More than five decades after the 1971 Liberation War, in which Pakistani forces and local collaborators were accused of committing genocide against Bengalis, the issue of accountability remains unresolved. Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, has faced renewed scrutiny for its alleged role in supporting Pakistani military operations, including the formation of auxiliary militias implicated in mass killings, rapes, and looting.

Following the dramatic political upheaval on August 5, 2024—when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled the country amid mass student-led protests, leading to the installation of an interim government under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus—Jamaat-e-Islami has experienced a significant resurgence. The party, previously banned under Hasina’s administration, saw restrictions lifted, allowing it to re-emerge as a key political player ahead of anticipated elections.

Students burn effigies of Pinaki, Elias for anti-liberation propaganda

Graves of five freedom fighters set on fire in Rajbari under Yunus’ watch

Yet, as Jamaat positions itself for greater influence, its leaders have issued vague, unconditional apologies for “any suffering” caused since 1947, carefully avoiding explicit acknowledgment of the party’s controversial actions during the 1971 war. Critics argue this strategy aims to rehabilitate the party’s image while evading direct responsibility—and potentially shielding Pakistan from demands for a formal apology.

The Shadow of 1971

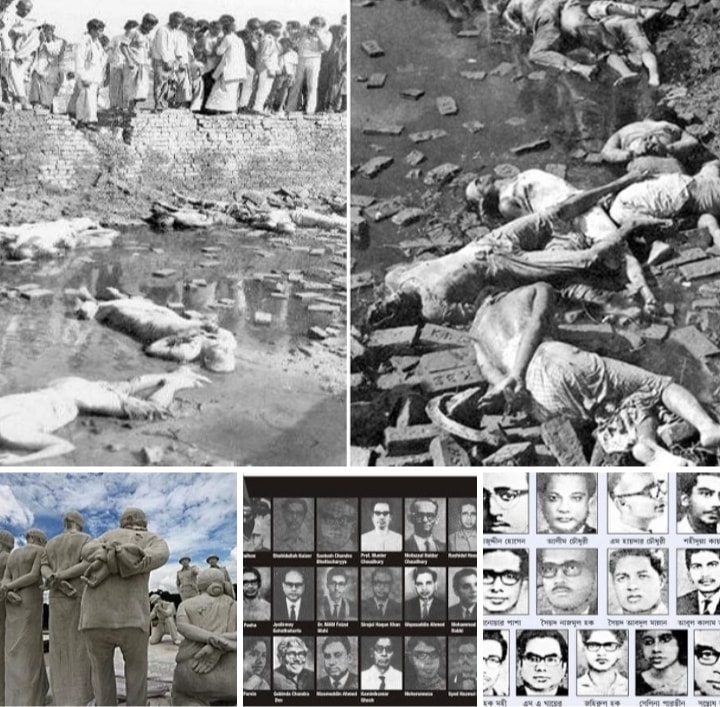

The 1971 war saw East Pakistan break away to form Bangladesh after a brutal crackdown by West Pakistani forces. Official Bangladeshi accounts estimate three million deaths and the rape of 200,000 women, with auxiliary forces like Al-Badr and Razakars—allegedly backed by Jamaat-e-Islami—playing a direct role in targeting intellectuals, freedom fighters, and civilians.

Jamaat leaders, including Ghulam Azam and Motiur Rahman Nizami, were later convicted in war crimes tribunals under Hasina’s government, though the party dismissed these as politically motivated. The party’s historical opposition to Bangladesh’s independence, rooted in its commitment to a united Islamic Pakistan, has long tainted its legitimacy.

Post-2024 Resurgence and Evasive Apologies

The August 2024 uprising, triggered by quota reform protests but escalating into anti-government demonstrations, toppled the Awami League government. Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman announced the formation of an interim government, marking a pivotal shift. Jamaat-e-Islami, whose student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir, actively participated in the protests, benefited immensely: bans were lifted, and the party regained legal status in 2025.

Amid this revival, Jamaat Ameer Shafiqur Rahman has repeatedly offered broad apologies. In May 2025, following the acquittal of a party leader in a war crimes case, he stated: “We, as a party, do not claim we are above mistakes. We seek an unconditional apology to everyone who has been harmed.”

In October 2025, speaking in New York, Rahman expanded: “From 1947 to this day, October 22, 2025… whoever has suffered any pain or harm because of us—we seek forgiveness unconditionally, whether from an individual or the entire nation.”

Analysts describe these statements as strategic ambiguity—expressing regret without specifying the 1971 atrocities or admitting culpability. Past leaders like Ghulam Azam offered similar vague “expressions of sorrow” in the 1990s, framing actions as “political mistakes” rather than crimes.

Warming Ties with Pakistan: A Shield for Historical Denial?

Parallel to Jamaat’s manoeuvres, Bangladesh-Pakistan relations have thawed dramatically under the Yunus interim government. High-level visits in 2025, including foreign secretary talks and ministerial meetings, focused on trade, defense cooperation, and direct flights.

Erasing the nation’s father: An assault on the 1971 Liberation War

RESET BUTTON: Yunus is replacing 1971 memorials with July monuments

Destruction of 1971 murals an example of Yunus’ pro-Pakistani agenda

Bangladesh raised demands for a formal apology for the 1971 atrocities and repayment of pre-partition assets (estimated at $4.3-4.5 billion). Pakistan expressed willingness to discuss but has historically claimed issues were “resolved” in past agreements (the 1974 tripartite deal and 2002 expressions of regret by Pervez Musharraf), rejecting genocide characterisations.

Critics suggest Jamaat’s influence in the post-2024 landscape indirectly bolsters Pakistan’s position by downplaying calls for accountability. As Jamaat eyes electoral gains—potentially splitting from former ally BNP and appealing to conservative voters—its evasive stance on 1971 aligns with Islamabad’s narrative.

Voices of Dissent and Calls for Reckoning

Political analysts and rights activists argue that without a specific, party-level apology acknowledging 1971 collaboration, Jamaat’s rehabilitation risks erasing history. “These are not apologies; they are attempts to polish the image amid criticism,” said one commentator.

As Bangladesh approaches elections, the debate intensifies: Can a party with such a legacy fully integrate without confronting its past? For many survivors and families of victims, vague regrets fall short of justice, while warming ties with Pakistan raise fears that historical truths may be sidelined for pragmatic gains.

The 1971 genocide remains a cornerstone of Bangladeshi identity. Whether Jamaat’s strategy succeeds—or forces a genuine reckoning—will shape the nation’s political future.

What does Grok know about Martyred Intellectuals Day?

On December 14, 1971, just two days before Pakistan’s surrender in the Bangladesh Liberation War, the Pakistani military and its local collaborators conducted a targeted operation to abduct and execute prominent Bengali intellectuals in Dhaka.

This massacre, known as the “killing of Bengali intellectuals,” aimed to deprive the soon-to-be-independent Bangladesh of its intellectual and professional leadership, including professors, journalists, doctors, artists, engineers, lawyers, and writers. Victims were rounded up from their homes, blindfolded, taken to execution sites such as Rayerbazar, Mirpur, Mohammadpur, Nakhalpara, and Rajarbagh, and killed by bayoneting, garroting, shooting, or other methods. Estimates suggest at least 125 to 300 intellectuals were murdered that day, part of a broader pattern where around 1,000 such professionals were killed throughout the war.

Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), an Islamist political party that opposed Bangladesh’s secession from Pakistan on ideological grounds—prioritising pan-Islamic unity over Bengali nationalism—played a significant role in these events through its affiliated paramilitary groups.

JI collaborated with the Pakistani regime by forming “peace committees” and raising armed volunteer forces, including the Razakars, Al-Shams, and particularly Al-Badr, which consisted of Bengali recruits trained by the Pakistani army. Al-Badr members were directly involved in identifying, arresting, and executing the intellectuals on December 14, based on pre-prepared lists allegedly created with Pakistani military input (such as names found in the diary of Major-General Rao Forman Ali).

These actions were part of JI’s broader support for Pakistan during the war, which included propaganda efforts and counterinsurgency against Bengali freedom fighters (Mukti Bahini). War crimes tribunals in Bangladesh later convicted several JI leaders, such as Motiur Rahman Nizami, of genocide, murder, and related atrocities tied to these events, leading to executions.

From JI’s perspective, the party maintains that it only supported Pakistan’s political unity in 1971—as did other groups—and denies direct involvement in crimes or genocidal acts.

1971: Pakistan’s guilt will not go away

Map of Misfortune: Asma Sultana’s ode to 1971’s legacy of resistance

They argue that allegations stem from politicised narratives, flawed tribunals with coerced testimonies, and exaggerated casualty figures (e.g., official claims of 3 million deaths contested by some scholars as 300,000–500,000, mostly from counterinsurgency rather than targeted ethnic killings).

JI calls for independent UN investigations into all 1971 crimes, regardless of perpetrators, and criticises the International Crimes Tribunal for lacking fair trial standards.

In October 2025, JI leader Dr. Shafiqur Rahman issued a vague, unconditional apology for any suffering caused by the party from 1947 onward, without specifying the 1971 atrocities or admitting guilt, framing it instead as a “wrong political decision.”

This has been viewed by critics as an electoral tactic ahead of the 2026 elections rather than genuine accountability.

Pakistan as a state has consistently denied committing genocide or war crimes in 1971.

The events of December 14 are commemorated annually in Bangladesh as Shaheed Buddhijibi Dibosh (Martyred Intellectuals Day), underscoring the lasting impact on national memory.

While mainstream historical accounts substantiate JI’s collaborative role in the massacre, reassessments emphasise geopolitical contexts (e.g., Cold War alliances with the US, Pakistan, and China against Soviet-backed India) and ideological motivations, urging a more nuanced view beyond binary “collaborator” labels.