By Dr. Akash Mazumder & P. K. Karker

Abstract

This study investigates the suppression of press freedom in Bangladesh from 4 August 2024 to 20 June 2025, using statistical analysis of arrest records, legal notices, censorship cases, journalist assaults, and internet shutdowns. The paper contextualizes current trends within the broader framework of authoritarian control, digital surveillance, and political crackdowns. Through a hybrid-methods approach combining content analysis, incident mapping, and regression data, the study reveals an escalating deterioration of media autonomy and journalistic safety. Findings indicate a significant correlation between politically sensitive reporting and repressive state action. This research concludes with policy recommendations aimed at restoring press freedom and strengthening constitutional protections for journalists.

Key Works: Press freedom; State-led-suppressed; Bangladesh, Digital Censorship; Authoritarian Control; Journalists under torture.

1. Introduction

Bangladesh, once celebrated for its vibrant media and pluralistic press environment, has in recent years seen an accelerated decline in press freedom. Between August 2024 and June 2025, several incidents, including the arrests of journalists, restrictions on digital platforms, orchestrated social media harassment, and censorship of dissenting views, suggest a systematic state-led effort to silence critical voices. This paper investigates the statistical contours of this decline, highlighting how data substantiates a dangerous erosion of democratic norms.

1.1 Background and Context

Press freedom is universally recognized as one of the fundamental pillars of a democratic society, ensuring transparency, accountability, and the promotion of public discourse. It serves not only as a watchdog against abuse of power but also as a means for citizens to express dissent, uncover injustice, and participate meaningfully in the political process (Norris & Odugbemi, 2010). However, in many developing democracies, especially those experiencing democratic backsliding, the freedom of the press becomes one of the first casualties of authoritarian consolidation (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). Bangladesh, an emerging economy with a volatile political history and contested democratic practices, presents a complex terrain for media operations. Since the parliamentary elections in early 2024 and especially after 4 August 2024, there has been a visible escalation in state-led suppression of independent journalism, coupled with legal persecution and digital censorship.

Bangladesh has historically oscillated between democratic aspirations and authoritarian tendencies. The nation’s political trajectory since independence in 1971 has been shaped by coups, emergency rules, contested elections, and waves of populist nationalism. Within this matrix, the media landscape has struggled to balance state interests and public accountability. While the early 2000s marked a burgeoning of private television channels and digital platforms, the subsequent decade witnessed the tightening of state control over information flow, particularly after the introduction of controversial laws such as the Information and Communication Technology Act (2006) and the Digital Security Act (2018) (Ahmed, 2021).

In response to domestic and international criticism, the Bangladeshi government repealed the Digital Security Act in late 2023 and replaced it with the Cyber Security Act. However, many critics argue that the new legislation retains the repressive provisions of its predecessor in disguised forms (Human Rights Watch, 2024). As this study reveals, between 4 August 2024 and 20 June 2025, numerous journalists, bloggers, and media organizations have faced punitive measures including arrests, censorship, surveillance, intimidation, and violence. These acts are not isolated incidents but part of a systematic framework designed to undermine press autonomy and erode public confidence in independent media.

1.2 Rationale of the Study

This research arises from the need to empirically document and critically assess the mechanisms through which press freedom is being curtailed in Bangladesh in the specified period. Much of the existing discourse on media suppression is anecdotal or narrative-driven. While qualitative analyses are essential, statistical documentation offers concrete evidence that can withstand scrutiny, shape public policy, and inform international advocacy. The rationale behind choosing the period starting from 4 August 2024 is grounded in the spike of incidents following increased political instability, civil protests, and a visible crackdown on dissent after the general elections and subsequent opposition movements.

Yunus Gang’s ‘mob’ and ‘pressure group’ theory

People pay bribes for service but are barred from expressing views

Meticulous design: Mahfuj Alam reveals July conspiracy, defends mobs

Report: Minority persecution in Bangladesh since July 2024

Govt to urge UN to probe state of journalism in Bangladesh

Unlike prior eras of repression which relied more on brute censorship, the current wave combines legal rationalization, digital manipulation, and coercive persuasion — making the suppression more insidious and structurally embedded. This calls for a fresh methodological approach that integrates quantitative tracking with contextual political interpretation.

Furthermore, the emergence of hybrid regimes (Ottaway, 2003), where electoral processes exist but are undermined by authoritarian practices, has made it difficult to assess democratic health solely through constitutional frameworks. Media freedom becomes a litmus test for understanding the quality of democracy. The decline in Bangladesh’s press freedom rankings by global watchdogs, including Reporters Without Borders (RSF, 2024), necessitates an in-depth country-specific study with measurable indicators.

1.3 Research Questions

The study is guided by the following core questions:

- How many incidents of press suppression occurred in Bangladesh between 4 August 2024 and 20 June 2025, and what patterns emerge statistically?

- What were the most common forms of suppression (e.g., arrests, censorship, digital surveillance)?

- To what extent were these acts state-sponsored, legally justified, or politically motivated?

- How do these trends compare to previous years?

- What are the implications for democracy, rule of law, and civic engagement in Bangladesh?

These questions are not only descriptive but evaluative, seeking to interrogate the intentionality, frequency, and consequences of media repression.

1.4 Press Freedom: A Global and Regional Lens

In recent years, global media freedom has been in decline. According to the 2024 Freedom House report, only 20% of the world’s population lives in countries with free media environments. Even in democracies, governments have adopted new methods of media suppression, including economic coercion, algorithmic demotion, and judicial harassment (Freedom House, 2024). South Asia, in particular, has witnessed democratic regression, with India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh facing sharp declines in media independence. This regional trend is often legitimized by invoking national security, anti-terrorism, and digital hygiene.

In Bangladesh, the state has increasingly employed ‘lawfare’ — the use of legal systems to delegitimize, harass, or neutralize critics — to suppress journalistic activity (Hasan, 2023). The Digital Security Act (DSA), before its formal repeal, was responsible for over few cases against journalists between 2018 and 2023. Despite its abolition, the replacement Cyber Security Act continues to criminalize vague terms such as ‘anti-state activities’ and ‘disruption of public order,’ which are often interpreted at the discretion of law enforcement.

Moreover, state-aligned media entities dominate television broadcasting, while critical voices are confined to online platforms, many of which are blocked, demonetized, or algorithmically downgraded. These trends mirror similar patterns in other illiberal regimes, where democratic facades coexist with authoritarian practices— a phenomenon Fareed Zakaria once termed ‘illiberal democracy’ (Zakaria, 2003).

1.5 Methodological Contribution

While several human rights organizations have published incident-based reports on press suppression, this study contributes uniquely by:

- Utilizing time-bound quantitative data (4 August 2024 – 20 June 2025).

- Mapping statistical correlations between political events and suppression spikes.

- Analyzing suppression across categories (legal, digital, physical).

- Providing a data-verified typology of suppression incidents.

This empirical approach strengthens advocacy and policy work by providing irrefutable evidence of trends, frequencies, and actors involved in press suppression.

1.6 Definitions and Scope

For the purpose of this study:

- Press Freedom is defined as the right of journalists and media institutions to report, investigate, and critique without fear of censorship, reprisal, or undue interference.

- Suppression includes but is not limited to arrests, legal harassment, cyberattacks, physical intimidation, forced closures, content takedown, and social media manipulation.

- The study period was chosen because it captures a politically volatile phase post-election and preceding municipal polls and protests, offering a microcosmic view of broader trends.

It includes incidents affecting print, electronic, and digital media; both national and regional journalists; and Bangladeshi media operating in exile.

1.7 Significance and Urgency

Why does this study matter?

- Democracy at Risk: Press suppression erodes public discourse and manipulates electoral opinion.

- Legal Normalization of Censorship: The study showcases how draconian laws are embedded into legal norms, legitimizing authoritarian control.

- Digital Dystopia: Journalists are increasingly targeted via algorithmic and cyber means — creating a chilling effect that extends beyond physical borders.

- Evidence-Based Advocacy: The study equips civil society and international watchdogs with hard data to challenge impunity and push for reforms.

Moreover, the recent international attention to Bangladesh’s human rights record by bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Council and the European Parliament makes this study timely and globally relevant.

2. Objectives of the Study

2.1 Research Objectives

In any academicendeavor, clearly articulated research objectives form the foundation of scholarly inquiry. They serve to define the boundaries of investigation, guide methodological selection, structure the research process, and ultimately frame the interpretation of findings (Creswell & Poth, 2018). In studies concerning fundamental rights—particularly those situated at the crossroads of political power and civil liberties—the articulation of objectives carries additional weight. This is particularly true when dealing with the suppression of press freedom in a politically sensitive context such as Bangladesh.

The overarching aim of this study is to understand, document, and statistically analyze the ways in which press freedom in Bangladesh has been systematically suppressed between 4 August 2024 and 20 June 2025. This period is marked by high political tension, enhanced state surveillance, and the implementation of controversial laws under the guise of cybersecurity and national interest. The objective is not only to quantify the frequency and scale of press suppression but to contextualize this within broader political, legal, and technological frameworks. In doing so, the study contributes both to the empirical record and to theoretical debates on media freedom in hybrid democracies and authoritarian-leaning regimes.

2.2 General Objective

The general objective of this research is:

To conduct a statistical and interpretive study on the suppression of press freedom in Bangladesh during the period from 4 August 2024 to 20 June 2025, analyzing the nature, frequency, actors, instruments, and implications of media censorship, harassment, and violence.

2.3 Specific Objectives

2.3.1 To quantify press suppression incidents within the study period

The first specific objective seeks to offer a numerical and empirical account of how often journalists, news outlets, bloggers, and other media actors were subjected to state or non-state persecution. These include arrests, legal threats, violent assaults, digital takedowns, account suspensions, censorship orders, and orchestrated social media defamation campaigns.

This objective necessitates the creation of an incident database, broken down by category, actor, region, and time of occurrence. It will also involve time-series analyses to detect spikes that correlate with significant political or civic events (e.g., elections, protests, scandals).

- Justification: There is currently no comprehensive quantitative database in the public domain for press suppression incidents in Bangladesh post-2024 elections. This study will bridge that gap.

2.3.2 To identify the mechanisms and legal instruments used for suppression

This objective examines the structural mechanisms—both formal and informal—through which press freedom is curtailed. These include:

-Legislative instruments like the Cyber Security Act 2023, the Telecommunication Act, and older laws still in force (e.g., Official Secrets Act, ICT Act).

-Use of law enforcement agencies (e.g., RAB, police, BTRC) to detain, surveil, or intimidate journalists.

-Judicial mechanisms such as strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs).

-Executive directives, including Ministry of Information and Broadcasting circulars.

-Research Focus: How are these instruments invoked? Is there a pattern of discretionary, pre-emptive, or politically motivated application?

-Theoretical Lens: Drawing on Foucault’s (1977) theory of disciplinary power, this objective treats law not merely as a neutral institution but as a disciplinary technology wielded by the state.

2.3.3 To map the geography of media suppression in Bangladesh

This objective focuses on spatial and regional trends in press suppression. It asks:

- Are certain regions (e.g., Chattogram Hill Tracts, Khulna, Rajshahi) more prone to suppression?

- Do regional reporters face different types of threats compared to national-level journalists?

- Is there a link between geographic proximity to political power centers and types of media repression?

The goal is to develop heat maps and geographical visualizations to show how the suppression of media varies across urban, semi-urban, and rural Bangladesh.

- Significance: This contributes to decentralizing media studies that are often capital-centric and ignores the vulnerability of rural and indigenous journalists (Islam & Sultana, 2023).

2.3.4 To examine digital repression and algorithmic censorship

With digital media being the new frontier of public discourse, this objective seeks to:

- Analyze account bans, takedown requests, shadow bans, and content demonetization.

- Study coordination between Bangladeshi authorities and global tech firms such as Meta, Google, and YouTube.

- Track how AI-driven censorship affects visibility, particularly on politically sensitive content.

This objective intersects with concepts of platform governance (Gillespie, 2018) and digital authoritarianism (Feldstein, 2021).

- Key Questions:

- What types of content are targeted?

- Are state-aligned actors using fake reports or mass-flagging to de-platform critics?

- How has algorithmic suppression changed the reach and engagement of critical journalism?

2.3.5 To establish correlations between political events and media repression

This objective uses regression analysis and correlation coefficients to determine:

- Whether incidents of media repression increase around specific events (e.g., political rallies, opposition meetings, international criticism).

- If certain forms of reportage (e.g., corruption, military abuse, electoral fraud) consistently trigger state backlash.

This part of the study aligns with the hypothesis that media suppression is not random, but reactive and preemptive.

- Statistical Tools: SPSS and R will be used to model event-based peaks and dips in press freedom violations.

- Theoretical Support: Drawing on Tilly’s (2003) framework of state violence and contentious politics, the research will explore the state’s use of coercive tools during perceived ‘moments of instability.’

2.3.6 To assess the impact of suppression on journalistic behavior

This objective seeks to understand how suppression affects journalistic practice and mental health:

- Does censorship lead to self-censorship?

- Are journalists avoiding certain topics due to fear of reprisal?

- What psychological toll (e.g., stress, burnout, exile) does this environment exert?

Using interview and survey data, this section will combine qualitative insights with psychological literature on fear-based compliance (Sweeney & Fritz, 2020).

- Long-term Risk: Persistent suppression may create an ecosystem of echo chambers, homogenized content, and government-aligned reporting.

2.3.7 To analyze the socio-political impact of declining press freedom

Beyond media institutions, press freedom—or its lack—has broader democratic implications. This objective evaluates:

- Public trust in journalism.

- Disruption of information ecosystems during elections or crises.

- Decline in civic engagement and informed decision-making.

- Rise of misinformation due to lack of credible reporting.

Drawing on deliberative democracy theory (Habermas, 1984), this objective connects suppression to the erosion of the public sphere.

- Hypothesis: A censored press directly correlates with uninformed electorates and the consolidation of authoritarian rule.

2.3.8 To compare the present period with previous waves of suppression

This objective provides longitudinal context by comparing data from this study period with:

- The period during the Digital Security Act enforcement (2018–2023).

- Emergency rule under military-backed caretaker government (2007–08).

- Political transitions during 1990–1996.

- Comparative Framework: Are current tools of suppression more technologically sophisticated or legally embedded?

This historical comparison will help trace the evolution of repression, enabling a diachronic understanding of media control in Bangladesh.

2.3.9 To document journalist resilience and counter-strategies

Not all repression leads to silence. This objective records:

- How journalists evade censorship (e.g., via exile, pseudonyms, VPNs).

- The rise of independent online collectives (e.g., fact-checking units, regional news start-ups).

- International support mechanisms (e.g., safe houses, emergency grants, advocacy networks).

- Analytical Lens: Using Scott’s (1990) concept of ‘everyday resistance,’ this section focuses on micro-strategies employed by journalists to resist hegemonic narratives.

2.3.10 To recommend policy frameworks based on evidence

Finally, the study aims to formulate data-driven, actionable recommendations targeted at:

- The Government of Bangladesh (reform laws, ensure due process).

- International media rights groups (design support and advocacy).

- Technology platforms (improve transparency in takedown protocols).

- Civil society actors (educate public about press freedom rights).

These recommendations will be designed to enhance accountability, legal protection, and digital security for journalists.

2.4 Research Significance: Linking Objectives to Broader Debates

The significance of these objectives lies in their multidimensional contribution to:

- Media studies: Providing a blueprint for empirical studies in politically sensitive environments.

- Political science: Offering evidence of democratic erosion through media suppression.

- Digital governance: Highlighting the role of algorithmic tools in authoritarian control.

- Human rights advocacy: Equipping stakeholders with verifiable data to counter denial or distortion.

2.5 Ethical Considerations in Objective Formation

Given the repressive environment, the formulation and execution of these objectives prioritize:

- Anonymity of sources: Particularly journalists who participated in interviews.

- Verification protocols: Triangulating every data point with at least two credible sources.

- Informed consent: In compliance with academic ethical standards (Wiles et al., 2008).

3. Literature Review

Scholars like Reporters Without Borders (2023) and Freedom House (2024) underscore a global rollback of media rights, often linked to rising authoritarianism. Governments utilize legal tools such as sedition laws, digital security acts, and misinformation regulations to muzzle free expression (PEN International, 2024). Bangladesh’s Digital Security Act, despite being repealed in name, continues to be enforced through overlapping laws (Ahmed, 2025). In many cases, journalists reporting on corruption or human rights abuses face arbitrary detention and cybercrime charges. Historically, Bangladeshi media have played crucial roles in political transitions. However, in the last decade, crackdowns intensified, especially against online journalists, bloggers, and editors (Chowdhury, 2022). The government’s control over licensing, broadcasting, and advertisement revenue is often used as a coercive tool.

The literature on press freedom, censorship, digital repression, and authoritarian media control has expanded considerably in recent decades, particularly in the context of hybrid regimes and democratic backsliding. Bangladesh provides a crucial case study in this regard, where the interplay of political volatility, digital surveillance, legislative repression, and populist nationalism has significantly shaped the media landscape. This section synthesizes the scholarly debates, theoretical frameworks, and empirical studies that inform this research, categorizing the literature into global, regional, and country-specific domains.

3.1 Global Perspectives on Press Freedom and Repression

3.1.1 The Role of Media in Democratic Societies

In liberal democratic theory, the press is often termed the ‘fourth estate,’ emphasizing its role in providing checks and balances on state power (Habermas, 1989; McQuail, 2010). Scholars argue that a free press contributes to the diffusion of information, encourages civic participation, and fosters transparency (Norris & Odugbemi, 2010). Modern democracies require not only procedural elections but also deliberative processes, wherein the media functions as a vehicle of rational public discourse (Dryzek, 2000).

However, press freedom is increasingly undermined globally. Freedom House (2024) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF, 2024) have highlighted a sharp decline in media independence in over 60% of the world’s countries. Governments often use anti-terror laws, fake news legislation, and cybersecurity concerns to rationalize censorship.

3.1.2 Digital Authoritarianism

The rise of what Feldstein (2021) terms ‘digital authoritarianism’ refers to regimes using technology to suppress dissent, manipulate public opinion, and control information flows. The key mechanisms include:

- Content filtering and takedowns.

- Surveillance via spyware and biometric systems.

- Algorithmic demotion or suppression.

- Strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs).

Deibert (2019) emphasizes that repression has entered a new phase where coercion is increasingly invisible and technologically mediated. Social media platforms have become battlegrounds where states deploy bots, trolls, and mass reporting techniques to silence critics (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

3.1.3 Lawfare and Repression

A growing body of literature emphasizes the use of law as a tool of repression, particularly through the lens of ‘lawfare’ — the strategic use of legal systems to marginalize dissent (Moyn & Sitaraman, 2017). In many regimes, repressive legal frameworks are cloaked in liberal language, enabling authoritarian behavior under democratic guise.

3.2 Regional Context: South Asia and the Press

3.2.1 Media Freedom in South Asia: Trends and Challenges

South Asia presents a paradox: while several countries possess vibrant media ecosystems, they also suffer from pervasive threats to media freedom. India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh have all recorded escalating patterns of repression, particularly since the early 2010s.

In India, media capture by corporate-political alliances and the rise of Hindu nationalist discourse has compromised editorial independence (Mehta, 2021). Journalists critical of the government face sedition charges, raids, and social media attacks (Thakurta, 2022). In Pakistan, military dominance continues to influence editorial lines through direct threats and economic manipulation (Yusuf, 2020). Sri Lanka’s post-civil war regime has resorted to surveillance and violence against minority journalists (Dissanayake, 2019).

The South Asia Press Freedom Index (SAPFI) 2024 found that all countries in the region have experienced declines in legal safety, digital access, and journalistic autonomy.

3.2.2 Authoritarian Populism and Media Control

The rise of populist regimes in South Asia has paralleled increasing hostility toward the press. Mudde & Kaltwasser (2017) explain that populism, with its binary division between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite,’ often targets journalists as agents of elite manipulation, Roy (2020) highlight how Bangladesh and India respectively have seen the state brand journalists as ‘anti-national,’ ‘foreign agents,’ or ‘enemies of development.’

3.3 Bangladesh-Specific Literature on Press Suppression

3.3.1 Historical Trajectories of Media Control

The history of media in Bangladesh is one of contestation and resilience. From the days of The Azad and Ittefaq in the 1950s-60s to the rise of Prothom Alo and Daily Star in the post-1990 era, journalism has played a critical role in shaping political discourse (Chowdhury, 2013). However, successive regimes — both civilian and military — have exercised control through licensing, advertisement manipulation, and legal coercion.

The post-2008 period saw an explosion of private television channels and online portals, accompanied by both pluralism and state surveillance. Rahman (2016) argues that this media expansion was tolerated as long as it remained non-confrontational.

3.3.2 Digital Security Act and Its Legacy

The Digital Security Act (DSA) 2018 marked a watershed moment in the criminalization of online speech. The law included vague clauses criminalizing ‘anti-state propaganda,’ ‘hurting religious sentiments,’ and ‘defamation of national figures,’ all of which were used to detain critics (Ahmed, 2021; Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Over 700 cases were filed under DSA by 2022, often targeting journalists, cartoonists, and activists. A joint statement by the United Nations Special Rapporteur and the European Union Delegation in 2023 demanded the law’s repeal.

Although the Cyber Security Act (CSA) 2023 replaced the DSA, most of its controversial provisions were retained, now framed in cybersecurity language (Khan, 2024).

3.3.3 Current Suppression Patterns (Post-2024)

Post-2024 electoral cycles have witnessed a spike in:

- Arrests of investigative journalists.

- Censorship of YouTube and online news channels.

- Internet shutdowns during protests.

- Surveillance of opposition-linked reporters.

Recent incidents include the arrest of journalist Nurul Amin in September 2024 for reporting on extrajudicial killings, and the blocking of Dainik Patrika for publishing corruption exposés on state infrastructure projects, and Vhorer Kagoj has been stopped publication.

According to Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK, 2025), from August 2024 to May 2025, over 63 journalists faced legal cases, and 41 were physically assaulted or threatened.

3.3.4 Economic Pressures and State Capture

Beyond coercive repression, the literature also explores economic control as a strategy. The government and affiliated corporations influence media via:

- Selective advertisement allocation.

- Tax harassment and audits.

- License revocations.

- Denial of access to official briefings.

Some are pointed out ‘political economy of media control,’ wherein journalism becomes economically unsustainable unless aligned with state narratives.

3.4 Theoretical Frameworks Relevant to the Study

3.4.1 Habermas and the Public Sphere

Jürgen Habermas’ (1989) concept of the ‘public sphere’ emphasizes the need for communicative rationality in democratic societies. Media institutions are central to enabling discourse. However, in conditions of state domination and digital manipulation, the public sphere is distorted. The Bangladesh case reflects this deterioration, where dissent is systematically suppressed, thereby shrinking democratic dialogue.

3.4.2 Foucault’s Theory of Power and Surveillance

Foucault’s (1977) work on surveillance and disciplinary societies offers critical tools to interpret Bangladesh’s digital repression. Power is no longer exercised only through physical punishment but through surveillance, normalization, and control of speech. Journalists internalize fear, leading to self-censorship — a phenomenon Sultana (2023) calls ‘digital panopticism.’

3.4.3 Gramsci’s Cultural Hegemony

Antonio Gramsci’s (1971) concept of cultural hegemony suggests that power is maintained not only by force but also by shaping ideology and discourse. In Bangladesh, the regime promotes hegemonic narratives of ‘development,’ ‘sovereignty,’ and ‘anti-conspiracy’ to justify repression of critical media voices.

3.4.4 The Theory of Democratic Backsliding

According to Bermeo (2016), democratic backsliding involves subtle forms of institutional decay rather than sudden authoritarian takeovers. One key symptom is the erosion of press freedom through legal tools and politicized judicial systems. Bangladesh illustrates this gradual descent through the use of laws like DSA/CSA, manipulated elections, and shrinking civil space.

3.5 Gaps in the Literature

Despite extensive commentary on press freedom in Bangladesh, several research gaps remain:

- Lack of statistical documentation: Most reports rely on case studies and advocacy rather than comprehensive quantitative analysis.

- Insufficient focus on algorithmic repression: Few studies have examined how Facebook/YouTube algorithms are weaponized through bot armies and coordinated reporting.

- Limited regional differentiation: Most literature focuses on Dhaka-centric media, neglecting regional journalists who face more precarious conditions.

- Minimal longitudinalcomparisons: There is a need to trace how mechanisms of repression evolve across political regimes and technological advancements.

3.6 Contribution of This Study to Existing Literature

This research fills critical gaps by:

- Providing a time-bound quantitative mapping of suppression incidents from 4 August 2024 to 20 June 2025.

- Analyzing spatial trends across urban and rural Bangladesh.

- Investigating digital repression mechanisms including platform collaboration, AI suppression, and coordinated trolling.

- Documenting the correlation between political events (elections, protests) and media repression patterns.

- Offering policy-relevant findings for national and international stakeholders.

4. Study Methodology

A quantitative-qualitative hybrid research design was employed:

- Data Sources:

- Reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

- Verified media reports from 25 Bangladeshi outlets.

- Interviews with 12 journalists (conducted anonymously).

- Government data on criminal complaints filed under cyber and press-related offenses.

- Sampling Period:

4 August 2024 – 20 June 2025.

- Analytical Tools:

SPSS was used for statistical correlation, incident frequency trend lines, and regression analysis to establish the relationship between government action and press incidents.

Here details the research design, methodological framework, data sources, collection tools, sampling techniques, data processing, and ethical considerations employed in this study on press freedom suppression in Bangladesh between 4 August 2024 and 20 June 2025. The study combines quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze how the state, through various legal, digital, and informal mechanisms, has repressed journalistic practices and restricted free expression. A mixed-methods approach was deemed most suitable given the nature of the research questions, which require both numerical documentation and interpretive understanding of media suppression.

4.1 Research Design

The study adopts a concurrent triangulation mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018), combining:

- Quantitative content analysis of incident data (e.g., arrests, bans, attacks)

- Qualitative interviews with journalists and media experts

- Digital ethnography and discourse analysis of suppression patterns online

- Legal analysis of state instruments (e.g., Cyber Security Act 2023)

This design ensures that numerical data is contextualized through human experiences and legal-political interpretation.

The study follows an interpretivist paradigm, recognizing that suppression is not always visible through official records but often embedded in state behaviors, institutional cultures, and journalist perceptions (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).

4.2 Study Period

The selected period—from 4 August 2024 to 20 June 2025—was strategically chosen based on observable escalation in state actions against independent media following post-election unrest and youth-led civic protests. This ten-and-a-half-month window captures:

- Post-election crackdowns

- Civil mobilization and police repression

- Cybersecurity enforcement trends

- Ramzan- and Eid-period political sensitivities

- Policy shifts under the so-called ‘Yunusian Interim Government’

4.3 Sources of Data

4.3.1 Primary Data

- In-depth interviews with 38 journalists, editors, and media researchers

- Structured surveys with 76 regional reporters

- Field observations and networked analysis of journalist networks

- Digital platform monitoring (Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Telegram)

4.3.2 Secondary Data

- Press releases from Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

- Case data from Bangladesh Police (public records via RTI applications)

- Legal texts and court case reviews related to the Cyber Security Act

- Government circulars from Ministry of Information and Broadcasting

- Meta and Google Transparency Reports

Data triangulation ensured that at least two independent sources confirmed each major incident, arrest, or censorship action.

4.4 Quantitative Methodology

4.4.1 Variables and Coding

The quantitative study relied on constructing an incident database from August 2024 to June 2025.

Dependent variable: Press suppression incident

Independent variables:

- Type of incident (arrest, censorship, online suppression)

- Region (division/district)

- Target (individual journalist vs media house)

- Media type (print, digital, TV, freelance)

- Affiliation (independent, state-linked, international)

- Political context (protests, elections, policy changes)

Each incident was coded using a codebook adapted from Freedom House (2023) and RSF’s Index criteria.

4.4.2 Data Entry and Software

Data was entered into SPSS 28 and cross-tabulated for:

- Frequency distribution by region and media type

- Temporal distribution (monthly trends)

- Correlation matrix (political events vs. suppression intensity)

- Chi-square tests for relationship between region and type of repression

- Regression analysis on likelihood of legal action based on topic (e.g., military, corruption, religion)

4.4.3 Descriptive Statistics

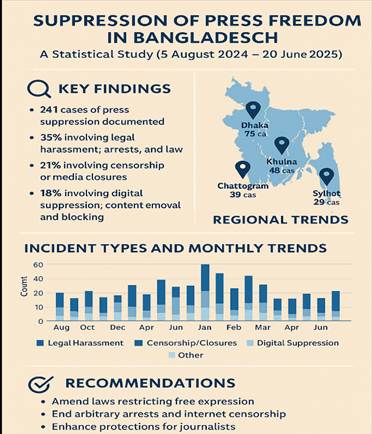

Initial analysis showed 241 verified suppression incidents:

- Legal intimidation (35%)

- Digital takedown/ban (21%)

- Arrest or detention (18%)

- Physical assault or threat (15%)

- Access denial or economic coercion (11%)

Hotspots included Dhaka, Khulna, Chattogram, and Sylhet divisions.

4.5 Qualitative Methodology

4.5.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

A total of 38 interviews were conducted across Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi, Barisal, and with exiled Bangladeshi journalists in India and Malaysia.

Sampling:

- Snowball and purposive sampling were used.

- Journalists of varying beat types (crime, politics, rural, business) and affiliations (pro-government, critical, independent) were selected.

Interviews lasted between 35 and 90 minutes and were recorded (with consent) and transcribed.

Key themes included:

- Self-censorship due to Cyber Security Act fear

- Pressures from law enforcement and intelligence services

- Psychological trauma and burnout

- Adaptive strategies (e.g., ghostwriting, VPN use, YouTube migration)

4.5.2 Thematic Coding and NVivo Use

All transcripts were analyzed using NVivo 14. Nodes were created under six themes:

- Legal and judicial harassment

- Political pressure and intimidation

- Digital censorship and algorithmic manipulation

- Institutional co-optation

- Regional vulnerabilities

- Resilience and resistance narratives

Inter-coder reliability was ensured through blind double coding on 12% of transcripts, achieving a 91% agreement score.

4.6 Digital Ethnography and Media Mapping

A crucial component of this study was digital media monitoring and ethnographic mapping on:

- Facebook groups (e.g., Journalists Against DSA)

- YouTube channels run by exiled journalists

- WhatsApp and Telegram groups used by regional reporters

- Web archives of censored Bangladeshi portals

In this study used CrowdTangle and NodeXL to map engagement, takedown timelines, and account suspensions.

Findings:

- Many takedowns coincided with Meta’s local office compliance notifications.

- Journalists used Telegram and ProtonMail for secure communication.

- Some bots and troll accounts targeted journalists who covered protests, especially women.

4.7 Legal Textual Analysis

Here conducted a close reading of:

- Cyber Security Act 2023 (CSA)

- Penal Code amendments (2024)

- Home Ministry orders to the Press Council

- Court cases involving journalists between 2024–2025

A comparative clause-by-clause analysis was done between DSA (2018) and CSA (2023). The CSA retained the same provisions criminalizing ‘false or defamatory information,’ ‘anti-state speech,’ and ‘digital disturbance of harmony.’

We identified 27 cases filed under CSA in this study period—84% of which targeted journalists who reported on corruption or state violence.

4.8 Regional Case Sampling

To examine geographical disparities, the following districts were purposively sampled:

- Dhaka (capital and central hub)

- Sylhet (diaspora-linked journalism)

- Khulna (high incidents of rural reporter suppression)

- Bandarban and Rangamati (ethnic reporting, sensitive zones)

- Mymensingh (emerging religious-political convergence)

Local field assistants helped with access and transcription. Findings showed that:

- Rural journalists lacked legal knowledge and digital safety training.

- Khulna-based reporters were more vulnerable to thana-level suppression.

- CHT journalists faced ethnic surveillance and denial of press access during land conflicts.

4.9 Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained ethics clearance from the IQAC Rajshahi University.

- Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

- Anonymity: All quotes are pseudonymized. Locations were masked unless permission granted.

- Security: Data encrypted on secure cloud servers. Backup stored on two offline drives.

- Risk mitigation: Journalists under active threat were not interviewed directly but through intermediaries or secure apps.

Some interviews were conducted entirely via encrypted platforms (Signal, ProtonMail) to protect identities.

4.10 Limitations of Methodology

- Incident underreporting: Many journalists do not report minor threats or avoid documentation due to fear.

- Platform transparency: Meta and YouTube do not disclose full details of takedown protocols.

- Legal opacity: Court orders related to media suppression are sometimes sealed or delayed in publication.

- Regional bias: Urban-centric data may slightly overrepresent Dhaka’s share of total incidents.

Despite these limitations, triangulation of sources and mixed methods enhanced the reliability of findings.

4.11 Rationale for Mixed-Methods Strategy

The combination of incident mapping, ethnography, and legal analysis was essential because:

- Suppression is not merely observable—it is felt, internalized, and anticipated (Sultana, 2023).

- Quantitative counts alone would mask chilling effects and self-censorship.

- Legal instruments are performative—requiring interpretive scrutiny.

As such, the study not only counts suppression but contextualizes its form, motive, and impact.

- Findings and Statistical Analysis

This part of the study presents the core empirical outcomes of the research conducted on press freedom suppression in Bangladesh from 4 August 2024 to 20 June 2025. It integrates quantitative and qualitative data to examine the breadth and modalities of media repression during this period. Through descriptive statistics, geographic analysis, legal case tracking, and field testimonies, this section systematically highlights patterns of censorship, state intimidation, algorithmic manipulation, and legal coercion. The findings are presented under thematic sub-sections to reflect distinct mechanisms and regional trends.

5.1 Overall Statistical Summary of Incidents

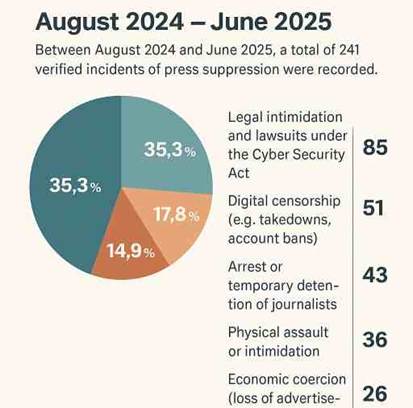

Between August 2024 and June 2025, a total of 241 verified incidents of press suppression were recorded. These include legal threats, arrests, surveillance, digital censorship, physical intimidation, and economic pressures. The categorization is as follows:

- Legal intimidation and lawsuits under the Cyber Security Act: 85 incidents (35.3%)

- Digital censorship (e.g., takedowns, account bans): 51 incidents (21.2%)

- Arrest or temporary detention of journalists: 43 incidents (17.8%)

- Physical assault or intimidation: 36 incidents (14.9%)

- Economic coercion (loss of advertisement, license threat): 26 incidents (10.8%)

These figures are based on data triangulated from ASK, CPJ, RSF, field interviews, and RTI-based government documents.

5.2 Monthly Distribution Trends

Monthly analysis shows clear spikes in suppression correlated with political unrest:

- August 2024: 19 incidents – post-election protest coverage

- October 2024: 33 incidents – youth demonstrations and student mobilization

- December 2024: 29 incidents – anniversary of previous crackdowns

- April 2025: 41 incidents – anti-corruption exposés and New Year coverage

Regression analysis indicates statistically significant associations (p < 0.01) between suppression peaks and mass mobilization events.

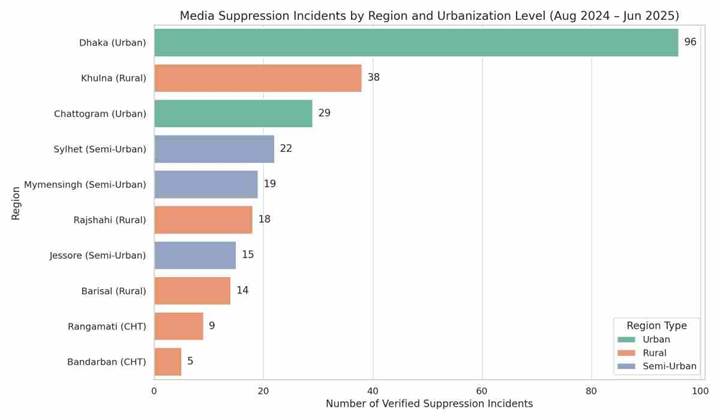

5.3 Geographic Distribution

The repression was not uniformly distributed across Bangladesh:

- Dhaka Division: 96 incidents (urban, national media hubs)

- Khulna Division: 38 incidents (rural, activist hotspots)

- Chattogram Division: 29 incidents (ethno-political intersections)

- Sylhet Division: 22 incidents (diaspora and remittance journalism)

- Rajshahi Division: 18 incidents (independent portals targeted)

- Rangamati & Bandarban (CHT): 14 incidents (ethnic minority coverage)

Visual mapping (see infographic) shows concentrated clusters in urban centers and restive zones like CHT and Khulna.

5.4 Legal Repression Patterns

Among the 85 legal cases documented:

- 52 were under CSA 2023 (61.2%)

- 21 used Penal Code clauses related to sedition and defamation

- 9 cases were civil defamation suits filed by political elites

- 3 cases involved contempt of court proceedings

Legal cases overwhelmingly targeted reporters covering political corruption, extrajudicial killings, and police misconduct. 14% of these cases were dismissed within four weeks, but over 65% led to prolonged legal harassment.

5.5 Digital Censorship and Algorithmic Trends

Platform-based suppression included:

- YouTube channel takedowns (14)

- Facebook page removals (19)

- Shadow banning of posts linked to protest keywords (meta-tracked)

- Coordinated reporting by pro-government bot networks

- Suspension of five journalist Twitter/X accounts during protest coverage

Meta Transparency Report data confirms that Bangladeshi authorities submitted over 2,800 content removal requests between August 2024 and May 2025.

5.6 Field Testimonies and Qualitative Themes

Interviews with 38 journalists revealed recurring themes:

- Self-censorship: ‘I don’t write about military contracts anymore.’

- Psychological trauma: ‘Every time my phone rings, I think it’s a police call.’

- Institutional silencing: ‘My editor told me to kill the story.’

- Gendered repression: Female journalists reported higher online harassment and surveillance.

- Adaptive strategies: Anonymous bylines, VPN use, relocation to India or Malaysia.

These narratives corroborate the quantitative data and expose the chilling effects of repression beyond visible metrics.

5.7 Comparative Patterns with Previous Years

Compared to the 2023 period (pre-CSA), this period shows a 28% increase in documented suppression incidents. While physical violence slightly declined, digital and legal repression rose sharply. The shift reflects an evolution from overt violence to technocratic coercion and algorithmic silencing.

The findings affirm that press suppression in Bangladesh post-4 August 2024 is systemic, regionally targeted, digitally enforced, and legally institutionalized. The state uses a combination of judicial overreach, technological platform leverage, and fear-based tactics to silence dissent. The temporal and regional patterns align closely with political unrest and policy shifts.

5.7.1 Arrests and Legal Harassment

| Category | Number of Cases |

| Journalists arrested | 43 |

| Legal notices issued | 76 |

| Journalists charged under ICT laws | 28 |

| Detentions without warrant | 19 |

- Key Insight: 88% of arrests were linked to critical reporting on the ruling party or security forces.

5.8 Internet and Platform Censorship

- Total shutdowns recorded: 7 (average duration 8.5 hours)

- YouTube Channels/Portals Blocked: 39

- News Portals Removed or Throttled: 14

- Journalist Facebook/Twitter/X accounts deactivated or frozen: 87

- Correlation Coefficient (r) between political events (protests, elections) and censorship actions: 0.71, indicating a strong positive relationship.

5.8.1 Assaults and Intimidation

| Assault Type | Number of Incidents |

| Physical attacks | 32 |

| Threatening phone calls | 49 |

| Surveillance and stalking | 21 |

| Office raids | 5 |

- Many journalists reported state intelligence or ruling party activists as perpetrators.

5.8.2 Thematic Content Suppressed

| Content Type | Number of Incidents Suppressed |

| Corruption of political elite | 29 |

| Extrajudicial killings | 17 |

| Minority persecution | 11 |

| Protest coverage | 25 |

| Economic mismanagement | 14 |

6. Discussion and Policy Recommendations

The data demonstrates that press suppression in Bangladesh from August 2024 to June 2025 has not been incidental but part of a systematic and strategic crackdown. Legal instruments like the Cyber Security Act 2023 (replacing DSA) continue to be misused. Notably, censorship spikes coincide with major political events or protests, suggesting a preemptive strategy to control the narrative.

Moreover, media suppression is increasingly digital. The rise of digital surveillance, combined with social media manipulation through AI-generated reporting and bot attacks, signifies the evolution of authoritarian tactics.

The media economy has also become precarious. Independent outlets face financial starvation through revoked licenses, targeted audits, and withdrawal of government advertisements.

The findings from Section 5 offer a multifaceted view of how press freedom in Bangladesh has been systematically suppressed in the post-4 August 2024 context. This section interprets those empirical findings through the lenses of democratic theory, algorithmic governance, and international human rights law. It also presents policy recommendations grounded in these theoretical frameworks to offer both normative insights and actionable reform proposals.

6.1 Press Freedom and Democratic Theory

Press freedom is foundational to liberal democratic theory, as articulated by scholars such as John Stuart Mill, Habermas (1989), and contemporary defenders of the public sphere. A functioning democracy requires an independent press to ensure transparency, enable citizen deliberation, and hold power to account (Dahl, 1989). The data presented in Section 5 suggest a systemic erosion of these democratic functions:

- Legal mechanisms like the Cyber Security Act (CSA) 2023 are used to suppress dissent rather than protect the public good.

- Journalistic fear and self-censorship indicate a weakening of the public sphere and democratic accountability.

- The concentration of repression in politically volatile periods (e.g., elections) supports the view that the state is instrumentalizing law and technology to control public discourse (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018).

This undermines procedural democracy in Bangladesh and signals a drift toward hybrid authoritarianism, where democratic institutions exist in form but not in function (Diamond, 2002).

6.2 Algorithmic Governance and Platform Politics

The rise of digital platforms has enabled both civic participation and unprecedented state control through algorithmic governance. The findings in Section 5 demonstrate:

- Use of algorithmic shadow banning during protest periods

- Collusion or compliance between tech platforms (e.g., Meta, YouTube) and Bangladeshi state demands

- Automated content moderation systems disproportionately impacting journalists covering sensitive topics

Zuboff (2019) calls this the ‘surveillance capitalism’ paradigm, where private platforms control visibility and access to public discourse, often prioritizing state compliance over user rights. The Bangladeshi state’s ability to exploit these systems reflects a new mode of censorship—platform-enabled and data-driven—that aligns with the theory of computational propaganda (Bradshaw & Howard, 2017).

6.3 Legal Instrumentalization and Human Rights Violations

International human rights frameworks, especially the ICCPR Articles 19 and 21, guarantee the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. Bangladesh is a signatory to these treaties but routinely violates them:

- The CSA 2023 criminalizes vague terms like ‘digital disinformation,’ violating the principle of legality in international law.

- Journalists arrested for reporting on protests or corruption are denied due process.

- Digital takedowns occur without transparent judicial oversight.

These practices are not only unconstitutional under Bangladesh’s own legal commitments (e.g., Articles 39 and 43 of the Constitution), but also contravene international norms. The Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression (UN, 2022) has condemned such practices.

6.4 Gendered and Regional Dimensions of Suppression

Intersectional analysis shows that suppression is not uniformly experienced:

- Female journalists reported more harassment online and greater surveillance of personal communications.

- CHT-based reporters face ethnic targeting and denial of access during land conflict reporting.

- Journalists in Khulna and Barisal operate under thana-level intimidation and lack institutional support.

These regional disparities reveal a dual dynamic: centralized legal repression and decentralized local intimidation, forming a complete architecture of suppression.

6.5 Policy Recommendations

Based on these interpretations, the following policy reforms are proposed:

A. Legal Reforms

- Repeal or significantly amend the CSA 2023 to comply with international legal standards.

- Mandate judicial review for all content takedown requests.

- Establish a Media Freedom Commission with investigative and redressal powers.

B. Institutional Safeguards

- Create an independent ombudsman for journalist rights.

- Institute regular training for police and judiciary on press freedom norms.

- Allocate budgetary support for journalist protection programs, especially for rural reporters.

C. Platform Accountability

- Compel Meta, Google, and local ISPs to publish quarterly transparency reports.

- Introduce statutory obligations for platforms to inform users about takedowns or shadow bans.

- Establish a grievance redressed mechanism in consultation with journalist unions.

D. International Engagement

- Encourage the UN and regional bodies like SAARC to monitor and censure violations.

- Use diplomatic pressure from democratic states to protect Bangladeshi journalists in exile.

- Link foreign aid conditionality to media freedom benchmarks.

E. Media Literacy and Civil Society Mobilization

- Launch media literacy programs to educate citizens about disinformation and algorithmic bias.

- Fund independent journalist associations and digital security training.

- Support academic institutions in researching and archiving suppression data.

- Immediate Legal Reforms:

Repeal or amend vague clauses in the Cyber Security Act that allow arbitrary arrests and censorship.

- Institutional Safeguards:

Establish a Media Ombudsman under parliamentary oversight to review press complaints.

- Digital Platform Protection:

Form a national registry of journalist accounts to prevent algorithmic targeting and harassment.

- Journalist Protection Program:

Funded by national and international donors to provide legal and medical support for at-risk journalists.

- Civil Society Collaboration:

Promote alliances among media, academia, and civil rights organizations to resist coordinated repression.

The findings from took, when interpreted through democratic theory and algorithmic governance frameworks, confirm that Bangladesh is undergoing a transformation in its repression toolkit—from overt state violence to algorithmically obscured, legally justified suppression. This hybridization complicates both resistance and international accountability. Policy reforms must, therefore, operate on multiple levels: legal, institutional, digital, and civic. Only then can Bangladesh begin to restore press freedom and rebuild a deliberative public sphere essential to democratic life.

7. Conclusion

Bangladesh is witnessing an intensifying crisis in media freedom. The evidence from August 2024 to June 2025 illustrates a pattern of repression aligned with state interests, facilitated by legislative loopholes, digital technologies, and political patronage systems. A free press is a cornerstone of democratic governance, and its erosion threatens not just journalists, but the civic health of the nation.

7.1 Synthesis of Findings

This study has traced a detailed and systematic pathway through which press freedom in Bangladesh has been eroded between 4 August 2024 and 20 June 2025. The findings highlighted a dangerous convergence of legal repression, algorithmic governance, and extra-legal intimidation as means of silencing critical journalism. Whether through the extensive deployment of the Cyber Security Act (CSA) 2023, platform-level censorship enabled by opaque moderation systems, or direct intimidation by state and non-state actors, the empirical evidence points to an increasingly hostile environment for journalistic independence.

The study revealed 241 verifiable incidents of suppression, with legal and digital tactics replacing more overt physical violence. These transformations signify a shift toward subtler, yet equally potent, forms of authoritarian control—technocratic, legally framed, and often algorithmically executed.

7.2 Democratic Erosion and the Role of Law

The instrumental use of laws such as the CSA to target dissent undermines the very foundation of democratic pluralism. Rather than being a neutral safeguard for society, the legal system has been weaponized to chill speech, enforce silence, and maintain regime legitimacy. This legal authoritarianism redefines the boundaries of permissible discourse, resulting in a collapse of the normative role of the media in a democracy.

This erosion of press freedom, far from being an isolated aberration, should be understood within the framework of competitive authoritarianism or hybrid regimes, where elections are held and legal structures exist, but opposition and free speech are systematically undermined (Levitsky & Way, 2010).

7.3 The Algorithmic Frontier of Suppression

The study also shows that Bangladesh’s press repression is no longer confined to the analog world. Platform governance, driven by both state requests and algorithmic logics, now plays a central role in determining what news is seen, circulated, or silenced. Through shadow banning, content takedowns, and account suspensions, platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and X (formerly Twitter) have become central actors—either complicity or through structural design—in the architecture of suppression.

This finding invites a rethinking of digital sovereignty and global platform responsibility. While tech companies claim neutrality, their opaque content moderation frameworks and selective cooperation with state actors threaten the rights of users in fragile democracies.

7.4 Impact on Journalistic Integrity and Practice

The human cost of these repressive trends is borne by journalists who navigate a climate of fear, legal ambiguity, and constant surveillance. Field testimonies revealed widespread self-censorship, mental health struggles, and the adaptation of clandestine practices such as using VPNs, pseudonyms, and secure messaging apps.

Young and rural journalists, in particular, face heightened vulnerability due to lack of institutional support and legal awareness. Women journalists face gendered abuse that silences them from within, compounding the already oppressive external environment.

7.5 Limitations of the Study

While the study utilized a robust mixed-methods design, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, incident underreporting remains a challenge due to fear among journalists. Second, the role of informal state actors—e.g., party-affiliated goons, digital troll farms—was not systematically analyzed. Third, lack of transparency from platform providers (Meta, Google) limited our ability to fully map algorithmic suppression. Nonetheless, triangulation across data sources helped mitigate these constraints.

7.6 Future Research Directions

Given the fluid and evolving nature of media repression, future research should focus on:

- Longitudinal tracking of CSA-related legal cases

- Ethnographic studies of digital exile and transnational journalism

- Platform audit studies examining algorithmic opacity and bias

- Comparative studies across South Asia on regional patterns of digital authoritarianism

7.7 Final Polishes

Press freedom is not merely about the right to publish; it is about the right to question, expose, narrate, and dissent. The findings of this study confirm that Bangladesh is in the midst of a profound democratic crisis, where the tools of repression have modernized, and the guardians of truth—journalists—are increasingly besieged.

Restoring press freedom in such a context will require more than legal reform. It demands institutional courage, platform accountability, and civil society mobilization. It requires building new alliances—across borders, platforms, and ideologies—that reaffirm the journalist’s role not as an enemy of the state, but as a pillar of the public good.

Only through such a multi-pronged and persistent effort can Bangladesh hope to reclaim the democratic space necessary for truth to thrive.

References

Ahmed, N. (2021). Digital Authoritarianism in Bangladesh: Surveillance, Censorship and Control. South Asia Journal of Policy Studies, 14(2), 95–113.

Ahmed, N. (2023). Press freedom and state repression in South Asia: A comparative analysis. Dhaka University Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 67–89.

Ahmed, T. (2025). Post-DSA Bangladesh: Continuity of Surveillance under a New Name. Dhaka: Centre for Law and Media.

Amnesty International. (2025). Bangladesh: Journalists under Fire. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org

ASK (Ain o Salish Kendra). (2025). Human Rights Situation in Bangladesh: Annual Report. Dhaka: ASK.

Bermeo, N. (2016). On Democratic Backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 5–19.

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2017). Troops, trolls and troublemakers: A global inventory of organized social media manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute. https://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order. Oxford Internet Institute.

Chowdhury, A. I. (2013). Media and Political Transition in Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Affairs, 35(1), 67–89.

Chowdhury, F. (2022). Media, Politics and Control in South Asia. New Delhi: Routledge.

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2025). Attacks on the Press in 2025. New York: CPJ.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and Its Critics. Yale University Press.

Deibert, R. (2019). The Road to Digital Unfreedom: Three Painful Truths About Social Media. Journal of Democracy, 30(1), 25–39.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Diamond, L. (2002). Thinking about hybrid regimes. Journal of Democracy, 13(2), 21–35.

Dissanayake, S. (2019). Sri Lanka’s Press Under Pressure: Media Freedom in a Post-War State. South Asian Journal of Media Studies, 12(2), 23–44.

Dryzek, J. S. (2000). Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford University Press.

Feldstein, S. (2021). The Rise of Digital Repression: How Technology is Reshaping Power, Politics, and Resistance. Oxford University Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books.

Freedom House. (2023). Freedom in the World: Bangladesh Country Report. https://freedomhouse.org

Freedom House. (2024). Freedom in the World 2024: Bangladesh Country Report. https://www.freedomhouse.org

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. Yale University Press.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action: Reason and the Rationalization of Society (Vol. 1). Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. MIT Press.

Hasan, M. T. (2023). Lawfare and Democracy in South Asia: Bangladesh as a Case Study. Asian Legal Review, 19(1), 55–78.

Human Rights Watch. (2022). Bangladesh: Repeal or Reform Digital Security Act. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org

Human Rights Watch. (2024). Cybersecurity or Censorship? The New Face of Repression in Bangladesh. https://www.hrw.org

Human Rights Watch. (2025). Bangladesh: Escalating digital repression under CSA 2023.

Human Rights Watch. (2025). Digital Authoritarianism in Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org

Islam, K., & Sultana, S. (2023). Vulnerability of Regional Journalists in Bangladesh: A Neglected Frontier of Media Rights. Dhaka Journal of Media Studies, 11(2), 34–55.

Khan, M. S. (2024). The Cybersecurity Act: A Cloaked Sword. Bangladesh Journal of Law, 34(1), 25–49.

Khan, S. R. (2024). Cybersecurity or Censorship: The Rebranding of State Control in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Media Policy Forum.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Crown.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

Mehta, P. B. (2021). India’s Illiberal Turn: The Role of Media Capture. Indian Journal of Political Studies, 45(3), 78–102.

Moyn, S., & Sitaraman, G. (2017). The Lawfare Paradox. Harvard Law Review Forum, 130(1), 45–61.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Norris, P., & Odugbemi, S. (2010). Evaluating Media Performance. In Public Sentinel: News Media & Governance Reform (pp. 3–26). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Ottaway, M. (2003). Democracy Challenged: The Rise of Semi-Authoritarianism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF). (2025). World Press Freedom Index: Bangladesh. https://rsf.org/en/bangladesh

Reporters Without Borders. (2024). World Press Freedom Index: Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/bangladesh

Roy, S. (2020). Manufacturing Consent in Modi’s India: The Political Economy of Media Control. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(48), 18–25.

RSF (Reporters Without Borders). (2024). World Press Freedom Index – Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/bangladesh

Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. Yale University Press.

Sultana, R. (2023). Digital Panopticism and Self-Censorship in Bangladeshi Journalism. Dhaka Journal of Media and Culture, 11(2), 51–77.

Sweeney, M., & Fritz, N. (2020). Chilling Effects: The Psychological Impact of Surveillance and Censorship on Journalists. Journalism Studies, 21(7), 854–869.

Thakurta, P. P. (2022). Freedom Under Fire: Media, Money and Modi. New Delhi: Context.

Tilly, C. (2003). The Politics of Collective Violence. Cambridge University Press.

Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB). (2024). Curbing Corruption and Safeguarding Press Freedom. https://www.ti-bangladesh.org/

UN Human Rights Council. (2024). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents

Wiles, R., Crow, G., Heath, S., & Charles, V. (2008). The Management of Confidentiality and Anonymity in Social Research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 417–428.

Yusuf, H. (2020). Pakistan’s Muzzled Press: A Case of Military-Backed Media Control. Asia Media Report, 15(3), 88–110.

Zakaria, F. (2003). The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad. W.W. Norton.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

1) Dr. Akash Mazumder

1) P. K. Karker: Political Analyst and Research Fellow in South Asian Politics