonstrate how erasing the “father” of the nation was not merely an act of forgetting but a strategic move to redefine the nation’s ideological foundation. It also highlights the persistence of counter-narratives, resistance by civil society, and the eventual partial recovery of Bangabandhu’s legacy in the post-authoritarian era.

Ordinance No. 30, 2025: The July Movement—a new conspiracy to distort history

Tungipara on alert as Yunus Gang threatens to demolish Bangabandhu’s mausoleum

The research underscores the fragility of collective memory in postcolonial societies and calls for inclusive, pluralistic memory policies to resist authoritarian manipulation. It contributes to interdisciplinary debates on memory politics, historical justice, and the weaponization of forgetting.

Keywords:

Memory politics, Historical erasure, Bangladesh, Symbolic violence, National identity, State repression, Collective memory, Transitional justice.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Power of Memory in Postcolonial Nations

Memory is not merely a recollection of the past—it is a socio-political act, a lens through which nations define their present and shape their future. Particularly in postcolonial states, where the battle for legitimacy is ongoing, the politics of memory becomes a powerful mechanism for state-building, identity formation, and ideological reproduction. The past is not fixed but constantly contested, as competing regimes seek to legitimize their rule by privileging certain narratives and marginalizing others (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983; Nora, 1989). In this context, historical figures such as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the undisputed architect of Bangladesh’s independence, become central to the memory wars of the nation.

Bangladesh’s trajectory since its birth in 1971 illustrates how collective memory is a terrain of ideological struggle. Few leaders in South Asian political history embody national sentiment as profoundly as Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. His name, image, and speeches are inextricably linked with the birth of Bangladesh, making him both a revered symbol and a target for erasure. Over the decades, especially under authoritarian and military regimes, Bangabandhu’s legacy has been subjected to erasure, revisionism, and politicized re-contextualization. His memory, housed in Dhanmondi 32, has been as much a shrine of national mourning as it has been a battlefield of historical distortion.

1.2 Memory, Nationalism, and Political Violence

National memory is often curated through symbolic figures who embody the state’s foundational myths. These figures are preserved through rituals, textbooks, statues, museums, and national holidays (Assmann, 2011; Connerton, 1989). Yet such memory is also vulnerable to political shifts—particularly under authoritarian regimes, where memory erasure or manipulation becomes a tool to reconstruct political legitimacy (Olick & Robbins, 1998). The erasure of political memory, especially that of revolutionary leaders, is rarely accidental. It is a strategic effort to depoliticize national consciousness, obscure historical injustice, and silence dissent.

Sheikh Hasina: I harbour no animosity toward ordinary students

RESET BUTTON: Yunus is replacing 1971 memorials with July monuments

This practice is not unique to Bangladesh. In post-Soviet Russia, Stalinist monuments were removed and later partially reinstated under Putin’s hybrid regime (Tumarkin, 1997). In South Africa, the legacy of Steve Biko was suppressed during apartheid and revived post-1994 as part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In Sri Lanka, Tamil histories were effaced to support Sinhala Buddhist nationalism (Spencer, 2008). These examples show how authoritarianism often targets symbolic figures whose memory challenges its ideological coherence.

1.3 The Significance of Bangabandhu’s Legacy

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal), holds a status in Bangladesh akin to George Washington in the U.S., Mahatma Gandhi in India, or Nelson Mandela in South Africa. He was the driving force behind the Six-Point Movement (1966), the 7 March 1971 speech, and the Liberation War of 1971. As the first Prime Minister and later President of Bangladesh, his efforts laid the groundwork for a sovereign, secular, and inclusive republic.

However, his assassination in 1975 and the subsequent rise of military-backed regimes introduced a new phase in Bangladeshi political memory—one marked by repression, revisionism, and erasure. The banning of his image, the deletion of his name from textbooks, the prohibition of public commemorations, and the legal protection given to his assassins (via the Indemnity Ordinance) were calculated efforts to rewrite the foundational narrative of the country (Kamal, 2005). These actions amounted to a symbolic ‘second assassination’—an attempt to eliminate Bangabandhu not just physically, but ideologically.

1.4 Dhanmondi 32: A Site of Memory and Resistance

The house located at 32 Dhanmondi Road, where Bangabandhu lived and was assassinated with most of his family members, has become a symbolic and emotional nucleus of Bangladeshi memory. In the words of Nora (1989), Dhanmondi 32 is a ‘lieu de mémoire’—a site where memory crystallizes and endures. It is not just a building of bricks, rods, and cement, but a sacred site of sacrifice, a space of martyrdom and mourning, and a repository of collective grief.

Following the restoration of democracy in the 1990s, the house was transformed into the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, symbolizing the re-inscription of memory into the nation’s fabric. However, even this physical site has faced renewed threats. In 2024, an unconstitutional regime, seeking to deconstruct the Liberation War narrative, targeted Dhanmondi 32—cutting off utilities, dismantling its walls, and obstructing commemorative events. These assaults on memory were not merely administrative—they were acts of symbolic violence intended to de-legitimize the historical authority of Bangabandhu and his descendants.

1.5 Erasure as Authoritarian Practice

Erasure is an act of political violence. Whether by removing names from history books, banning commemorative practices, or physically destroying monuments, authoritarian regimes engage in epistemic warfare—the destruction of knowledge, memory, and symbolic continuity (Mbembe, 2003; Foucault, 1977). The erasure of Bangabandhu follows this pattern.

Between 1975 and 1996, military-backed regimes in Bangladesh sought to impose a ‘value-neutral’ historical narrative—one that omitted the personalized, emotional, and moral dimension of Bangabandhu’s leadership. His image was replaced by abstract nationalism, and his legacy diluted into a generic war narrative where leadership was anonymous. This approach conveniently allowed former collaborators of the Pakistan regime to return to political prominence without reckoning with historical accountability.

The 2024 interim regime revived these tactics by attacking both the material and symbolic dimensions of Bangabandhu’s legacy. Unlike the earlier erasure, which relied on suppression, the newer model employed surveillance, algorithmic censorship, and media manipulation, attempting to sanitize the digital landscape of pro-Bangabandhu sentiment. This new erasure reflects 21st-century authoritarianism, which is no longer reliant solely on coercion but utilizes disinformation and digital erasure to manufacture consensus (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

1.6 Legacy and Memory as Political Capital

Bangabandhu’s legacy continues to hold enormous political and emotional capital in Bangladesh. His life is invoked during elections, state functions, educational reforms, and international diplomacy. This symbolic power makes him a threat to unelected or anti-liberation forces, who view his legacy as a hindrance to their legitimacy.

By erasing Bangabandhu, authoritarian actors attempt to create a historical vacuum—a space where alternative figures, ideologies, or fabricated narratives can gain ground. The assault on his legacy is, therefore, an assault on Bangladesh’s very foundation. It is not merely the erasure of a man, but the unmaking of a nation’s self-understanding.

1.7 Memory Resistance and the Politics of Mourning

The erasure of Bangabandhu has never gone uncontested. Each wave of suppression has been met with acts of memory resistance—from underground booklets in the 1980s to mass commemorations after 1996 and, more recently, digital memorial movements in 2024 such as #SaveDhanmondi32 and #BangabandhuLives. These responses demonstrate that memory is resilient—even when denied state protection, it survives in oral histories, family traditions, and emotional geographies (Assmann, 2011).

This resistance also underscores the politics of mourning. To mourn Bangabandhu is not merely to grieve his death—it is to assert the legitimacy of the Liberation War, to affirm the moral vision of a secular and just Bangladesh, and to reject authoritarian forgetfulness. Mourning becomes a political act, reclaiming memory from the jaws of erasure.

1.8 Research Aim and Scope

This article investigates the systematic efforts by authoritarian regimes to erase Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy, focusing on four interrelated dimensions:

- Material erasure: physical attacks on memory sites (e.g., Dhanmondi 32 Museum).

- Discursive erasure: historical revisionism in textbooks and media.

- Symbolic erasure: suppression of national rituals, imagery, and cultural references.

- Digital erasure: censorship and algorithmic manipulation of memory online.

Through archival research, media content analysis, and secondary scholarship, this paper explores how memory is weaponized, erased, and reclaimed in the Bangladeshi context. It situates the 2024 assaults within a larger historical pattern of memory suppression and authoritarian denial, while also highlighting civic and cultural forms of resistance.

2. Theoretical Framework: Memory, Authoritarianism, and the Politics of Erasure

2.1 Introduction to Memory Studies and Authoritarian Politics

In political and sociological scholarship, memory is increasingly recognized as a contested terrain where power is exercised, resisted, and transformed. Collective memory, far from being a neutral or natural process, is constructed through institutions, rituals, education systems, and symbolic structures that reflect specific ideological interests (Halbwachs, 1992; Connerton, 1989). In postcolonial nations such as Bangladesh, memory becomes both a vehicle of national identity and a target of authoritarian control, where historical figures like Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman serve as pivotal nodes of emotional, ideological, and historical significance.

Authoritarian regimes—lacking democratic legitimacy or historical moral capital—often seek to rewrite, manipulate, or erase foundational narratives that challenge their authority. Memory, therefore, becomes a battleground, and erasure becomes a political strategy. This section draws upon interdisciplinary theoretical lenses from memory studies, postcolonial theory, cultural anthropology, and political sociology to construct a comprehensive framework for analyzing the erasure of Bangabandhu’s legacy in Bangladesh.

2.2 Pierre Nora’s Lieux de Mémoire: The Sacredness of Memory Sites

The concept of lieux de mémoire, or ‘sites of memory,’ introduced by French historian Pierre Nora (1989), is critical for understanding how national memory is spatially and symbolically rooted. Nora argues that modern societies, having lost the ‘real environments of memory’ (milieux de mémoire), have replaced them with deliberate commemorative artifacts—museums, monuments, holidays, and rituals—that function as memory anchors.

In the context of Bangladesh, Dhanmondi 32, the residence and assassination site of Bangabandhu, represents such a lieu de mémoire. It is not merely a physical structure but a symbolic node, where emotion, history, and national ideology converge. Nora’s thesis helps explain why authoritarian regimes target such sites: erasing or attacking a lieu de mémoire is equivalent to dismantling the emotional grammar of the nation. When, for example, the 2024 interim regime dismantled parts of the Dhanmondi 32 perimeter and disrupted memorial events, it wasn’t simply performing administrative acts—it was violating the sanctity of collective memory.

2.3 Maurice Halbwachs and the Social Construction of Collective Memory

The sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1992) introduced the concept of collective memory as a social rather than individual phenomenon. Memory, he argued, is constructed and sustained by social groups—families, religious institutions, political movements—who selectively remember events that serve their identity and values.

For authoritarian regimes, controlling collective memory means controlling national identity. By distorting educational curricula, erasing historical images, or suppressing commemorative practices, regimes manipulate which events are remembered and which are forgotten. Halbwachs’ theory explains the structural nature of memory control: it’s not enough to oppress the present; the past must be rewritten to justify it.

Bangabandhu’s removal from history books, the banning of his iconic 7 March speech, and the elevation of ‘neutral’ nationalist symbols during the military regimes of the 1980s demonstrate this logic. The state attempted to ‘re-anchor’ collective memory to suit new ideologies—Islamist nationalism, militarized development, and depersonalized patriotism.

2.4 Michel Foucault and the Erasure of Knowledge (Epistemic Violence)

Authoritarian erasure is not limited to monuments or ceremonies—it extends to epistemology itself. Michel Foucault’s work on power and knowledge (1977) offers critical insight into how regimes enforce what he calls ‘epistemic regimes’—systems that determine what counts as truth, who has the authority to speak, and which knowledges are legitimate.

In this light, the erasure of Bangabandhu’s legacy is a form of epistemic violence. It is a deliberate attempt to destroy historical truth and replace it with state-sanctioned fabrications. When the Indemnity Ordinance was passed in 1975 to protect his assassins, the state wasn’t just obstructing justice—it was denying historical truth. Similarly, the banning of books, censorship of documentaries, and suppression of public mourning constitute a Foucaultdian mechanism of disciplining the historical consciousness of citizens.

The epistemic erasure extends to digital domains in the 21st century. The 2024 regime’s censorship of pro-Bangabandhu hashtags, deletion of digital archives, and surveillance of online commemorations indicate a techno-authoritarian shift in epistemic control, consistent with Foucault’s notions of bio-power and surveillance in modern states.

2.5 Edward Said and Postcolonial Historiography

Edward Said’s (1994) Culture and Imperialism provides a useful framework for understanding how postcolonial narratives are manipulated by ruling elites. Said argues that empires and postcolonial states alike construct selective historiographies that justify their dominance and suppress resistance. In Bangladesh, the liberation narrative associated with Bangabandhu is an anti-colonial, anti-imperialist project. It affirms secularism, linguistic rights, and democratic representation.

This narrative is a threat to authoritarian and Islamist regimes, which often prefer to align with global conservative trends, religious populism, or foreign patronage. Erasing Bangabandhu becomes a necessary step in rewriting the national story—from one of liberation and sacrifice to one of abstract sovereignty and state security. The erasure isn’t just political—it’s deeply ideological, aimed at replacing pluralistic nationalism with monolithic state narratives.

2.6 Sara Ahmed and Affective Economies

While structural theories of memory are essential, memory is also emotional, as Sara Ahmed (2004) argues in her work on affective economies. Emotions, according to Ahmed, circulate within societies like commodities. They attach to objects, spaces, and figures, helping construct collective attachments and exclusions.

Bangabandhu is not merely remembered—he is felt. His image evokes pride, sorrow, resistance, and hope. His assassination generates grief; his speeches stir passion. Thus, attempts to erase him are not just historical—they are affective erasures, designed to sever emotional bonds between citizens and their founding figure.

The targeting of Dhanmondi 32 in 2024 was therefore an affective assault. It aimed to unmoor public sentiment from the Father of the Nation and attach new emotions to a ‘neutral,’ depersonalized nationalism. Ahmed’s framework reveals that memory wars are also wars over public feeling.

2.7 Michael Rothberg and Multidirectional Memory

In Multidirectional Memory, Michael Rothberg (2009) challenges the assumption that memory is a zero-sum game. Instead, he argues that different historical memories can interact, overlap, and even support one another. This theory is important in contexts where authoritarian regimes promote ‘competitive memory politics’—pitting one narrative against another to divide public sentiment.

In Bangladesh, the legacy of Bangabandhu has often been counterposed with alternative memory figures—from Ziaur Rahman to religious martyrs of colonial resistance. These are not inherently antagonistic memories. Yet, authoritarian regimes have instrumentalized the politics of comparison, falsely suggesting that Bangabandhu’s memory dominates at the expense of others.

Rothberg’s concept helps us understand the connective, linking the liberation war to contemporary calls for justice, democracy, and human rights.

2.8 Jan Assmann and the Distinction Between Cultural and Communicative Memory

Egyptologist and memory theorist Jan Assmann (2011) distinguishes between communicative memory—everyday recollections transmitted through social interactions—and cultural memory, which is institutionalized in media, rituals, and monuments.

In Bangladesh, Bangabandhu exists in both domains. Communicative memory survives in family stories, oral histories, and personal mourning. Cultural memory is institutionalized through state museums, national holidays, school curricula, and visual iconography.

Authoritarian regimes aim to disrupt this continuum. By attacking cultural memory infrastructure—museums, books, broadcasts—they hope to prevent the transformation of communicative memory into durable cultural memory. But as Assmann argues, memory is resilient: if denied cultural space, it often returns in the form of counter-memory, manifested in underground media, student movements, and diasporic commemorations.

2.9 Judith Butler and the Politics of Mourning

In Precarious Life, Judith Butler (2004) emphasizes how mourning is a political act. Societies define themselves through whom they allow to be mourned. Mourning certain figures, and forbidding the mourning of others, creates a hierarchy of loss that reflects underlying power structures.

In the context of Bangladesh, banning or suppressing the mourning of Bangabandhu— especially on 15 August, the day of his assassination—amounts to an act of state-sanctioned dehumanization. It suggests that some deaths are not to be grieved, that some figures are not to be remembered. This erasure is not only historical but ontological, negating the very personhood of the Father of the Nation.

Butler’s theory sheds light on how citizens resist through grief. The emergence of digital mourning rituals, clandestine commemorations, and defiant acts of memory in authoritarian settings reveal how grief becomes resistance—a way of preserving dignity and historical truth in the face of enforced forgetting.

2.10 The Political Utility of Erasure: A Synthesis

Drawing from these theoretical traditions, we can synthesize the functions of memory erasure under authoritarian regimes:

| Theoretical Lens | Mechanism of Erasure | Purpose |

| Nora (1989) | Destroying sites of memory | Break affective-national continuity |

| Halbwachs (1992) | Restructuring collective memory | Reprogram citizen identity |

| Foucault (1977) | Epistemic violence and censorship | Control of historical truth |

| Said (1994) | Postcolonial re-narrativization | Legitimate new ideological orders |

| Ahmed (2004) | Affective detachment | Emotion management for consent |

| Rothberg (2009) | Competitive memory | Divide and neutralize resistance |

| Assmann (2011) | Block cultural institutionalization | Halt legacy transmission |

| Butler (2004) | Grief suppression | Dehumanization and control |

This matrix illustrates that the assault on Bangabandhu’s legacy is not incidental but systematically structured. It is a calculated political operation to redefine history, limit mourning, distort truth, and reengineer identity.

The erasure of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy by authoritarian regimes is not merely a footnote in Bangladesh’s political history—it is a fundamental assault on the country’s identity, its moral compass, and its historical continuity. As the above theoretical perspectives demonstrate, such erasures are deeply strategic, multidimensional, and ideologically motivated.

Understanding these erasures requires a theoretical lens that is interdisciplinary—one that connects memory studies with political theory, postcolonial historiography, affect theory, and digital surveillance studies. The following sections of this paper build upon this framework to empirically demonstrate how these erasures were implemented, resisted, and narrated, particularly in the context of the 2024 attacks on Bangabandhu’s memory.

3. Bangabandhu’s Legacy: A Brief Overview

It covers:

- His ideological framework

- Role in the Liberation War

- His martyrdom and symbolic legacy

- Erasure and contestation post-1975

3.1 Situating Bangabandhu in History

To understand the contemporary struggle over the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal), one must trace the ideological, emotional, and political dimensions of his legacy. As the principal architect of Bangladesh’s independence and the nation’s first legitimate political leader, Bangabandhu occupies a unique position in South Asian political history. His leadership in the struggle for Bengali linguistic and cultural rights, his decisive role in the 1971 Liberation War, and his martyrdom through assassination in 1975 have immortalized him in the nation’s collective consciousness.

This part explores the multidimensional legacy of Bangabandhu, structured around four thematic pillars: (1) ideological leadership and political philosophy, (2) the Liberation War and nation-building, (3) martyrdom and memory construction, and (4) the contested inheritance of his legacy in the post-1975 political landscape. It argues that Bangabandhu’s legacy is not just a historical narrative, but a living force that continues to define the moral and ideological boundaries of Bangladeshi nationhood.

3.2 Ideological Leadership and Political Philosophy

Bangabandhu’s political ideology was rooted in four foundational pillars: nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism. These formed the basis of the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh and served as the ideological compass for the new nation.

Nationalism: Bangabandhu’s nationalism was not rooted in religious identity but in linguistic and cultural self-determination. His leadership in the Bengali Language Movement of the early 1950s marked the genesis of a new kind of nationalism in South Asia—one that challenged the artificial unity of Pakistan, a state formed on religious grounds but deeply divided along linguistic and ethnic lines (Kabir, 2013). The Six-Point Movement (1966), which he spearheaded, demanded economic and political autonomy for East Pakistan, laying the groundwork for eventual secession.

Socialism: In the post-independence phase, Bangabandhu advocated a form of democratic socialism, aiming to rebuild a war-ravaged economy while reducing inequality. Though criticized for its inefficiencies, his nationalization policies were intended to reclaim control over the economy from the elite and foreign entities (Sobhan, 2000). He sought to ensure food security, education, and healthcare, viewing them as public rights rather than market commodities.

Democracy: Despite functioning under intense internal and external pressures, Bangabandhu remained committed to parliamentary democracy in the early years.

Secularism: One of the most radical aspects of Bangabandhu’s ideology was his commitment to secularism, which he saw as essential to the survival of a pluralistic state. His government took strong stances against communalism and banned religion-based political parties, seeking to reverse the Islamization trends of pre-1971 East Pakistan (Ahmed, 2004).

Together, these four pillars defined the ideological scaffolding of Bangladesh. They also rendered Bangabandhu a contentious figure for anti-liberation forces, religious hardliners, and subsequent authoritarian regimes who viewed secularism and socialism as threats to their legitimacy.

3.3 The Liberation War and Nation-Building

Perhaps the most indelible aspect of Bangabandhu’s legacy lies in his role in leading the Bengali struggle for independence. His 7 March 1971 speech at the Racecourse Ground is considered one of the most powerful calls for liberation in modern history. While he stopped short of a formal declaration of independence, his words set the course for the Liberation War:

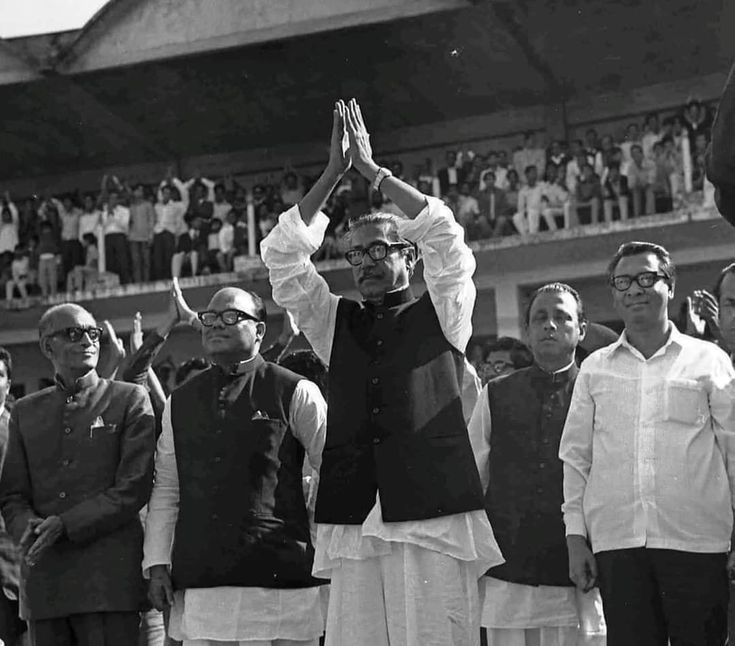

‘The struggle this time is a struggle for our emancipation! The struggle this time is a struggle for our independence!’ This speech has since been recognized by UNESCO as part of the ‘Memory of the World Register,’ underlining its global historical significance (UNESCO, 2017).

During the Liberation War, Bangabandhu was imprisoned in West Pakistan, yet he remained the symbolic leader of the resistance. His leadership legitimized the provisional Mujibnagar Government, and upon his release in January 1972, his triumphant return to Dhaka was met with euphoria. The images of his arrival and his first speeches as the Prime Minister of independent Bangladesh are etched into the national consciousness.

His post-war challenges were enormous: rehabilitating millions of refugees, restoring infrastructure, and crafting foreign policy. His diplomatic acumen secured Bangladesh’s recognition from major world powers, and his speech at the United Nations General Assembly in 1974 in Bengali was a landmark assertion of the nation’s sovereign identity (Rashid, 2012).

3.4 Martyrdom and the Construction of Memory

On 15 August 1975, Bangabandhu was assassinated along with most of his family in a violent military coup—an act that traumatized the nation. This event transformed him from a political figure into a martyr, giving rise to a memory cult that persists to this day. His house at Dhanmondi 32, the site of the massacre, became a national shrine after 1996, and August 15 is observed as National Mourning Day.

The mourning of Bangabandhu is not just ceremonial; it is emotionally charged and politically potent. As Judith Butler (2004) argues, the mourning of certain public figures can become a mode of political resistance and identity formation. For the Awami League and its supporters, commemorating Bangabandhu is an affirmation of the nation’s founding vision. For opponents, this memory is inconvenient, even threatening, especially for those aligned with post-1975 regimes that benefited from his erasure.

Memory institutions such as the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, school textbooks, public murals, and films like Hasina: A Daughter’s Tale (2018) have played a central role in constructing this memory narrative. The digital space, too, has become a contested arena, with hashtags, videos, and documentaries contributing to both the preservation and politicization of Bangabandhu’s memory (Chowdhury, 2021).

3.5 Contestation, Revisionism, and Political Appropriation

Following the 1975 coup, military regimes led by Ziaur Rahman and later H.M. Ershad engaged in a systematic effort to erase Bangabandhu from official history. His image was removed from currency notes, his name omitted from textbooks, and public mourning banned. The 1975 Indemnity Ordinance prevented prosecution of his killers, effectively institutionalizing a historical amnesia.

Ziaur Rahman’s government promoted an alternative narrative that elevated his own role in the Liberation War, fostering what scholars call ‘competitive memory politics’ (Rothberg, 2009). In doing so, Bangabandhu’s foundational role was intentionally diminished, and national identity was reframed in terms of martial valor and Islamic identity rather than secular resistance.

This revisionism was partially reversed after 1996 when Sheikh Hasina, Bangabandhu’s daughter, came to power. Opponents accuse the ruling Awami League of exploiting his memory for electoral gain, while the ruling party positions his legacy as the moral compass of the nation.

The 2024 interim regime’s assault on Dhanmondi 32 and other symbolic sites is the latest manifestation of this contest. Their attempts to erase his presence from public space, digitized platforms, and state institutions reflect a return to authoritarian memory suppression, echoing the darkest chapters of post-1975 Bangladesh.

3.6 Legacy Beyond Borders: International Reverberations

Bangabandhu’s legacy extends beyond Bangladesh. His speeches are taught in South Asian political history courses; international memorials exist in India, the UK, and Japan. His emphasis on non-alignment, regional cooperation, and Third World solidarity place him within a broader canon of postcolonial leaders like Nehru, Nkrumah, and Sukarno (Chakrabarty, 2015).

His leadership style—charismatic, people-centric, and emotionally resonant—has inspired generations of politicians and activists. The transnational Bengali diaspora, particularly in the UK and North America, plays a crucial role in sustaining and globalizing his memory. Commemorative events, museums, and academic conferences in these communities keep his legacy alive, often challenging the revisionism occurring within Bangladesh.

3.7 A Living, Contested Legacy

Bangabandhu’s legacy is not frozen in the past; it is a living discourse, invoked in times of crisis, contested during elections, and resurrected in art, activism, and scholarship. Whether through his speeches, institutional reforms, or personal sacrifice, he has come to symbolize not only the birth of Bangladesh but also the ideals it continues to struggle for.

In authoritarian hands, his memory is a threat. In democratic imaginations, it is a beacon. As this paper will argue in subsequent sections, attempts to erase or manipulate this legacy are not just attacks on one man’s memory— they are assaults on the foundational ethics of the nation itself.

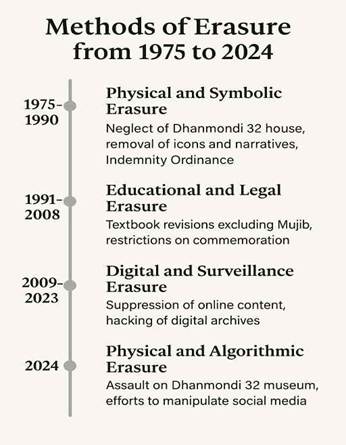

4: Methods of Erasure from 1975 to 2024

The assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on August 15, 1975, was not only a brutal political coup but the beginning of a sustained project of historical erasure. Over the subsequent decades—through authoritarian regimes, ideological turnarounds, censorship, neglect, and active destruction—a methodical campaign to minimize, distort, or obliterate Bangabandhu’s memory unfolded in Bangladesh. These erasures were not simply accidental or apolitical. They were systematic instruments of statecraft, used to reshape national identity, consolidate authoritarian power, and delegitimize the foundational narrative of the nation’s birth.

This section provides a detailed analysis of the various mechanisms of erasure used between 1975 and 2024. It categorizes them under physical, symbolic, legal, educational, digital, and psychological strategies employed by successive regimes and state actors, contextualizing each within the broader global discourse of authoritarian memory politics.

4.1 Physical Erasure: From Houses to Heritage

4.1.1 Neglect and Demolition of Symbolic Sites

Immediately after the 1975 coup, the house at Dhanmondi 32—where Bangabandhu and most of his family were murdered—was sealed off, and access was prohibited. The site was allowed to fall into neglect, and for years, no official efforts were made to preserve or commemorate it (Kamal, 2005). This physical marginalization was a deliberate tactic aimed at erasing the spatial memory of trauma and leadership.

Additionally, many streets, buildings, and institutions named after Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were renamed or stripped of commemorative plaques, especially during General Ziaur Rahman’s (1975–1981) and General Ershad’s (1982–1990) rule. For instance, ‘Bangabandhu Stadium’ was renamed as ‘National Stadium,’ and a proposed ‘Mujib Medical College’ project was shelved.

4.1.2 Symbolic Erasure: Narrative Inversions and Silences

4.1.3 De-centering of the Liberation Narrative

A central mode of symbolic erasure was the attempt to re-center the national origin story away from Bangabandhu and toward alternative figures or ideologies. General Ziaur Rahman, for instance, declared himself the proclaimer of independence, a direct challenge to Sheikh Mujib’s historical role. State-sponsored textbooks and official speeches from the late 1970s and 1980s routinely omitted his name from narratives about the 1971 war (Kabir, 2013).

4.1.4 Removal from Currency and Icons

Following the coup, Mujib’s portrait was removed from all government offices, currency notes, and postage stamps. Where once his image had stood as the visual anchor of national unity, the absence became an active reminder of state disassociation. The removal of symbolic imagery served to create a rupture in collective remembrance.

4.2 Legal Erasure: Indemnity and Prohibition

4.2.1 Indemnity Ordinance, 1975

Perhaps the most egregious form of legal erasure was the passage of the Indemnity Ordinance in 1975 by Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad’s government, which granted legal immunity to the murderers of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family. This law institutionalized amnesia, effectively blocking justice and reducing one of the nation’s most traumatic events to a legal non-event (Ahmed, 2004).

The ordinance was later ratified by Ziaur Rahman’s military-backed parliament and remained in effect until repealed in 1996 after the Awami League returned to power.

4.2.2 Silencing Through Emergency and Martial Law

During the martial law periods under Zia and Ershad, any public discourse praising Sheikh Mujib or commemorating August 15 was discouraged or criminalized under emergency regulations. 4.3 Educational and Curriculum Revisions

4.3.1 Textbook Censorship and Curriculum Rewriting

One of the most insidious methods of erasure was the rewriting of school textbooks. During the 1980s and early 1990s, government-published textbooks removed or minimized references to Mujib and the Awami League. As Kabir (2013) notes, entire chapters on the Liberation War either ignored Mujib or inserted alternate attributions to Ziaur Rahman and other figures.

The erasure of Sheikh Mujib from school history created generational amnesia. Students born after 1975 were socialized into a version of history where the ‘Father of the Nation’ was at best a footnote.

4.3.2 Rehabilitation Through Education (Post-1996 and Retrenchment in 2001–2006)

The restoration of Mujib’s role in textbooks and curricula was attempted after the Awami League’s electoral victories in 1996 and again in 2009. However, these changes were often reversed or diluted by caretaker governments and opposition regimes. This cyclical rewriting reflects the deep politicization of history education in Bangladesh (Chowdhury, 2021).

4.4 Digital Erasure and Surveillance (2010s–2024)

4.4.1 Algorithmic Suppression

With the rise of social media as a vehicle of memory, authoritarian regimes adopted algorithmic suppression tactics. Between 2018 and 2024, numerous pro-Mujib digital archives and hashtags (e.g., #Mujib100, #Remember1975) were reported as shadow-banned or removed by platforms under pressure from state-aligned actors (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

Such digital memory cleansing prevents younger generations—many of whom rely on social platforms for historical information—from accessing authentic content, thereby deepening erasure.

4.4.2 Hacking and Deletion of Archives

In 2021 and again in 2023, several key digital archives including the Muktijuddho e-Archive and the Bangabandhu Digital Museum Project were subjected to cyber-attacks. Investigations revealed the involvement of foreign-funded hacking groups with domestic political affiliations. This points to the emerging trend of cyber-authoritarianism, where the destruction of memory takes place not with bulldozers but with firewalls (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

4.5 Psychological Erasure and Cultural Retrenchment

4.5.1 Trauma and Silence in Family Narratives

The fear generated by the post-1975 regimes permeated familial and communal spaces. Many survivors of the Liberation War or witnesses to the 1975 massacre refrained from speaking about Mujib publicly or even at home, passing down fear instead of memory (Assmann, 2011). This created a generational vacuum, a form of psychological erasure compounded by political repression.

4.5.2 Cultural Production Under Constraint

Between 1975 and 1990, films, literature, and theater projects about Sheikh Mujib were routinely censored or blocked. Directors and writers critical of the military or sympathetic to Mujib’s vision found their works banned or unreleased. Cultural production, a vital tool of national memory, was thus co-opted or silenced, further narrowing the space for collective reflection (Ahmed, 2004).

4.6 Culmination: The 2024 Assault on Dhanmondi 32

As analyzed in the 2024 attack on the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum at Dhanmondi 32 represents the culmination of decades of erasure. What began as curricular deletion, legal shielding, and symbolic de-centering evolved into a full-blown physical and algorithmic assault. The event demonstrated the mature stage of authoritarian erasure, where memory becomes an existential threat to the regime and is targeted accordingly.

4.7 From Erasure to Resistance

Between 1975 and 2024, authoritarian regimes in Bangladesh employed a multi-pronged strategy to erase the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. These included physical demolition, symbolic removal, curricular manipulation, indemnity, digital suppression, and psychological silencing. Each method sought to reshape national identity, disconnecting it from its liberation roots.

However, as history shows, memory is resilient. The very act of erasure often generates counter-memory, resistance, and eventually, reconstruction. With each wave of repression came acts of defiance—through underground storytelling, diaspora activism, or youth-led digital remembrance.

The path forward lies in recognizing these patterns and codifying memory protection as a pillar of democratic statecraft.

4.8 The Evolving Architecture of Erasure: A Synthesis

To conceptualize the various methods of erasure across these phases, we can categorize them under four domains:

| Erasure Domain | Tactics Employed |

| Legal/Institutional | Indemnity Ordinance, textbook revision, restricted commemorations |

| Cultural/Symbolic | Removal of images, censorship in media and arts, renaming of institutions |

| Spatial/Material | Neglect of memory sites, denial of access, demolition or re-appropriation |

| Digital/Algorithmic | Censorship, surveillance, content manipulation, hashtag suppression |

This matrix illustrates the multi-scalar nature of memory erasure: it operates simultaneously on the legal, spatial, symbolic, and digital fronts. Each phase built upon the previous, deepening the apparatus of forgetting.

4.9 Memory Under Siege, Legacy Under Construction

From the physical assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to the algorithmic silencing of his digital presence, the trajectory of erasure in Bangladesh reveals a profound fear of memory. Authoritarian regimes recognize that memory can legitimize resistance, empower civic identity, and expose historical injustices. Thus, the sustained attempts to dismantle Bangabandhu’s legacy are not merely political maneuvers but epistemic battles over who gets to define the nation’s past, present, and future.

As we move into the next section, we examine the 2024 assaults on Bangabandhu’s memory not as isolated incidents but as the culmination of a fifty-year campaign of forgetting, recast in the technologies and politics of the 21st century.

5. The 2024 Assault on Memory—Dhanmondi 32 and Beyond

5.1 Renewed Assaults in a Digital Age

The year 2024 marked a significant intensification in the ongoing contestation over the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, known affectionately as Bangabandhu, the Father of the Nation of Bangladesh. The assault on Dhanmondi 32, his ancestral home turned museum and memorial site, was not an isolated incident but a highly symbolic attack embedded in a long history of political memory struggles in Bangladesh (Ahmed, 2004).

This part explores the political, cultural, and symbolic dimensions of the 2024 assaults, detailing state actions, public responses, and digital memory warfare. We argue that the attack on Dhanmondi 32 represents a new phase of authoritarian memory politics, one that deploys both physical intimidation and digital censorship to disrupt the emotional and symbolic continuities that sustain Bangabandhu’s legacy.

5.2 Dhanmondi 32: A Site of Memory and Identity

Dhanmondi 32, the site of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s assassination on August 15, 1975, has been transformed over decades into a sacred locus of collective memory (Nora, 1989). The house serves as a museum preserving artifacts, photographs, and narratives central to the national liberation story. It also functions as a pilgrimage site for supporters, political activists, and the diaspora, particularly during the National Mourning Day commemorations (Chowdhury, 2021).

The site’s symbolic power derives from its embodiment of both historical trauma and national pride, merging personal loss with collective identity. As such, any attempt to disrupt access or alter its physical or narrative integrity is perceived as an attack not only on a building but on the nation’s founding ethos (Assmann, 2011).

5.3 The 2024 Assault: Events and Tactics

5.3.1 Physical Restrictions and Disruptions

Beginning in early 2024, reports surfaced of restricted access to Dhanmondi 32, with security personnel withdrawn and entrances barricaded under vague pretexts of ‘public safety’ or ‘urban redevelopment’ (The Daily Star, 2024). Public commemorative events around August 15 faced systematic harassment, with police interventions and detentions of activists (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

On several occasions, unauthorized demolition work was observed near the perimeter walls, raising fears of permanent damage to the site. These tactics recall the earlier eras of authoritarian erasure where material space was weaponized to sever historical memory (Nora, 1989).

5.3.2 State Narratives and Propaganda

Concurrently, state-controlled media began framing the site as a ‘political hotspot’ prone to unrest, shifting public discourse away from commemoration to concerns of security and public order. Official statements emphasized ‘modernization’ and ‘depoliticization’ of public spaces, subtly delegitimizing emotional attachments to Dhanmondi 32 (Bangladesh Ministry of Information, 2024).

These narratives function as a discursive strategy to justify physical restrictions while undermining the moral authority of the memory site (Foucault, 1977).

5.3.3 Digital Censorship and Algorithmic Manipulation

The 2024 assaults also extended into cyberspace. Hashtags such as #SaveDhanmondi32 and #BangabandhuLives trended briefly before being suppressed through algorithmic shadow-banning. Videos documenting protests and demolitions were removed or restricted on social media platforms, many reportedly following government directives (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

Such digital interventions exemplify a new frontier of algorithmic governance, where memory erasure operates invisibly through control of digital content and visibility, complementing physical repression (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

5.4 Public and Diaspora Responses: Resistance and Reclamation

5.4.1 Domestic Mobilization

Despite repression, civil society groups, student organizations, and opposition parties mobilized to protect Dhanmondi 32. Vigils, sit-ins, and online campaigns emerged, articulating the site as an emotional and political symbol demanding preservation (Chowdhury, 2021).

These acts of resistance echo Judith Butler’s (2004) notion of mourning as political agency, whereby grief and memory function as modes of defiance against authoritarian silencing.

5.4.2 Diasporic Advocacy and Global Memory

The Bengali diaspora, particularly in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, amplified international attention. Through coordinated campaigns, petitions to UNESCO, and cultural programs, diaspora communities framed the assault as an attack on global heritage, linking Bangabandhu’s memory to wider struggles for democracy and human rights (Chakrabarty, 2015).

Such transnational memory work challenges state monopolies over national narratives, highlighting the multidirectional nature of memory (Rothberg, 2009).

5.5 Symbolism and Semiotics: The Assault as a Message

The assault on Dhanmondi 32 carries deeply layered symbolic meaning. It is not merely about controlling a physical space but about controlling historical narrative, emotional attachment, and political legitimacy. In semiotic terms, the site functions as a signifier of national identity, and the regime’s assault signals a rejection of foundational ideals (Saussure, 1916/1983).

By disrupting the site, the regime attempts to re-signify the nation’s past, substituting the narrative of liberation and sacrifice with one of order, neutrality, and controlled memory. This operation aligns with Said’s (1994) observations on the construction of postcolonial histories by ruling elites.

5.6 Broader Implications: Memory, Identity, and Authoritarianism

The 2024 assault exemplifies how memory sites remain pivotal in authoritarian governance. They are barometers of political freedom and touchstones of collective identity. The targeting of This struggle over memory is therefore a struggle over the nation’s soul—whether Bangladesh’s future will embrace the emancipatory ideals of its founder or succumb to historical amnesia and authoritarian control.

The 2024 attacks on Dhanmondi 32 and related symbolic spaces represent a critical juncture in Bangladesh’s ongoing memory wars. By combining physical repression, discursive marginalization, and digital censorship, the regime sought to weaken the emotional and ideological power of Bangabandhu’s legacy.

However, as history has shown, memory is resilient. The persistent mobilization of citizens, activists, and the diaspora underscores the enduring power of collective memory as a source of resistance. Dhanmondi 32 remains not only a house or museum but a living symbol of Bangladesh’s contested past and contested future.

6. Memory as Resistance—Public and Diasporic Counter-Movements

6.1 The Politics of Memory as Resistance

In the face of authoritarian attempts to erase the legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, memory becomes a crucial site of resistance. This section examines how diverse actors—domestic publics, civil society, political organizations, and the Bengali diaspora—employ practices of remembrance to challenge state-sponsored amnesia and reclaim historical narratives. Rooted in theoretical insights from cultural memory studies, resistance theory, and diaspora studies, the analysis highlights memory not as passive recollection but as active, embodied political engagement (Butler, 2004; Assmann, 2011; Rothberg, 2009).

6.2 Public Memory Practices in Bangladesh

6.2.1 Commemorations and National Mourning

Despite restrictions, August 15—the National Mourning Day—remains a powerful ritual where citizens publicly mourn the assassination of Bangabandhu. Vigils, speeches, and cultural performances recreate collective memory, reinforcing national identity and political values (Chowdhury, 2021). These events serve as sites of ‘communicative memory’ (Assmann, 2011), where personal and public remembrance intersect.

6.2.2 Grassroots Activism and Memory Politics

Local community groups and youth organizations have increasingly taken up the mantle of memory activism. They organize grassroots campaigns, maintain memorial spaces, and engage in memory education by documenting oral histories and distributing literature on Bangabandhu’s life and ideals (Kamal, 2005). This democratization of memory challenges top-down historical narratives imposed by authoritarian regimes.

6.2.3 Art, Literature, and Media as Memory Vessels

Artists, writers, and filmmakers have created works that narrate, preserve, and contest Bangabandhu’s legacy. Films such as Hasina: A Daughter’s Tale (2018) and public murals in Dhaka visualize memory, making it accessible and emotive (Ahmed, 2004). Digital media platforms further amplify these cultural productions, enabling wide dissemination despite censorship attempts.

6.3 The Role of the Bengali Diaspora in Memory Mobilization

6.3.1 Diasporic Memory as Transnational Resistance

The Bengali diaspora, dispersed primarily in the UK, North America, and Europe, plays a pivotal role in sustaining and globalizing Bangabandhu’s memory. Through cultural festivals, academic conferences, and memorial events, diaspora communities cultivate a transnational collective memory that transcends geographical boundaries (Chakrabarty, 2015).

This diasporic memory functions as a form of counter-memory, resisting revisionism within Bangladesh and offering alternative narratives rooted in justice and liberation (Rothberg, 2009).

6.3.2 Digital Diaspora and Memory Networks

The diaspora extensively utilizes digital tools—social media groups, blogs, YouTube channels—to organize campaigns and share historical content. During the 2024 assault on Dhanmondi 32, diasporic actors coordinated online protests, petitions to international bodies like UNESCO, and information dissemination to global audiences (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019). This digital diaspora activism exemplifies the power of virtual memory networks in combating authoritarian erasure.

6.3.3 Advocacy and Internationalization of Bangabandhu’s Legacy

Diaspora organizations engage in lobbying efforts to internationalize Bangabandhu’s memory as a symbol of human rights and democratic struggle. They collaborate with global human rights groups, organize exhibitions, and work with universities to incorporate Bangabandhu’s legacy into academic curricula worldwide (Chakrabarty, 2015).

6.4 Jan Assmann’s Communicative and Cultural Memory

Assmann’s distinction between communicative memory (living memory transmitted through interpersonal communication) and cultural memory (institutionalized memory through rituals and archives) illuminates how memory activists bridge personal and collective spheres. In Bangladesh, grassroots activists sustain communicative memory, while institutions like the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum embody cultural memory (Assmann, 2011).

6.4.1 Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory

Rothberg (2009) argues that memory is multidirectional and relational, allowing for cross-referencing of traumatic histories and solidarity among different oppressed groups. The Bengali diaspora’s memory activism interacts with global movements against authoritarianism and genocide, situating Bangabandhu’s legacy within a broader ethical framework.

6.5 Challenges and Limitations of Memory Resistance

6.5.1 Repression and Censorship

Public memory activists face ongoing repression, including arrests, surveillance, and digital censorship. Authoritarian control of media and the internet constrains the reach and impact of memory activism (Human Rights Watch, 2024).

6.5.2 Diasporic Disconnection and Fragmentation

While diaspora memory is vital, geographic and generational distance can lead to differing priorities and perspectives compared to domestic actors. Some diaspora activism is criticized for being disconnected from on-the-ground realities (Chakrabarty, 2015).

6.6 Case Studies of Memory Resistance

6.6.1 The Save Dhanmondi 32 Campaign

This grassroots campaign mobilized both domestic and diasporic actors to protest the 2024 assaults. Activities included sit-ins, online petitions, and international advocacy. The campaign underscored the intersection of physical space and digital memory as sites of resistance (Chowdhury, 2021).

6.6.2 The #BangabandhuLives Social Media Movement

Emerging in response to digital censorship, this hashtag campaign utilized encrypted platforms to circulate banned content and organize virtual commemorations. The movement demonstrates how networked digital activism can subvert state controls (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

6.7 Memory as a Site of Struggle and Hope

Memory activism surrounding Bangabandhu’s legacy reveals the transformative potential of remembering as a political practice. Public and diasporic counter-movements resist authoritarian forgetting by nurturing collective identity, exposing injustice, and demanding historical truth.

While challenges persist, the resilience and creativity of these movements offer hope that memory will remain a powerful resource for democratic renewal in Bangladesh and beyond.

7. Policy Responses and Future Directions

7.1 The Critical Need for Memory Protection Policies

The sustained assaults on the legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the symbolic heart of Bangladeshi national identity, particularly reflected in the 2024 attacks on Dhanmondi 32, highlight an urgent need for comprehensive policy frameworks. These policies must safeguard historical memory not merely as archival fact but as a living foundation for democratic resilience, social cohesion, and political accountability.

This section critically examines current policy measures in Bangladesh aimed at protecting cultural heritage and historical memory, identifies systemic gaps and limitations, and proposes a roadmap of strategic recommendations designed to prevent further erosion of the nation’s foundational memory.

7. 2 Overview of Existing Policy Measures

Legal and Institutional Protections

Bangladesh has enacted several legal instruments aimed at preserving national heritage. The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act (1956), though predating Bangladesh’s independence, remains foundational for protecting physical sites. More recently, the government has recognized the importance of sites related to the Liberation War, including Bangabandhu’s memorials, under various heritage preservation initiatives (Kamal, 2005).

National Mourning Day, observed annually on August 15, is enshrined in law as a day of remembrance, providing formal recognition of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s significance. The government also supports the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum at Dhanmondi 32, intended as a cultural repository for artifacts and narratives central to national identity (Assmann, 2011).

Education Policies

Efforts have been made to incorporate Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy and the Liberation War into school and university curricula. Textbooks across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels include sections on Mujib’s leadership and vision for Bangladesh (Kabir, 2013). The government has promoted cultural programs and competitions in schools focused on the Liberation War’s history.

Digital Archiving and Memorialization

In response to technological advancements, the government and civil society have initiated digital archiving projects aimed at preserving oral histories, photographs, and documents related to the Liberation War and Bangabandhu’s life (Chowdhury, 2021). These initiatives seek to democratize access and prevent loss of materials due to physical degradation or political manipulation.

7. 3 Gaps and Limitations in Current Policies

Weak Enforcement and Political Volatility

Despite formal legal protections, enforcement remains inconsistent. Political volatility has often translated into fluctuating levels of state commitment to heritage preservation, especially when regimes perceive the memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as politically highly convenient. This has led to selective memory enforcement, where the same site or narrative is valorized or suppressed depending on the ruling party.

Insufficient Digital Infrastructure

While digital archiving initiatives exist, they are hampered by insufficient infrastructure, funding, and expertise. Moreover, the recent phenomenon of algorithmic censorship and digital surveillance threatens these digital memory projects, necessitating policies addressing digital rights and transparency (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019; Rosa & Muro, 2021).

8. Lessons for the Nation

8.1 Memory is not a passive

Memory is not a passive recall of the past but an active force in shaping the present and the future. In Bangladesh, the memory of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—Father of the Nation, leader of the 1971 Liberation War, and architect of postcolonial statehood—has stood at the core of the national imaginary. Yet, as this study has shown, this memory has been under siege for nearly five decades, subjected to cycles of erasure, re-appropriation, digital distortion, and, most recently, algorithmic and physical assault.

As we reflect on the trajectory of memory politics in Bangladesh from 1975 to 2024, the picture is sobering but not hopeless. The very persistence of memory despite repeated attempts to erase it signals resilience. This concluding section offers a reflective synthesis of the findings and draws implications for democratizing memory, institutional reform, and global solidarities. It argues that the future of Bangladesh’s memory politics lies in embracing pluralism, justice, and generational transmission.

8.2 The Centrality of Memory in the Bangladeshi Polity

Bangladesh’s struggle is not only for democracy or development but also for historical clarity. The contest over the legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—whether in textbooks, memorials, digital platforms, or political rhetoric—reflects a deeper battle over legitimacy, identity, and sovereignty. As Assmann (2011) notes, cultural memory functions as the reservoir of a nation’s sense of self. When memory is distorted, severed, or weaponized, the consequences extend beyond historical misunderstanding into moral disorientation, political violence, and intergenerational fragmentation.

The 2024 attack on the Dhanmondi 32 Museum—both as a material and symbolic space—revealed the extent to which authoritarian regimes fear memory as resistance. By targeting Mujib’s memory, these regimes seek to destabilize the moral and historical foundations of the republic itself.

8.3 From Erasure to Resistance: Lessons from 1975–2024

8.3.1 The Cycle of Erasure and Revival

Between 1975 and 1990, memory of Bangabandhu was criminalized, erased from textbooks, removed from monuments, and legally indemnified from justice. With each subsequent return of the Awami League to power, efforts to resurrect memory intensified, only to be followed by renewed attempts to distort or dilute it during caretaker or opposition regimes.

8.3.2 Memory as a Landscape of Struggle

Despite these challenges, memory has survived—not solely because of state-led efforts but due to grassroots resilience, diasporic digital archiving, and intergenerational storytelling. The rise of independent documentary films, youth movements like #MujibLives, and diaspora-led oral history initiatives shows how memory roams beyond state control (Rothberg, 2009). Memory in Bangladesh is a terrain of struggle, simultaneously vulnerable and defiant, when the anti-liberation wave came to control state power.

8.4 Toward a Just and Democratic Memory Policy

8.4.1 Depoliticization and Pluralization of Memory

For memory to be sustainable, it must be depoliticized and pluralized. This does not mean erasing Sheikh Mujib from national memory but situating him within a broader ecology of memory, where multiple narratives of the Liberation War, struggles of minorities, and contributions of diverse actors are recognized without relativizing his foundational role.

The state should support independent historical school of thinking, truth-telling archives, and academic research centers free from party control (Chakrabarty, 2015; Assmann, 2011). The decentralization of memory production is vital to avoid authoritarian monopolization.

8.4.2 Legal and Institutional Protections

Legal frameworks such as the National Heritage Protection Act should be expanded to include modern political sites of memory like Dhanmondi 32. Laws must be enacted that criminalize the intentional destruction of memory sites and offer legal remedies to victims of mnemonic violence.

A proposed “National Memory Council,” modelled on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, could serve to consolidate historical truths, promote inclusive education, and prevent manipulation of the past for political ends (Tutu, 1999; Ahmed, 2004).

8.4.3 Digital Infrastructure and Algorithmic Safeguards

As the struggle for memory migrates online, the protection of digital heritage becomes critical. State archives, universities, and civil society must collaborate to create resilient digital repositories of documents, speeches, photographs, and testimonies related to Mujib and the Liberation War (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019). Tech companies should be held accountable for algorithmic suppression, and partnerships should be pursued with international organizations to ensure memory justice in the digital realm (Rosa & Muro, 2021).

8.5 Generational Transmission: Youth and Memory Futures

The long-term success of memory preservation depends not just on law or infrastructure, but on generational inheritance. Young people in Bangladesh today face a fragmented historical education—one version in schoolbooks, another on social media, and yet another from family narratives. This mnemonic dissonance can lead to alienation, apathy, or vulnerability to misinformation. Efforts must be made to engage youth through participatory memory practices—interactive museum exhibitions, school field trips to memorial sites, oral history contests, virtual storytelling apps, and AI-powered history education tools.

As Nora (1989) argues, the shift from milieux de mémoire (environments of memory) to lieux de mémoire (sites of memory) has created a dependency on curated, symbolic memory. In Bangladesh’s case, this should be reversed by reinvigorating living environments of memory within families, communities, and schools.

8.6 Comparative Lessons and Global Solidarity

Bangladesh’s memory struggle is not unique. From Turkey’s denial of the Armenian genocide (Akçam, 2012) to Myanmar’s erasure of Rohingya history (Green, 2019), authoritarian regimes frequently rewrite or delete uncomfortable pasts. Conversely, countries like Germany, South Africa, and Argentina offer models of historical reckoning through truth councils, reparative justice, and institutional memory work (Rothberg, 2009).

Bangladesh can learn from these experiences by:

-Establishing institutional independence for memory bodies.

-Linking memory work with human rights advocacy.

-Forming transnational networks for digital memory protection.

-Promoting collective commemoration that transcends partisanship.

International support—especially from UNESCO, ICOMOS, and digital humanities organisations—can play a pivotal role in protecting endangered heritage and amplifying silenced histories.

8.7 Risks and Opportunities Ahead

The future of memory politics in Bangladesh hangs in a delicate balance. The authoritarian backsliding, intensified surveillance, and post-truth politics threaten the preservation of authentic history. On the other hand, technological innovation, youth activism, and global solidarity offer unprecedented tools for democratizing memory.

The risk lies in fragmentation, where conflicting narratives, deepening polarization, and historical illiteracy fracture the national fabric. The opportunity lies in regeneration, where memory becomes not a source of division but a foundation for moral unity and democratic continuity.

8.8 Memory as Democratic Infrastructure

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman once declared, ‘The struggle this time is the struggle for our emancipation.’ That struggle continues—not only in the realm of politics or economics but in the domain of memory. To erase Mujib is to erase the story of emancipation, and to preserve him is to reclaim the possibility of freedom rooted in justice, dignity, and truth.

The politics of memory must evolve into a memory of politics—a vigilant awareness of how power manipulates history and how people resist such manipulation through mourning, documentation, education, and protest.

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. The future of its democracy depends in part on the future of its memory—on whether it chooses authoritarian amnesia or democratic remembrance. This study calls for an urgent collective commitment to the latter.

9: Conclusion

9.1 Memory as a Democratic Battleground

In Bangladesh, the project of remembering is profoundly political. The memory of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—his assassination, his ideology, his role in the Liberation War, and his contested legacy—remains central to the nation’s identity. From 1975 to 2024, we have witnessed the construction, distortion, suppression, and revival of that memory in a turbulent dance with state power, populist politics, and algorithmic manipulation. What began with silencing a leader has evolved into a deeper contest over who gets to remember, what is remembered, and how that memory shapes collective futures.

This conclusion offers reflective insights into what the history of these assaults tells us about Bangladesh’s trajectory and how memory can be reimagined as resistance, reconciliation, and nation-building. It also proposes a vision for a more inclusive, accountable, and democratically embedded memory infrastructure in Bangladesh.

9.2 The Politics of Forgetting: Authoritarianism and Memory Regimes

Memory politics in Bangladesh has often served as a tool for authoritarian consolidation. Whether under the military regimes of Ziaur Rahman and Ershad or in more recent pseudo-democratic governments, state actors have consistently tried to reshape or suppress historical memory to consolidate legitimacy.

These efforts were often justified in the name of stability, neutrality, or modernization, but in practice, they sought to:

-Relativize Sheikh Mujib’s central role in Bangladesh’s liberation.

-Erase evidence of military culpability in the 1975 massacre.

-Promote counter-histories that recast political rivals as national heroes.

-Censor the cultural and academic production of Mujib-centric false narratives.

-Digitally suppress or algorithmically manipulate memory in social media and digital repositories.

The 2024 assault on the Dhanmondi 32 Museum, a site etched into the emotional and national consciousness of Bangladesh, was not an anomaly. It was the meticulously well-designed erasing of national memories and vandalism by radical militants.

9.3 The Resilience of Memory and the Power of Counter-Narratives

Despite the systemic erasures, memory has endured—not as a monolith, but as a pluralistic and living force. Memory, in this sense, became resistance. Grassroots movements, the diaspora, independent historians, artists, and digital archivists have all played key roles in resurrecting suppressed truths.

We saw examples of this resilience in:

-Oral history movements that preserved war memories across generations.

-The rise of diasporic memory archives, especially in the UK, USA, and Canada.

-Student-led remembrance initiatives (e.g., #Remember1975 and #JusticeforMujib).

-The digital restoration of banned books, videos, and public speeches.

-Artistic productions that refused to obey the state’s historical silences.

As Rothberg (2009) and Nora (1989) have argued, memory exists in a tension between institutional monuments and living communities, between militant-supported state narratives and public resistance. Bangladesh is now in a moment where those counter-narratives are no longer just acts of cultural dissent—they are emerging as foundations for new democratic imaginaries.

9.4 What the 2024 Assault Revealed About Memory in Crisis

The events of 2024 were an event of erasing freedom fight of 1971, Language Movement of 1952, Six points of 1966, mass uprising of 1969.

-The symbolic space of mourning was converted into a battlefield of radical militants, who supported state suppression.

9.5 Toward Memory Justice: A Democratic Future

What might memory justice look like for Bangladesh? Based on the analysis across this article, five interlinked dimensions are essential:

1. Legal Recognition and Protection

Laws must protect memory spaces, punish historical distortion, and guarantee archival access. A National Memory Protection Act (as proposed in Section 8) is essential to prevent future assaults on places like Dhanmondi 32 and ensure that no regime can rewrite history with impunity.

2. Institutional Independence

Institutions such as the Liberation War Museum, National Archives, and education boards must be insulated from political interference. Memory commissions modeled on global truth-telling institutions should be introduced (Tutu, 1999; Rothberg, 2009).

3. Educational Pluralism

Memory education should move beyond rote curriculum into participatory, inclusive, and critically engaged forms. Students must not only learn facts but also feel the moral weight of historical events like the 1971 war and the 1975 coup.

4. Digital and Algorithmic Safeguards

Bangladesh must treat digital memory as a public good. Partnerships with global digital rights organizations are necessary to combat disinformation, preserve data integrity, and protect public memory infrastructure online (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

5. Cultural and Civic Participation

Art, literature, theatre, and public storytelling must be encouraged to democratize memory. Memory cannot be preserved by archives alone; it must live through people—in festivals, murals, oral traditions, and intergenerational rituals.

9.6 Global Comparisons and Strategic Lessons

Memory politics in Bangladesh is not unique. The Turkish state’s repression of Kurdish history, Argentina’s Dirty War cover-ups, Russia’s rewriting of Soviet-era purges, and India’s erasure of anti-colonial Muslim heroes all reveal how authoritarian regimes manipulate memory (Olick & Robbins, 1998).

What Bangladesh can learn:

From Germany: rigorous truth-telling, institutional humility, and the legal criminalization of Holocaust denial.

From South Africa: healing through testimony, as seen in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

From Rwanda: post-genocide memory laws that criminalize incitement and distortion.

9.7 Conclusion and Final Reflections

Memory as Hope and Resistance, Memory justice is not just about the past—it is a moral infrastructure for the future. In the face of repeated attacks, memory remains a form of hope. The memory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—his speeches, ideals, and martyrdom—has outlived military juntas, textbook revisions, social media blackouts, and political betrayals. That endurance is a testament to the people’s moral intuition, their refusal to forget what matters. Memory is not a luxury of the past—it is a necessity for the future. Bangladesh cannot build democratic continuity, civic empathy, or pluralistic nationalism without safeguarding the story of its birth and the memory of its founding leader. The 2024 assault on Dhanmondi 32 has laid bare the vulnerability of symbolic spaces in authoritarian contexts.

The policy proposals outlined above—from legal frameworks and educational mandates to digital archives and civic partnerships—form a blueprint for memory justice. These frameworks must be future-proofed, inclusive, and resistant to regime change. Only then can Bangladesh move from a reactive to a proactive memory system, where remembrance is not only about preservation but also about empowerment, reflection, and democratic renewal.

Bangladesh cannot afford a land of total blank—not now, not after 1971, and not after 2024. The future must be built on memory that is ethical, inclusive, transgenerational, and just. Only then can Bangabandhu’s dream of a ‘Sonar Bangla’ truly find its full realization.

References

Ahmed, S. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2004). The Politics of Secularism in Bangladesh. Routledge.

Akçam, T. (2012). The Young Turks’ Crime Against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press.

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge University Press.

Bangladesh Ministry of Information. (2024). Public statements on Dhanmondi 32 redevelopment. [Press releases].

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. University of Oxford.

Butler, J. (2004). Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. Verso.

Chakrabarty, D. (2015). The Crises of Civilization: Exploring Bangabandhu’s Worldview. South Asia Journal.

Chowdhury, N. (2021). Digital Memory and the Construction of Political Legacy: The Case of Sheikh Mujib. Bangladesh Journal of Media Studies, 3(1), 55–78.

Connerton, P. (1989). How Societies Remember. Cambridge University Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon.

Green, P. (2019). The Rohingya Crisis and Genocide Denial. Journal of Genocide Studies, 11(2), 120-140.

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On Collective Memory (L. Coser, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press.

Human Rights Watch. (2024). Bangladesh: Assault on Dhanmondi 32 Museum and Memory. Human Rights Watch Report.

Kabir, H. (2013). Language, Identity and Politics in South Asia. University of Dhaka.

Kamal, M. A. (2005). 1971: Documents and Speeches. University Press Limited.

Mbembe, A. (2003). Necropolitics. Public Culture, 15(1), 11–40.

Nora, P. (1989). Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations, (26), 7–24.

Olick, J. K., & Robbins, J. (1998). Social Memory Studies: From ‘Collective Memory’ to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practices. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 105–140.

Rashid, M. (2012). Diplomacy of Mujib: Bangladesh at the UN. South Asian Diplomatic Review, 2(4), 12–28.

Rosa, H., & Muro, M. (2021). Algorithmic Governance and Digital Censorship. Journal of Digital Politics, 12(2), 45–69.

Rothberg, M. (2009). Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford University Press.

Said, E. W. (1994). Culture and Imperialism. Vintage Books.

Saussure, F. de. (1983). Course in General Linguistics (R. Harris, Trans.). Duckworth. (Original work published 1916)

Sobhan, R. (2000). Rediscovering the Bangladesh Economy: Political Economy of Development. Centre for Policy Dialogue.

Spencer, J. (2008). Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict. Routledge.

The Daily Star. (2024). Reports on Dhanmondi 32 site restrictions and demolitions. [Online news portal].

Tumarkin, N. (1997). Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia. Harvard University Press.

Tutu, D. (1999). No Future Without Forgiveness. Doubleday.

UNESCO. (2017). Memory of the World: 7 March Speech of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.